Cigarettes After Sex's Greg Gonzalez will also be taking over FLOOD FM for our “Hacked” series airing at 10 a.m., 1 p.m., 5 p.m., and 10 p.m. PST everyday from July 22 through 26 for a guest DJ takeover featuring hand-picked tunes and commentary. Mark your calendar and tune in here.

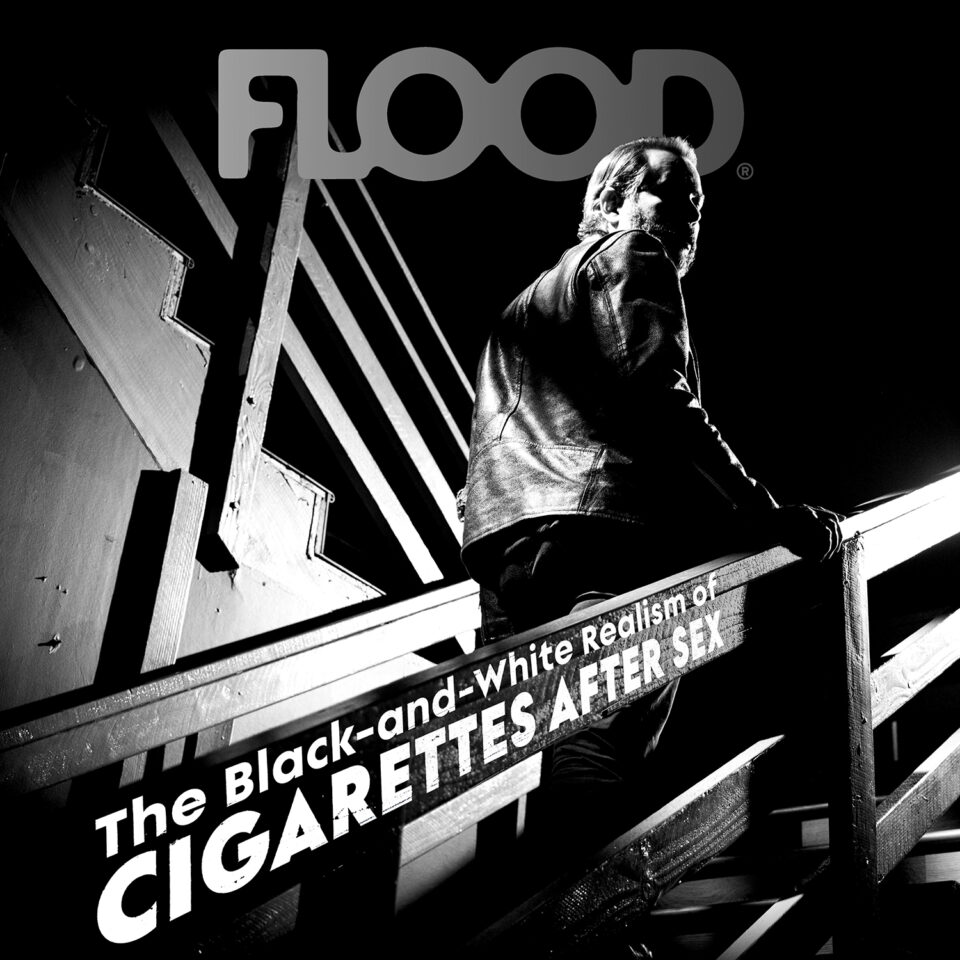

The man in black has come to the right place. Greg Gonzalez has just arrived at a gigantic studio space in Downtown Los Angeles, ready to represent his band Cigarettes After Sex on camera, and to pose in stark shades of black and white. On the floor is a spotlight blasting this humble bandleader in the face, projecting his shadow onto a white wall at least 20 feet high, and turning him into a kind of metaphysical figure from a German Expressionist movie.

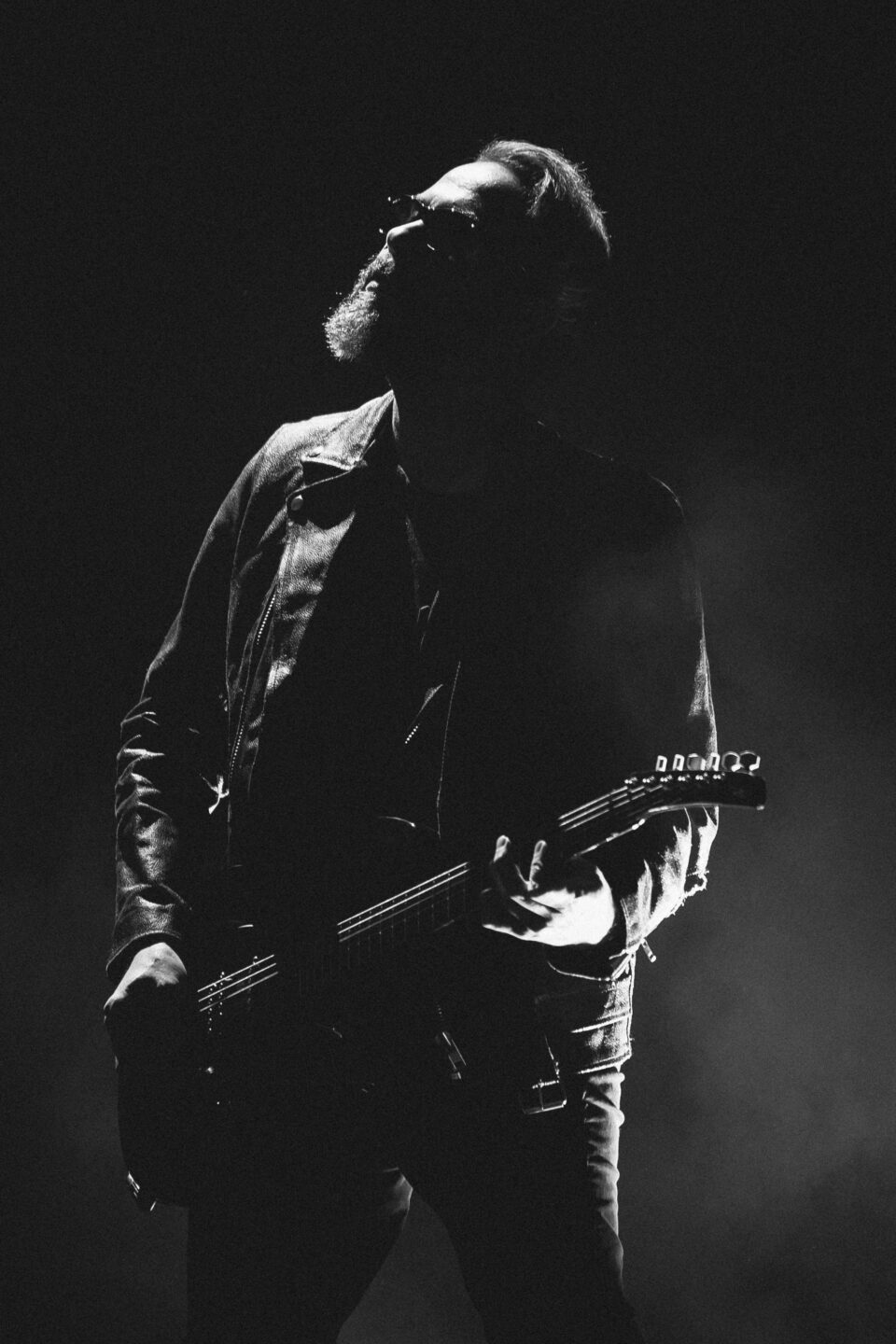

This is how he likes it. Black-and-white is not just an aesthetic, but a philosophy and a lifelong commitment to accompany Gonzalez’s songs of aching romance and gentle, smoky waves of melody. There are no official color pictures of Cigarettes After Sex, and there likely never will be—even concert photographers are asked to document their live shows in grayscale. It’s been that way ever since the band’s self-released debut EP over a decade ago, emblazoned with an alluring cover image: a 1929 photo by surrealist Man Ray of his lover’s bare neck in soft-focus. “I like the dreaminess of black and white. It takes you out of whatever you’re doing and it’s this other world,” Gonzalez explains. “It comes from those Man Ray photographs, which I love. It comes from old cinema—the Golden Age of Hollywood. It’s like French New Wave, it’s film noir. It’s all that stuff. It takes you out of reality.”

Photography: Kevin Kerslake Cover design: Jerome Curchod

Gaffer: Vincent Wrenn BTS/Video/Drone: Ryan Kane Fitzgerald BTS/Stills: Meg Meyer Special Thanks: Simon Thirlaway, Nina Miller, and Brigitte Guerra

It fits with the celestial sounds of Cigarettes After Sex, and in some ways it hardly matters how he’s photographed, since Gonzalez is a man who already exists in monochrome: black jeans and boots, black motorcycle jacket, and black beard all contrasting with pale skin. He’s pure that way, like Neo from The Matrix, Steve Jobs in his black turtlenecks, or Jeff Goldblum’s urban wiseacre in black leather being chased by a T-Rex in Jurassic Park. Gonzalez even once showed up on a cruise ship with his parents looking more goth than tourist on holiday (“I had to stick to my guns, you know?” he says with a laugh). As for his philosophy, Gonzalez likes to quote a favorite line from Wim Wenders’ 1982 film The State of Things (filmed in black and white, of course), spoken by a cigar-chewing Samuel Fuller: “Life’s in color, but black and white is more realistic.”

At the photo session, the huge studio space also represents something else: Cigarettes After Sex, a deeply romantic indie rock band originally from El Paso, Texas, has gotten used to being in big rooms. In 2024, Cigarettes After Sex are selling out arenas. And with a new album, X’s, showcasing ethereal music of growing sophistication around Gonzalez’s lyrics on love, sex, and romantic conflict, those shadows on the wall are likely to only grow bigger. The band’s international tour begins August 31 at the 21,000-capacity Bell Centre in Montreal, but the emotions remain human-scale. And Gonzalez feels it as much as anyone. “If someone’s crying in the front row, I usually can’t even look at them because it gets to me too much,” he says. “It feels like I can see their whole life on their face. I always have to look away.”

The band’s music is often understated but deeply felt, and has touched a nerve across multiple demographics and time zones. Even David Lynch, while praising the band’s 2017 song “Sweet,” has said the sound makes him feel “hopeful for the future.” This sound has evolved from its earliest form as uptempo synth-pop into something much darker, more Leonard Cohen than Madonna. “Life got darker, too,” he says. “There were too many breakups, too many romances—and worse things happened, too. It was a reflection of what I was going through.”

“I like the dreaminess of black and white. It takes you out of whatever you’re doing and it’s this other world.”

X’s is largely about a recent relationship that ended after three years, though the title song refers to a series of portraits of Marilyn Monroe shot by photographer Bert Stern in 1962. The actress famously drew thick red X’s over the slides she didn’t like, all of them later published in a book that Gonzalez and his lover once treasured together. “Honest with the love you give, careless with the way you talk,” Gonzalez sings on “X’s.” “Say you want it just like this, sweet how the words slip.”

Work on the new album began the year after releasing Cry in 2019. The arrival of COVID-19 was a big interruption, but Gonzalez was soon sketching out ideas and recording demos with bassist Randall Miller and drummer Jacob Tomsky for three months at the since-permanently shuttered Bootleg Theater in LA, which was otherwise closed during the pandemic. From those sessions, Gonzalez created drum loops of beats he liked, then brought the band up to a house above the Hollywood Bowl to finish the album. The record’s first single “Tejano Blue” mingled the traditional music of his West Texas hometown referenced in the song’s title with ethereal layers of sound inspired by the Cocteau Twins. His vocals are quietly blunt and romantic: “We wanted to fuck with real love / Wanted it sweet, so pure and warm / Never only sleeping over.”

The hard edge of some lyrics are an intentional contrast with the soft sound of the music, Gonzalez says. “It’s meant to be pure passion. You’re saying something really intense to somebody, but it’s whispered. The feeling should be so intense that it makes you want to go do something. You can’t just talk it out. No, you have to have to sing about it. I have to write a melody about it. I have to write lyrics about it. I have to record it, put it out into the world. The emotion demands that it actually exists in the world in some way. It’s crystallized.”

“It’s meant to be pure passion. The feeling should be so intense that it makes you want to go do something. You can’t just talk it out. No, you have to have to sing about it.”

Several days after the downtown photoshoot, Gonzalez is in the downstairs bar of the Sunset Tower hotel. It’s about 85 degrees outside, and billboards of Eddie Murphy as Axel Foley are visible up and down the Sunset Strip. His choice of summer attire is the same as always: black.

Behind the art deco bar is a guy with dreads tied into a ponytail, shaking his mixed drinks to order to the same recognizable beat every time, as a barely audible soundtrack of jazz and light R&B plays overhead. This meeting spot was convenient to Gonzalez’s current place in the canyons, and he traveled here in an Uber with a driver miraculously playing ’80s Leonard Cohen on the stereo. “Most Ubers I get into, it’s just random Weather Channel and EDM or something,” he says with a laugh. He settles into a salmon-colored booth with an iced-tea, sipping from a metal straw.

His Uber driver is a perfect example of the larger music audience out in the world that isn’t focused solely on pop, hip-hop, and dance music. The audience of Cigarettes After Sex is like that, embracing a timeless romantic vibe that’s built upon layers of emotion, utterly detached from the passing musical trends of the moment. It helps to explain the massive crowds filling up arenas for a band which has yet to enjoy a traditional radio hit. Their successes are the result of enthusiastic word-of-mouth.

The band got its first taste of hysteria during tours in Europe and Asia after the music began to blow up on YouTube in 2015. That following year was the first real tour by Cigarettes After Sex, and they were booked into small rooms overseas that were unexpectedly sold out. “That’s where it felt really crazy, where there were small shows and we would get there and there’s people crying in the streets because they can’t get in,” Gonzalez recalls, peeking over his Ray-Bans. “And then the show would be like, we couldn’t hear ourselves. It was just pandemonium. It was really fun. That was the way to do it.”

He could never be sure about the future, but he’d always dreamt things could turn out this way—much like Elvis or Neil Diamond could play deeply romantic songs in arenas and have ladies running up onstage to steal a kiss or tossing roses and garments at them. “Trust me, I’d played enough dead gigs,” he says, looking around the mostly empty bar. “In my hometown gigs, it’d be like this right now: me playing and there’s no one in here paying attention. So it was cool to get that, finally.” Even if being an indie rock band didn’t seem the obvious path to that kind of attention, Gonzalez says, “I thought it should happen, ideally, in a perfect world. I was wishing for it. It’s supposed to be universal. It’s supposed to be like these big bands that I loved as a kid.”

Growing up in El Paso, Gonzalez was a teenage metalhead who listened to Slayer and Metallica before embracing the death-metal extremes of Cannibal Corpse and Carcass. That was also the sound of his first band, a group of pre-teens who played instrumental metal under the grim name Mortuary. Gonzalez had a goth-metal girlfriend, and they went out to see White Zombie together. “I would watch Metallica videos and see they were playing big, huge stadiums and think, ‘Yeah, someday I wanna do that. That’s the way to do it,’” he says now, making a connection between his youth and the current arena shows of Cigarettes After Sex. “So it feels like that’s a lot of the bedrock for whatever we’re doing now.”

“[As a teenager] I would watch Metallica videos and see they were playing big, huge stadiums and think, ‘Yeah, someday I wanna do that.”

Gonzalez speaks in quiet, almost gravelly tones, which might suggest a potential singing voice closer to the growling ’70s loverman Barry White. But in Cigarettes After Sex, his voice is often mistaken for a woman’s, which wasn’t exactly his intention. His aim isn’t androgyny, but total intimacy. “I was surprised by that,” he says with a laugh. “I’m not singing really high. It’s like a whisper. I’m just singing so quiet that it sounds really light.” He compares his approach to Jim Morrison crooning the understated Doors track “Crystal Ship.” Yet his greatest inspiration might be Françoise Hardy, an elegant French yé-yé hitmaker who died last month at the age of 80. “That’s the most beautiful sound,” he says. “I was like, ‘OK, that’s exactly the way I want to sing on records.’” There were many other inspirations for his approach: Chet Baker and Julee Cruise, Mazzy Star and the Cowboy Junkies’ 1988 album classic The Trinity Session. “All the stuff I used for influences for Cigarettes were really clear. That’s what my spirit is, really.”

Cigarettes After Sex is a memorable name, but it’s caused problems from the beginning. Many labels hated it, and even now it’s censored in certain conservative countries in Asia and the Middle East. “It’s a loaded name, but it seems like that gave us so much identity,” Gonzalez says. Ironically, he’s only a casual smoker (he’s smoked Dunhill Reds ever since seeing The Beatles do the same in the Get Back documentary), and it takes him a solid month to get through a pack. He insists the name is important, as it reflects a common, real moment in the human experience: “You’re with somebody, are intimate with them, the world slows down. And you smoke with them. And it’s like this one moment where the universe stands still for a second. And it’s so hard to ever get that in life, [since] everything’s so frantic. You’re in this cosmic zone for, if you’re lucky, 10 minutes. And then it’s like, alright, back to life now.”

Gonzalez left El Paso for Brooklyn in 2013, deciding that he had to move away to grow as a player and songwriter, to find a city with a scene big enough to have music agents, record labels, and entertainment lawyers. The first label to express an interest was 4AD, which was a miraculous event for Gonzalez, who’d worshiped their roster of artists like Cocteau Twins, Red House Painters, This Mortal Coil, and Scott Walker. “I was like, ‘Oh, holy fuck, 4AD?’” he says, but it was not to be. The label didn’t like the band’s name, and had ideas for changing what Gonzalez had created. “They were very nice and everything, but they wanted to change a bunch of stuff, too, and that was a bad sign to me,” he recalls of the discussions. “They’re like, ‘We’ll bring in other artists to work on the record covers and producers.” He’d hear these things repeatedly at other labels. “You don’t want to get into bed with somebody who’s already saying, ‘Let’s change this and change that.’”

“You don’t want to get into bed with somebody who’s already saying, ‘Let’s change this and change that.’”

Once the band started catching on, Gonzalez figured he didn’t have to change a thing, and ultimately chose Partisan Records, current home to PJ Harvey, IDLES, and Blondshell. Partisan released the band’s eponymous debut studio album in 2017 and offered some important guidance. They were the first to hear real possibility in the song “Apocalypse,” which the band leader wasn’t even sure he wanted on the album at all. It then caught fire on TikTok and has been one of the band’s most popular songs ever since. “You leapt from crumbling bridges / Watching cityscapes turn to dust,” Gonzalez sings on the single. “Got the music in you, baby / Tell me why / You’ve been locked in here forever / And you just can’t say goodbye.” The song was another tune with roots in his own life. “It felt like I was telling the story of my hometown, in a way. I couldn’t get out of there,” he says of the song, noting the influence Leonard Cohen’s 1966 novel Beautiful Losers had on its writing. The lyrics were about “girls I knew in my hometown. They were amazing. And they couldn’t leave. They were stuck in El Paso and some of them still haven’t left. I was singing to them.”

Beyond Cigarettes After Sex, Gonzalez also has aspirations to try filmmaking, to probe deeper into his existing cinematic obsessions. So far he’s made some short film vignettes, with plans to work his way to something bigger. Years ago he had an idea to work with Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin, the director of black-and-white cult classics such as The Saddest Music in the World and My Winnipeg who’s known for using archaic film techniques to tell modern surrealist stories. The concept was to collaborate with Maddin on some weird images that would be cut into an hour-long film and shown in a theater, where Cigarettes After Sex would perform a live movie score. The idea didn’t get too far beyond an initial discussion with Maddin, but Gonzalez still likes the concept. “He’s great, but I don’t think he was that into the project,” he says of the director, then adds with a smile, “I would still do it. The ideas I like are the ones that just hang around forever, and that one’s never gone away.”

“I really want to try directing, but I know that could take awhile. I want to do it the same way I did Cigarettes—totally [from] the ground up.”

It seems strange, then, that music videos haven’t factored into the band’s world at all. While he dreams of taking his noir visions to the big screen as a filmmaker, Gonzalez refuses to have a music video created for the band. “I really want to try directing, but I know that could take awhile. I might not do it ’til I’m, like, 50 or something because I know I’ll have to study. I want to do it the same way I did Cigarettes—totally [from] the ground up.”

While the release of X’s is still fresh, the bandleader is already planning the next album. He’ll take the band into a real studio for the first time, he says. Between tour dates, he’ll travel to Toronto for a week of sessions where he’ll write a song a day with the aim being to create music spontaneously, like a classic jazz album. “I kind of need that contrast: Now that I’ve spent four years on a record, I need to do something just kind of tossed-off,” he says with a smile. “If you can get that lightning bolt [of inspiration], it’s pretty amazing. It might take a few days to get into that mode. We’ll play a bunch of stuff, then we’ll try some more out nowhere stuff and see what happens.

“I haven’t written a thing for it.” FL