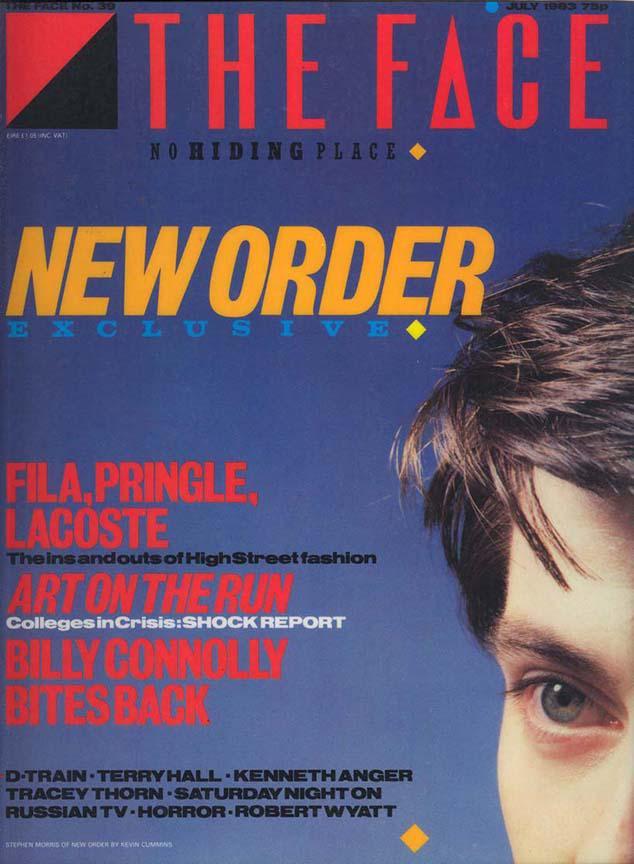

Since his days as a Manchester student photographer capturing hometown heroes Joy Division, The Fall, Happy Mondays, and The Stone Roses for publications such as the NME and The Face, Kevin Cummins has split the difference between art and journalism with an explosively real mise en scène that’s felt like “a landscape as to what the music sounded like,” in his estimation.

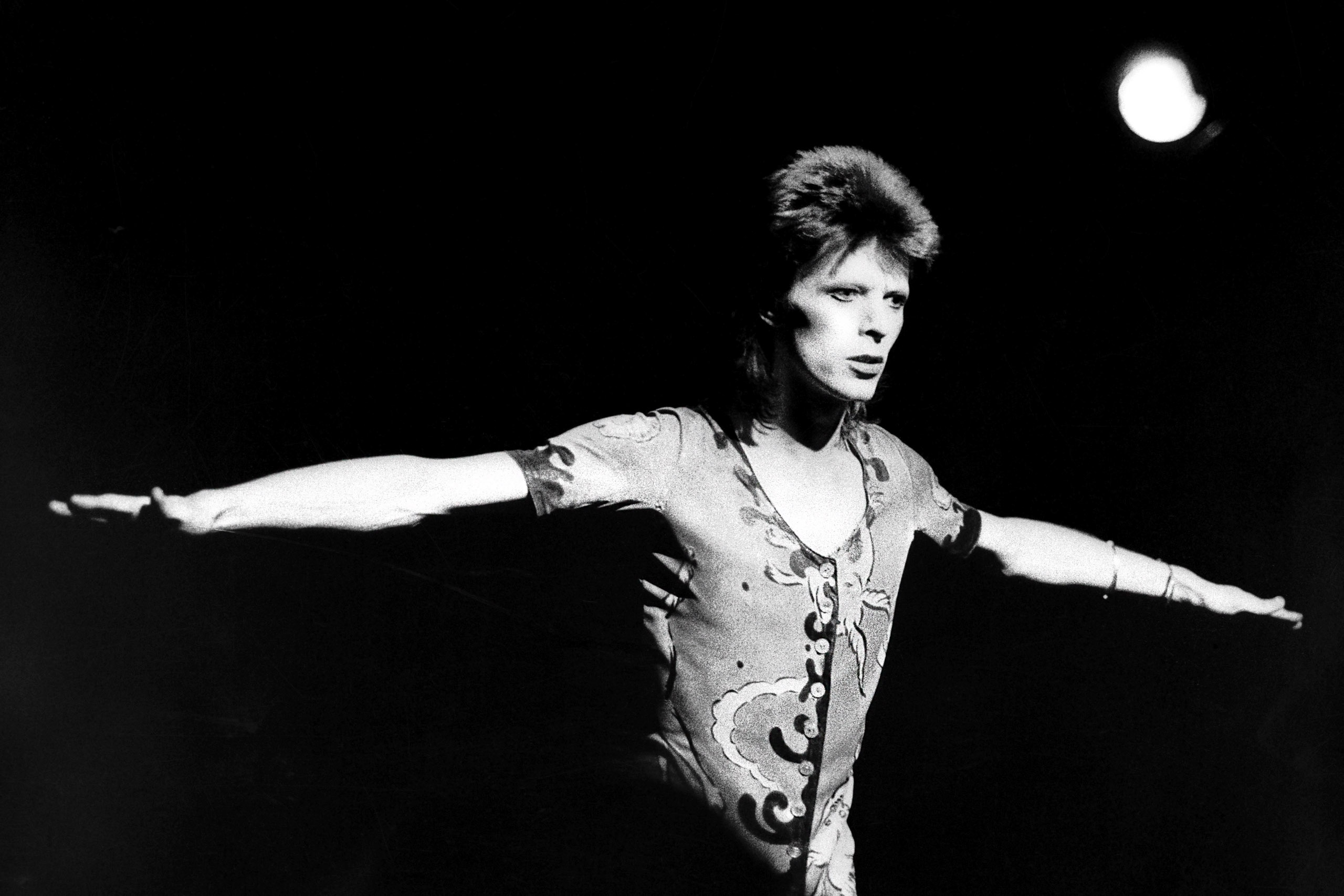

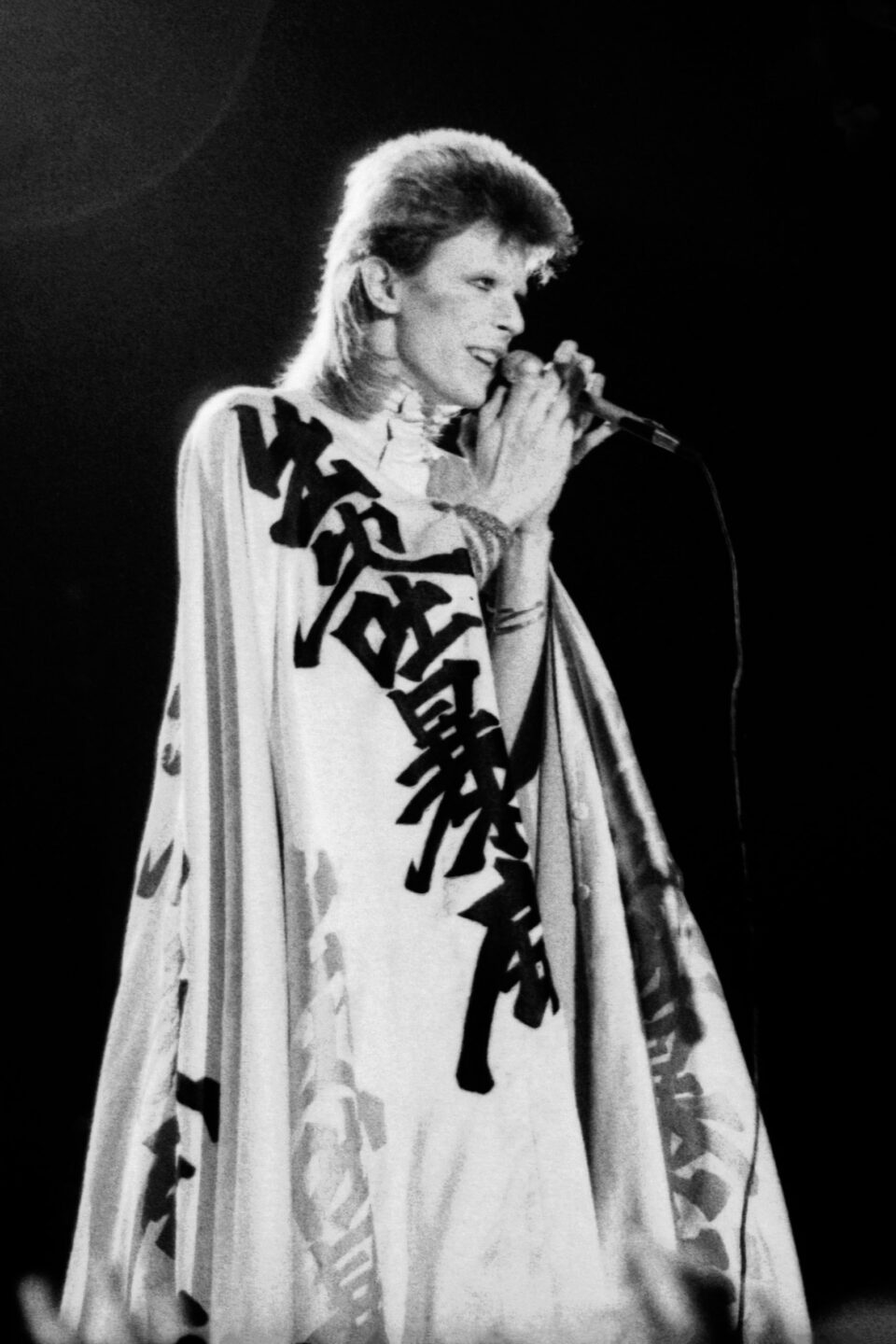

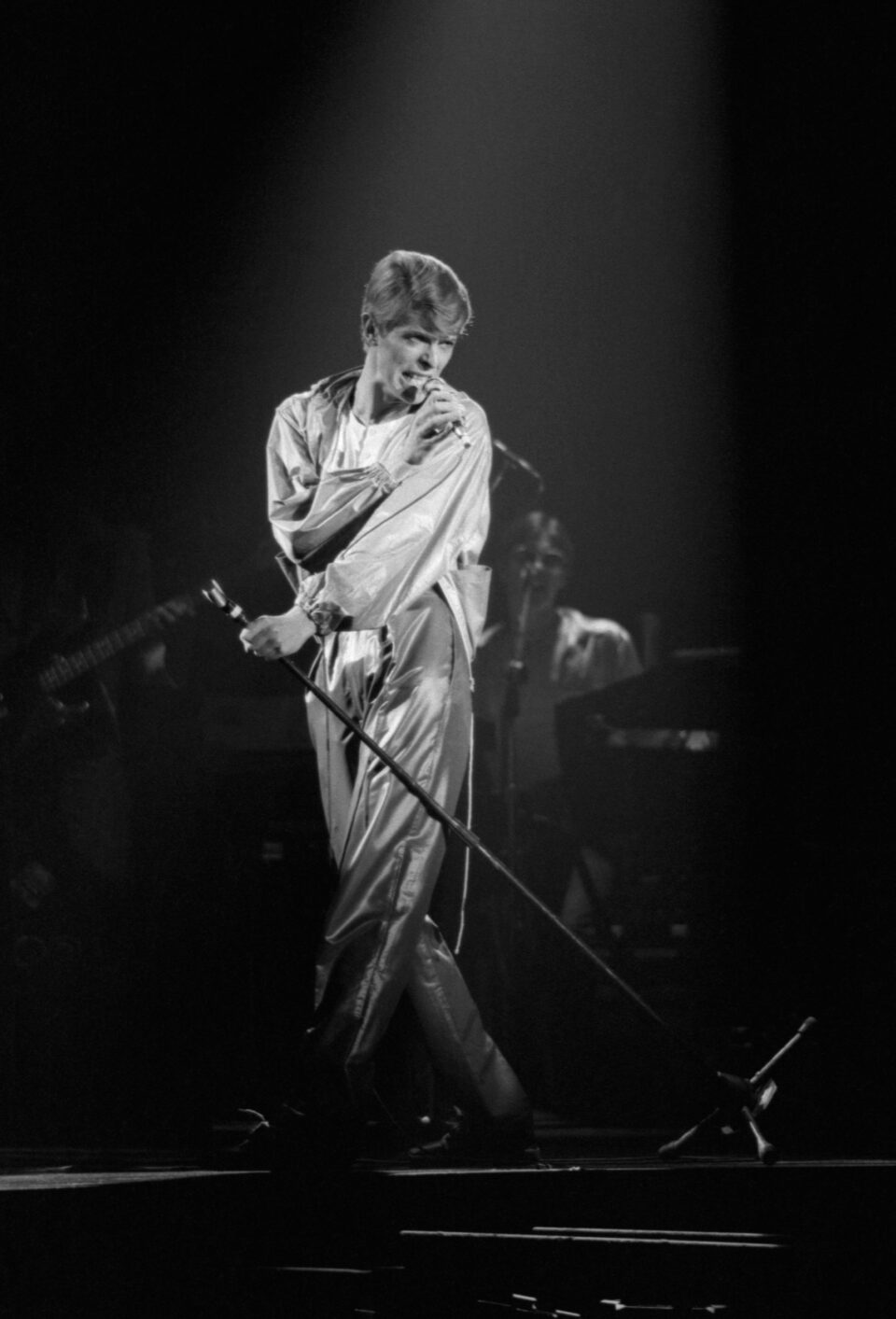

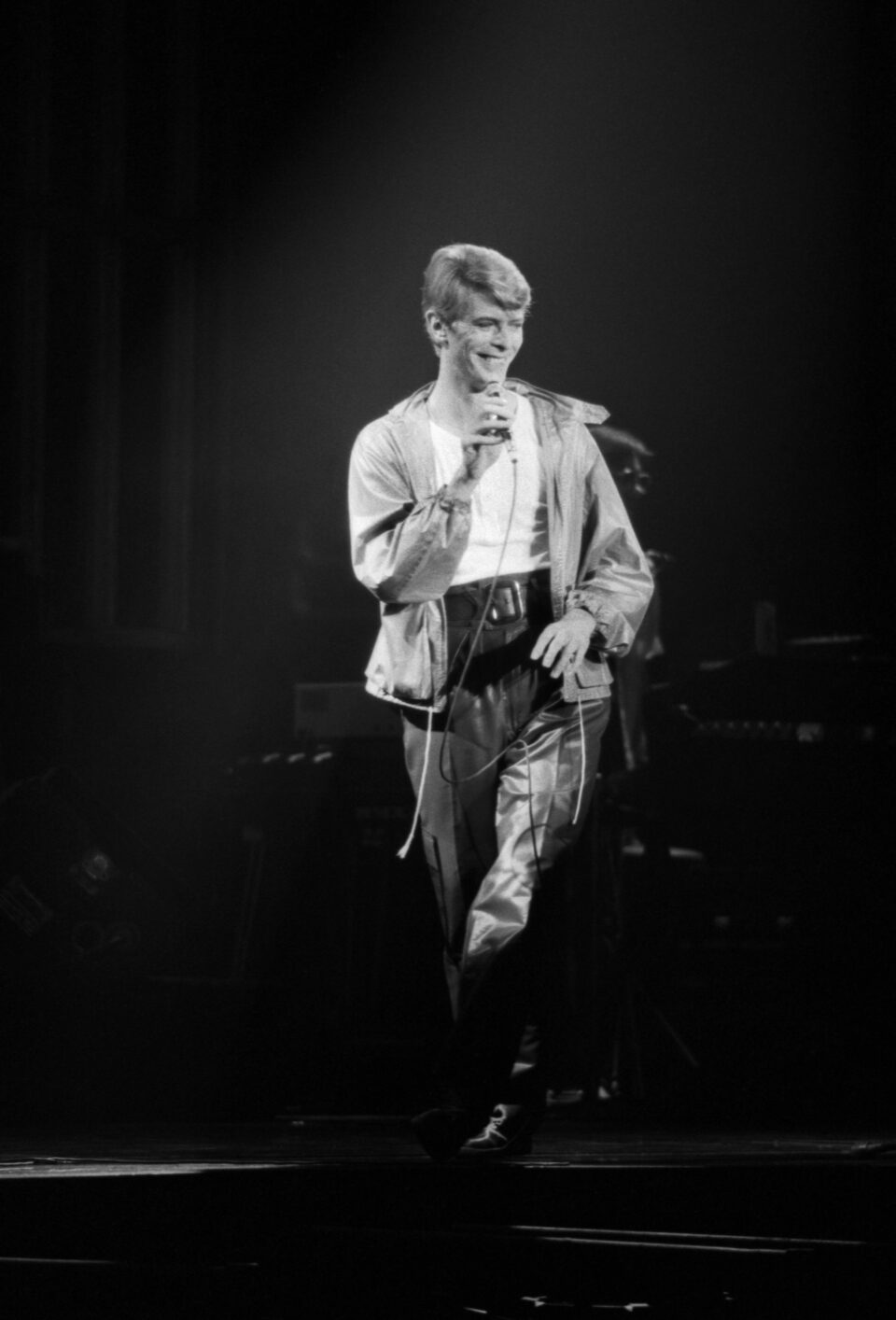

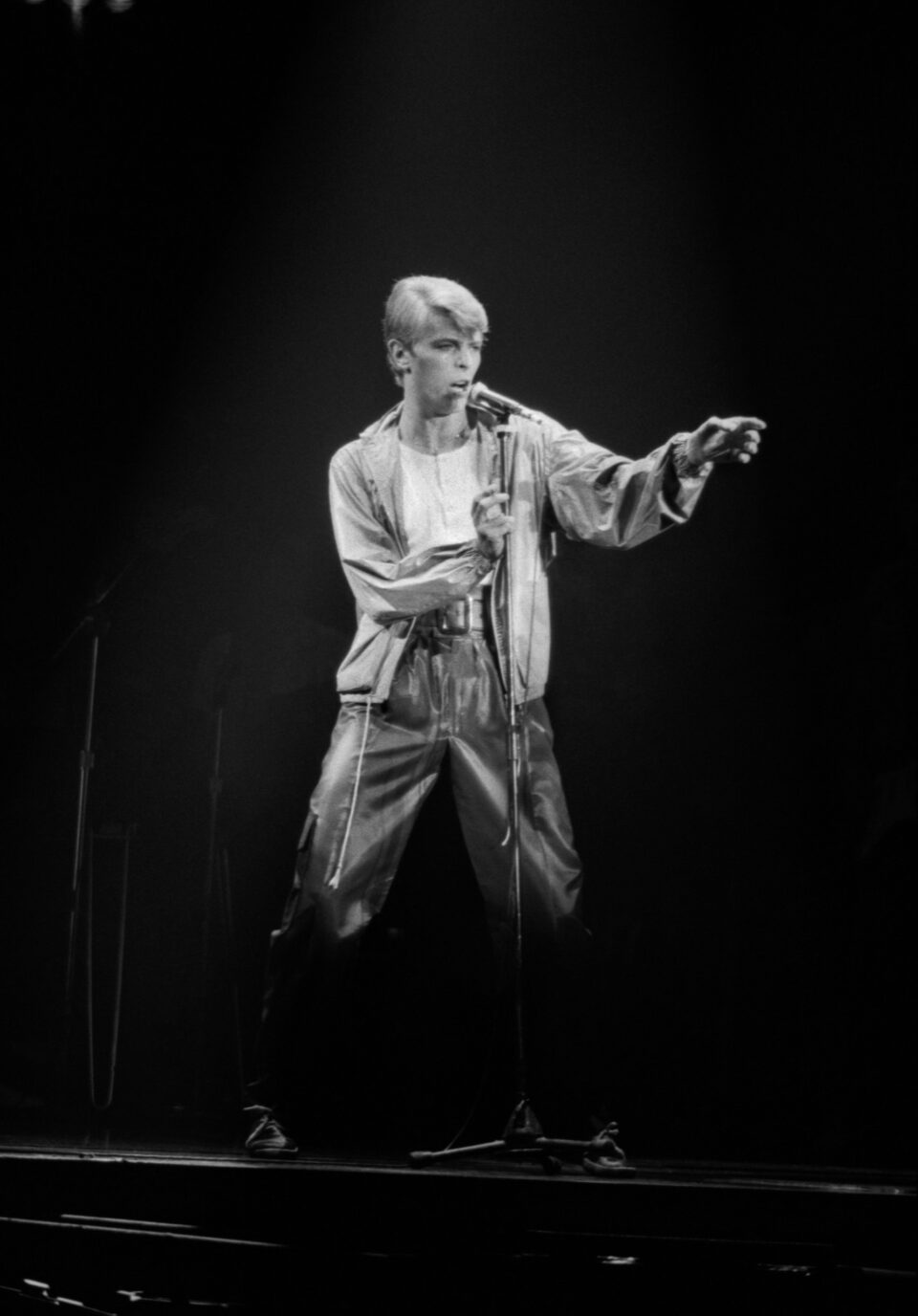

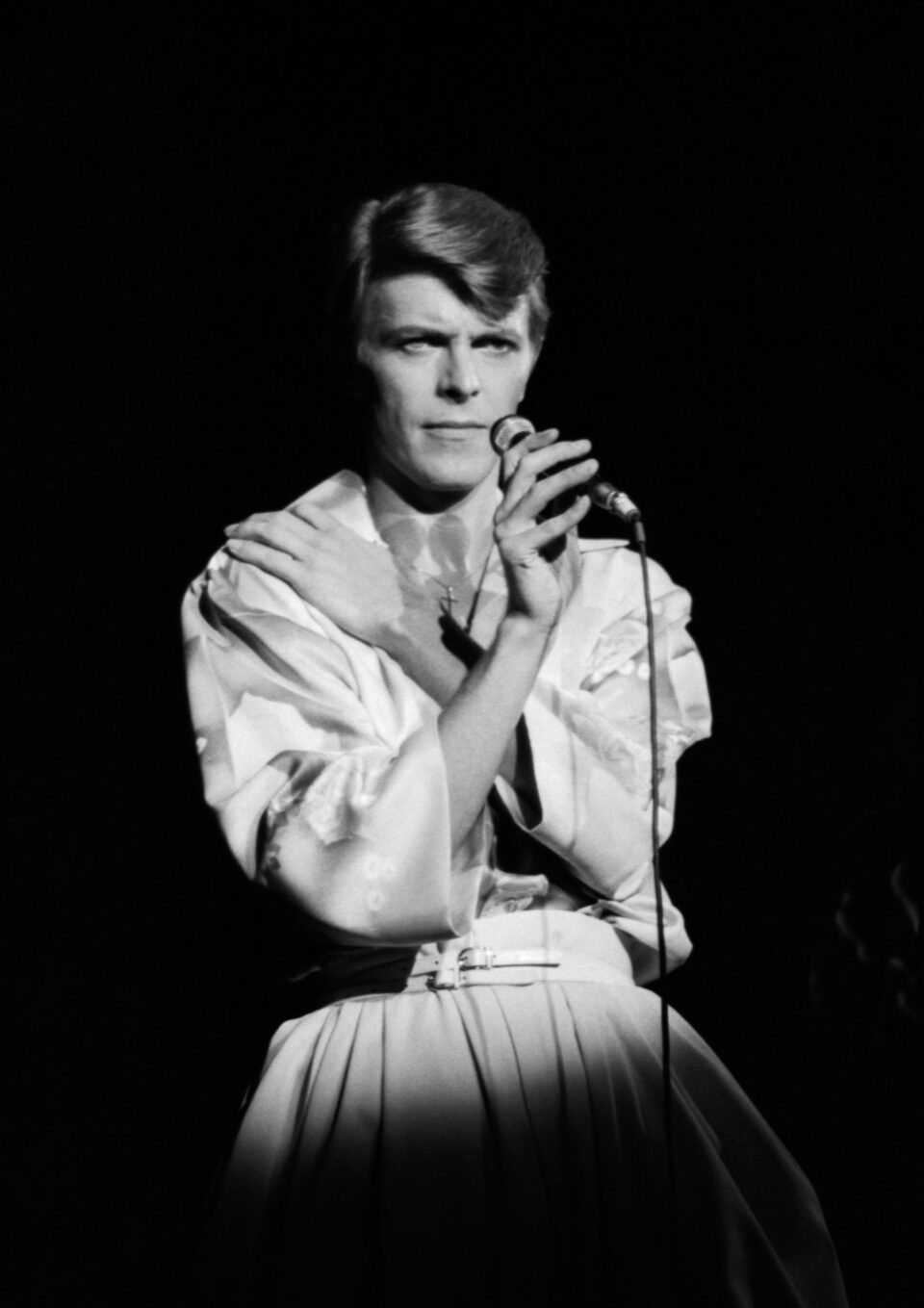

No artist, however, has been captured by Cummins quite like David Bowie has. A fan first, Cummins vividly snapped early Bowie-as-Ziggy concert photos before moving on to additional live Bowie personae such as the dramatic Thin White Duke, the sly blue-eyed soulman of Young Americans, and the golden-haired lad behind the Serious Moonlight tour. That love and longtime concert training prepared Cummins for solitary studio sessions with Bowie in 1991, 1995, and 1997—years when the singer sought new adventures in experimental music and collaborators such as those with Cummins in executing the visual side of those aesthetics.

With that comes Cummins’ theatrical new volume of music-based photography, David Bowie: Mixing Memory & Desire, and a July 9 live event moderated by LA-based photographer Piper Ferguson at Book Soup in West Hollywood. Before then, Cummins spoke with us from LA about all-things Bowie and beyond.

Your early years were spent capturing the most notable musical artists of Manchester. What can you say about that initial rush? How did it affect the future of your artform?

I graduated the year that punk started in Manchester, and I still couldn’t decide what area of photography I wanted to work in—if, indeed, I could get a job there. I went through four years of study in photography. Because I was already on-hand to document that scene, I thought it would be interesting, especially as I knew all the bands involved in the scene and we all went to each other’s gigs together.

A tight knit crew.

Yeah, a nucleus of around 50 people used to see virtually every show in Manchester. Once they started forming bands, I knew what I had to know as I had absolutely no interest in doing that. To this day I can’t play an instrument. I was just there to help further their career. And, by default, my own.

The other important element of your art is that you were there from the start as a founding contributor to The Face, the most crucial British/European publication of its time. What level of importance do you give The Face?

It was massively influential in the UK and, therefore, [also to] the hipper kids in America who were into the college radio scene and alternative culture. I know a lot of people in the United States would wait two months for their copies of The Face. We weren’t even earning enough on each copy, let alone being able to pay the postage.

“What I wanted was to create a landscape as to what the music sounded like. When I shot Joy Division early on, people looked at those photographs and believed that they knew what the band would sound like because of them.”

If I wasn’t in New York to get it when it arrived, I had to drive 100 miles into the city just to pick it up.

If you look at fashion magazines before The Face, everybody in the industry was still doing that 1970s Patrick Demarchelier look. Very formal stuff. The Face came along and blew that all apart. Similarly, that happened with the English music press.

Look, I hated rock photography when I was growing up. The only thing I did like was Annie Leibovitz’s study of The Rolling Stones and the tour they did. She came into it without a rock and roll background, and she documented that tour like it was important—establishment important. Most daily and weekly newspapers at that time didn’t cover rock in the UK—occasionally with Bowie—and it would usually be derogatory, always seen as juvenilia. Suddenly, there’s Leibovitz on tour with the Stones, and she’s documenting them as if they were heads of state, like she was on a presidential election tour.

That changed the game, removed it from cliché.

That coverage was important in how rock photography was seen. When I started, I absolutely hated that classic confrontational rock band photo—four lads in a band spraying beer into the camera lens. What I wanted, though, was to create a landscape as to what the music sounded like. When I shot Joy Division early on, that’s what I did. People looked at those photographs and believed that they knew what the band would sound like because of them.

I know that you worked for the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester when it opened, and now shoot regularly for the National Theatre in London. Did you change your look for theater, or did you change how we look at theater?

I think maybe when you look at Broadway or West End shots, most photos are staged for the photographer. In the 1960s, when film became faster to use, you could shoot productions while they were happening during dress rehearsal. That gave it more impact. When I was asked to shoot theater, I thought it was stiff and wanted to collaborate more with the director to make it exciting—prove that it’s worth $300 a ticket. So I would show how light was part of the production. I did the same thing with my live rock shots. Light helps to compose the image. That was what was there. I didn’t want to pretend that I’d just walked into someone’s sitting room. I wanted to capture the atmosphere of the play. I wanted you to understand that this was theater. There are a lot of egos to satisfy, and yours isn’t one of them. You’ve got to find the photograph who’s going to sell the show. You have to show that this play is exciting, that it has deeper meaning—not three and a half hours of thumb twiddling.

Would you say your work in theater photography makes you right for Bowie, especially your studio stuff with him?

I think so. I was very influenced by the way theater and dance was lit. Occasionally I’d bring a friend in from the theater to help me light something, or recommend how to give it dramatic impact. I’d often mix elements of formal portraiture into my studio shots. Something rock and roll, but an uneasy balance with that classical feel.

Such pragmatism, the balance of art and commerce, is where you’re at. You never forget that this is a journalistic pursuit, that you’re shooting for someone else.

I think so. Lots of people go into shooting rock and roll when they graduate school because they understand it, they grew up with it. I think the form has matured since I started. We’ve grown out of juvenilia. Also, you’re not shooting a gallery wall. You’re shooting photos that have to help to sell hundreds and thousands of papers—now web hits. Photographers would get frustrated because editors edited their photos or picked photos from what they would prefer. If you don’t want to be edited, shoot for a gallery wall.

Is there a thing to know about shooting Bowie, something that differs from any other artist?

The great difference for me is that I had photos of Bowie on all of my walls growing up. I didn’t have photos of a subject of mine such as Michael Stipe, because he was my contemporary. I was nervous shooting Bowie, even though I first captured him during Ziggy Stardust while I was still studying at age 18. When I had him in the studio for the first time I was terrified, because he was so otherworldly to me—and because when he came in to the studio he was wearing this terrible jacket.

“When I had Bowie in the studio for the first time I was terrified, because he was so otherworldly to me—and because when he came in to the studio he was wearing this terrible jacket.”

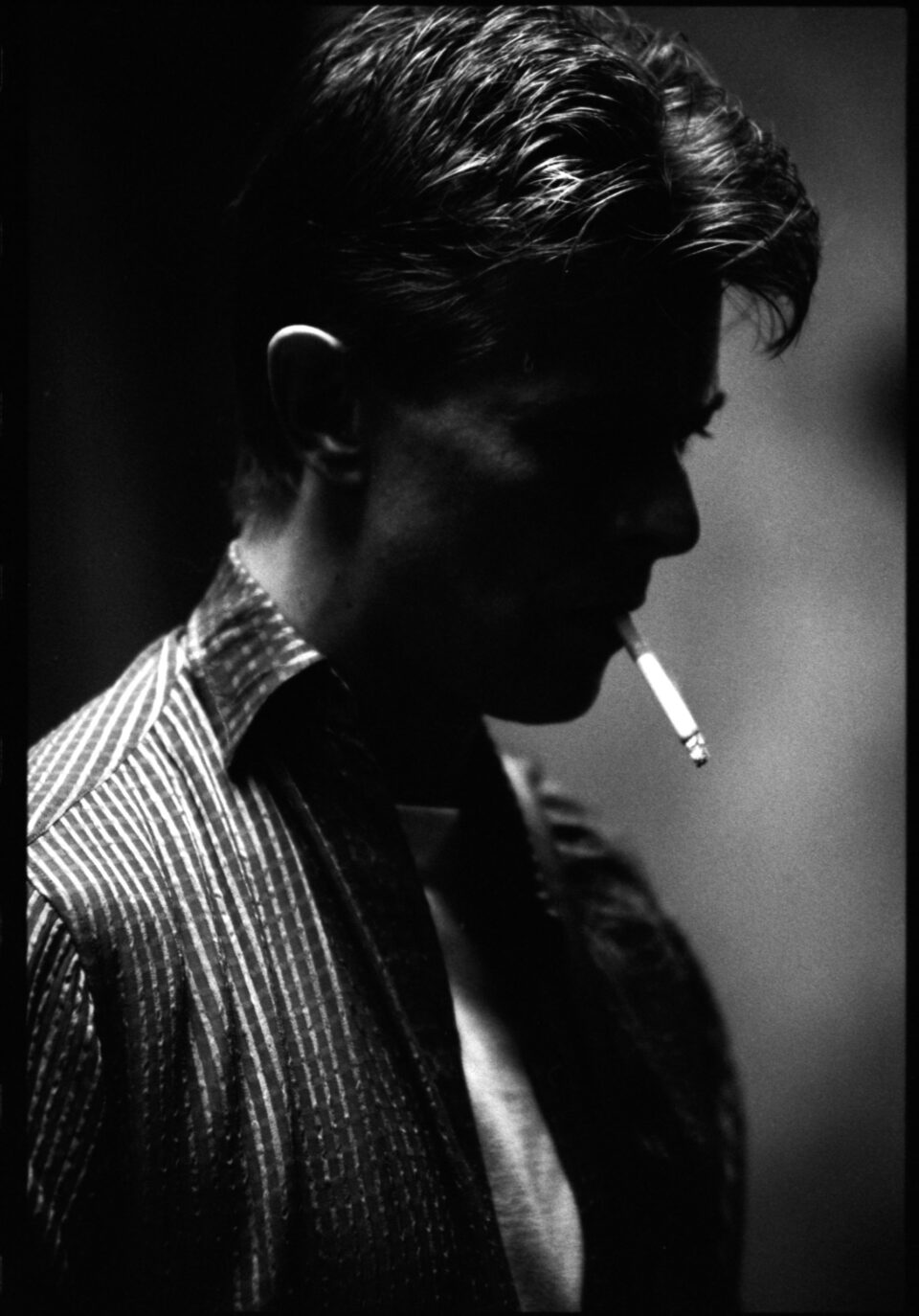

And I couldn’t ask him to take it off. He’s David Bowie, and I was completely awestruck by being there. And I had already been with and photographed everybody by that point—including Jagger. Yet with Bowie, I was hamstrung. I kept taking roll after roll of these pictures knowing full well that I couldn’t use any because of that jacket. They’re just terrible. After I shot him, however, I asked if I could watch him for a bit rehearsing with Tin Machine. More as a fan, almost. He said sure. He got changed into a plaid shirt and jeans, got more relaxed, and I was more relaxed. I took pictures of him, not knowing whether I was supposed to or not, and they were great. At one point he did look over at me with a raised eyebrow when he was standing on the drum riser. But he never stopped me from shooting. Those were the photos we used—more me, more Bowie, more relaxed. After that, I got more into the idea of working with him.

Why was he great to work with after those 1991 sessions?

Because, while being collaborative, he didn’t interfere. Quite often, musicians will interfere, even if they don’t know why they’re interfering. They don’t have that visual voice. They have an idea of how they should look, but they don’t have any clear ideas as to how to execute that. With Bowie, he absolutely knows. He gives you “Bowie,” but allows you to shoot him the way you want to do it without him getting involved. He let you be yourself, which is really interesting. Most musicians and actors have been photographed by everybody. It’s up to you to do something different, and they’ve got to allow you. These are my interpretations of David Bowie. I have to put my vision on this, or they might as well go into a photobooth.

“Bowie was difficult because he was one of the most photographed people on the planet. It’s like someone saying ‘Go take a new photo of the Empire State Building.’ Where do you start?”

Did you get the feeling that after that 1991 studio session, that he knew who you were and what you were about?

He did, actually. While that helped a bit, I’m not the type of person to ask for their email address or to stop around for lunch. I keep my professional distance. Some of the younger bands who know me and, say, my Stone Roses photos...they understand the medium. Some have no understanding at all, and are difficult to work with. Most, however, understand the industry and are into it.

When you were photographing him during the ’90s, this was a different Bowie from the 1970s and even the early ’80s. This was Bowie testing new waters again, experimenting with guitars, electronic music, industrial stuff. Does he let you in on who he is?

What I found interesting is that he was game for anything. He was relaxed enough to allow me to photograph him getting interviewed in 1995 before a session. He was great. He’d ignore me for most of the time, and look over when he was being asked one of the more ludicrous questions. That was good. Bowie was difficult because he was one of the most photographed people on the planet. It’s like someone saying “Go take a new photo of the Empire State Building.” Where do you start? What angle? How do you find an angle different from everyone else? You actually have to put all of that out of your head.

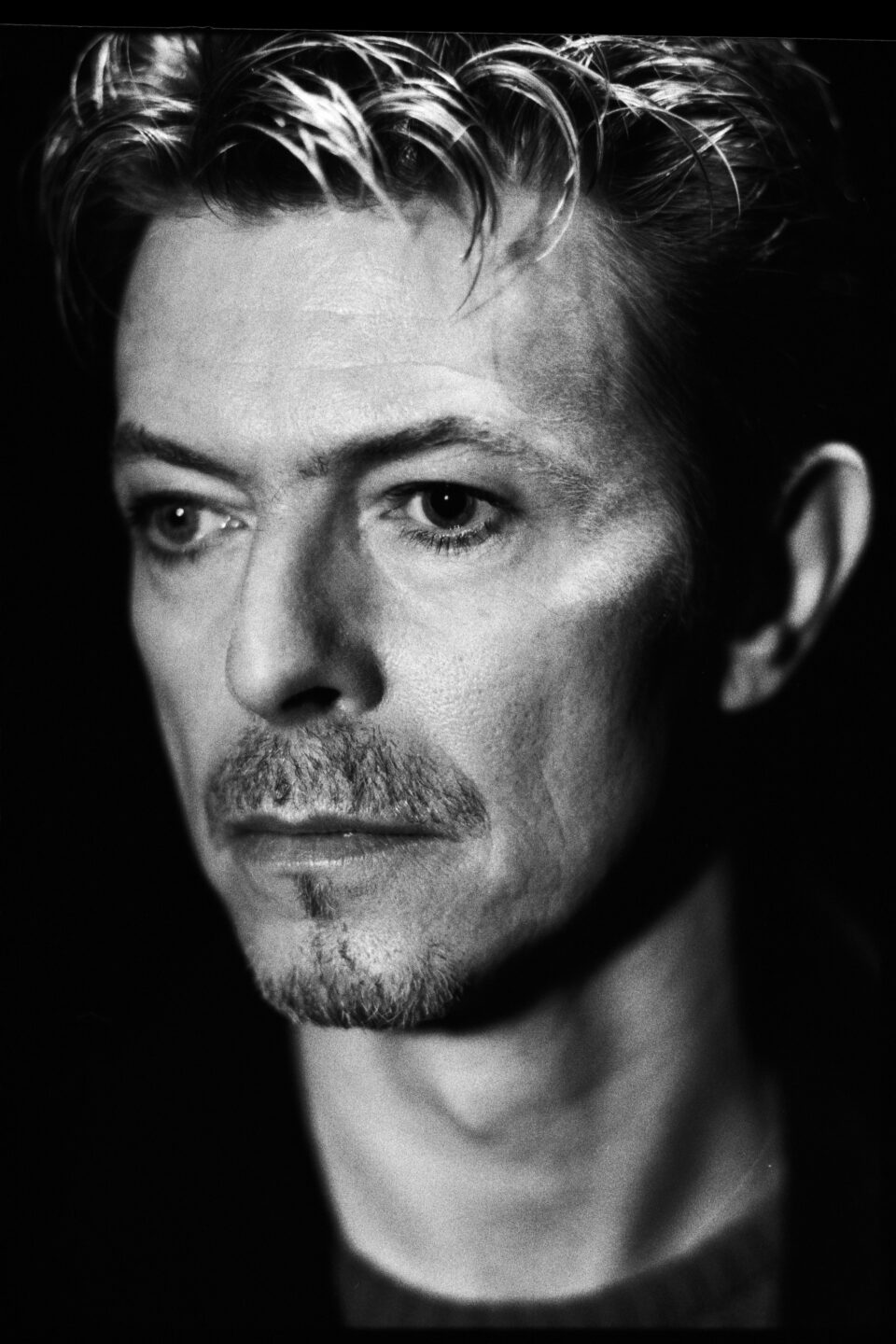

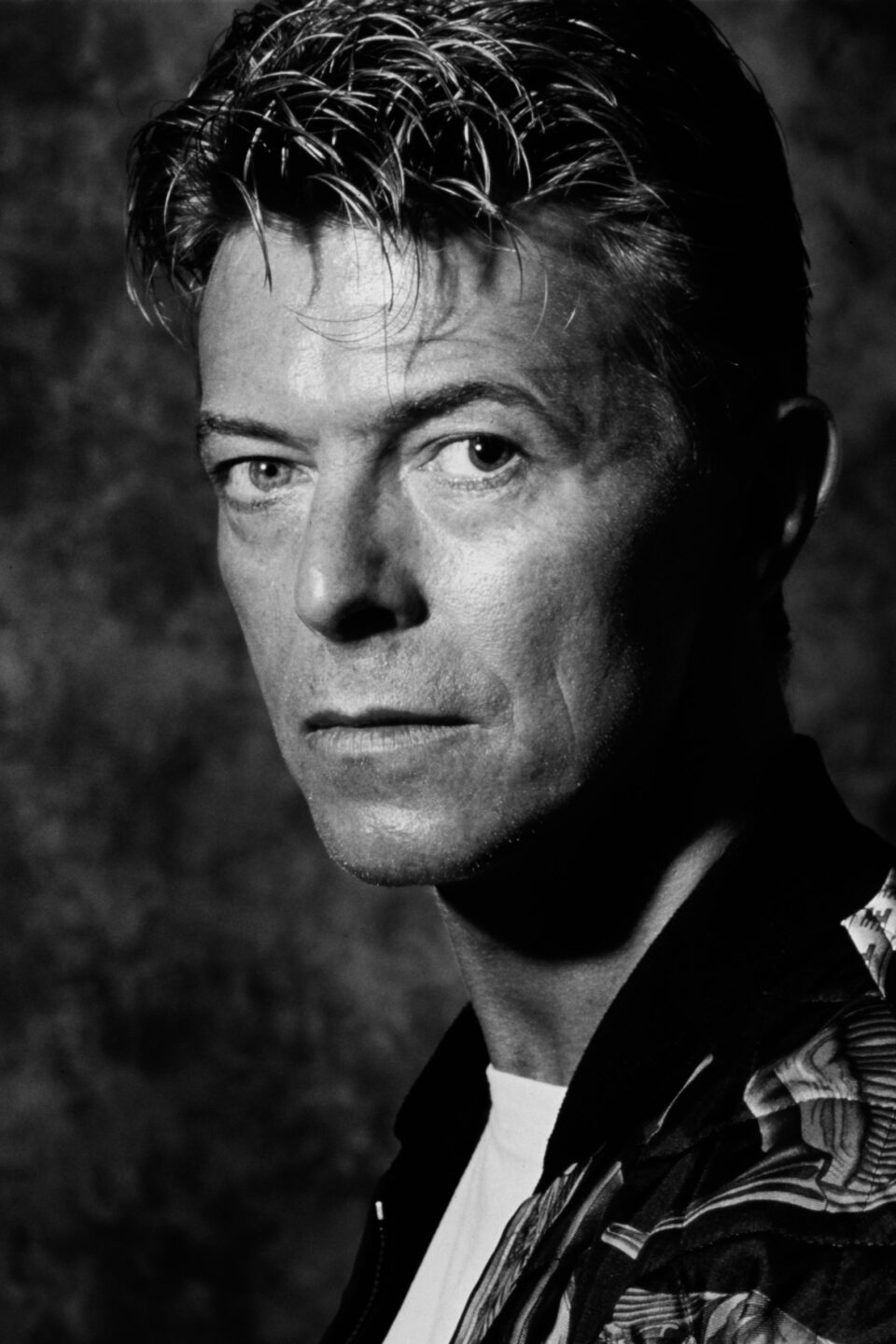

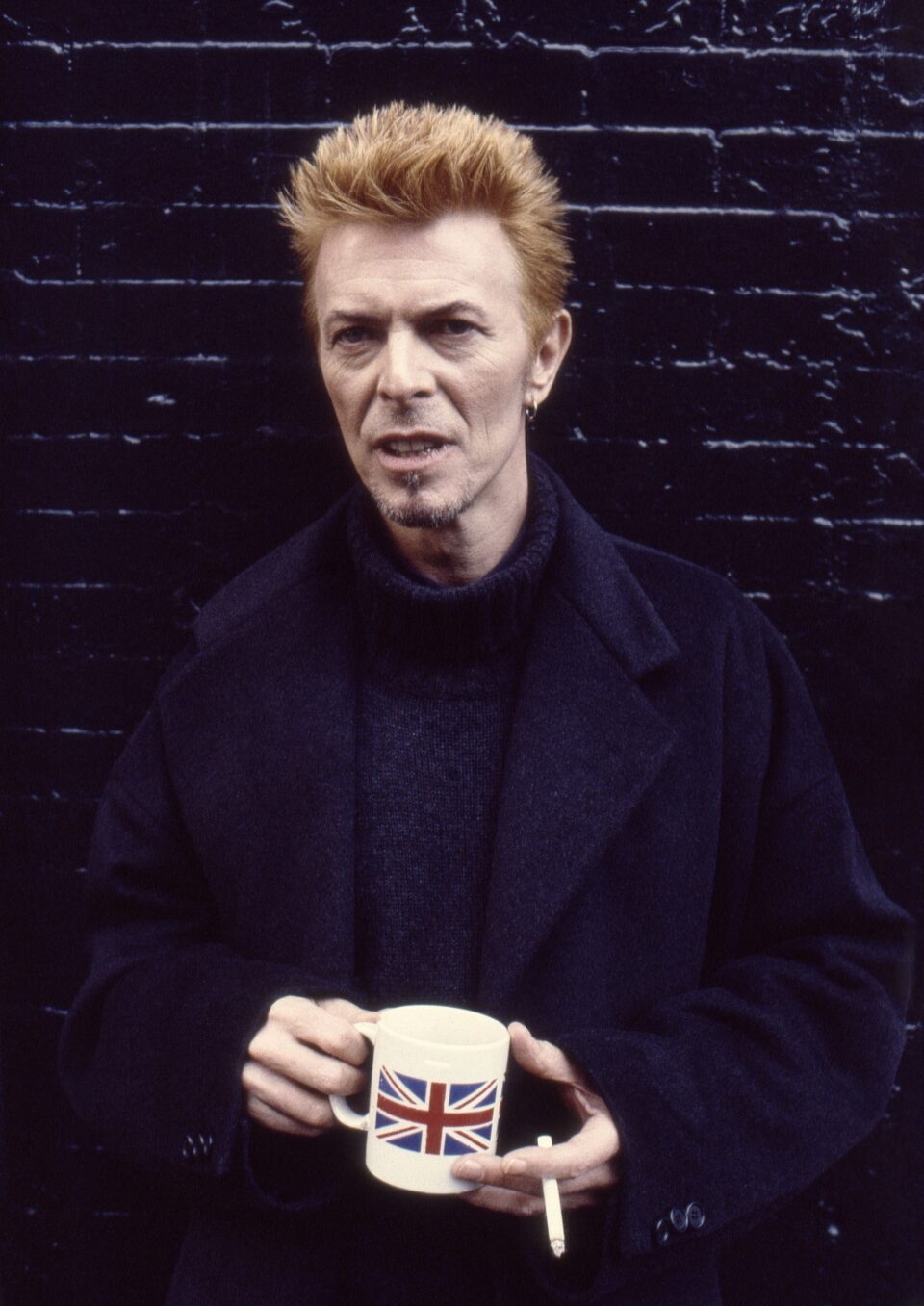

It's interesting you mention New York, because the last shots that you do with him are in 1997, in Manhattan—his city—and against a black brick wall and very close up. So stark.

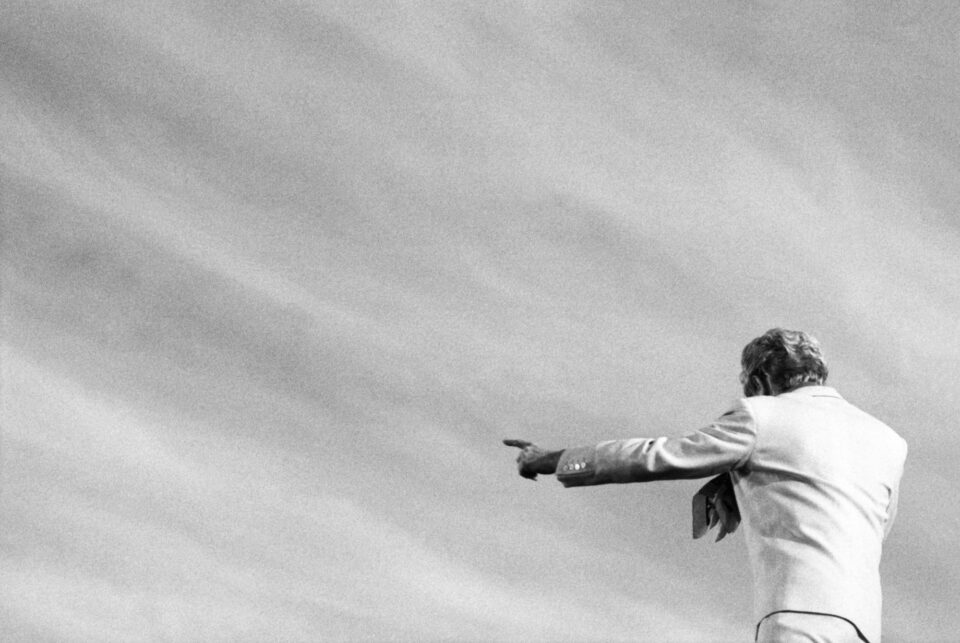

He wanted to meet at Tea & Sympathy, a British tea shop in the Village where he visited quite regularly. It was January, so it was quite dark. He wanted to do them inside, but I realized that there really was no light. He wasn’t going to tell me to go get lights, so I asked to go outside—that it wouldn’t take more than 10 minutes—and his only caveat was to bring his cup of tea with him. That’s what we did, especially since the cup had a Union Jack on it. Real Englishman in New York stuff.

He stood out in the street and no one walked past and said anything to him. Everyone now has phones, and no celebrity can move without getting snapped. But no one noticed or bothered him, and you could tell that he liked it. We ended up taking five rolls of film, spent 20 to 25 minutes working around. We went back into the tea shop and he asked me to get him another cup of tea because he was cold. He’d already suffered for my art long enough, so I bought him a tea, chatted for a bit, and that was it. FL