Once feared as thieves in the temple within the economy of the music business (“home taping is killing music” was the industry’s rallying cry in 1982), cassette tapes have proven themselves to be durable and democratic symbols of how one expresses themselves, artfully, affordably, and emotionally. Musicians who couldn’t afford pricey vinyl or CD pressings early in their career have forever gone the way of the cassette tape—in particular, early punks, avant-garde artists, and rappers-producers. When good (or bad) taste and romantic (and not-so-romantic) messages couldn’t be conveyed through mere words, what better way to say “I love you” than with a shareable homemade cassette mix that had a pre-planned obsolescence based on how many times it gets played? Without placing myself too far into another writer’s story, I have a deep abiding sense of pride in knowing that mixtapes I shared years ago are still in the valued possession of many a friend and foe who’ve told me so.

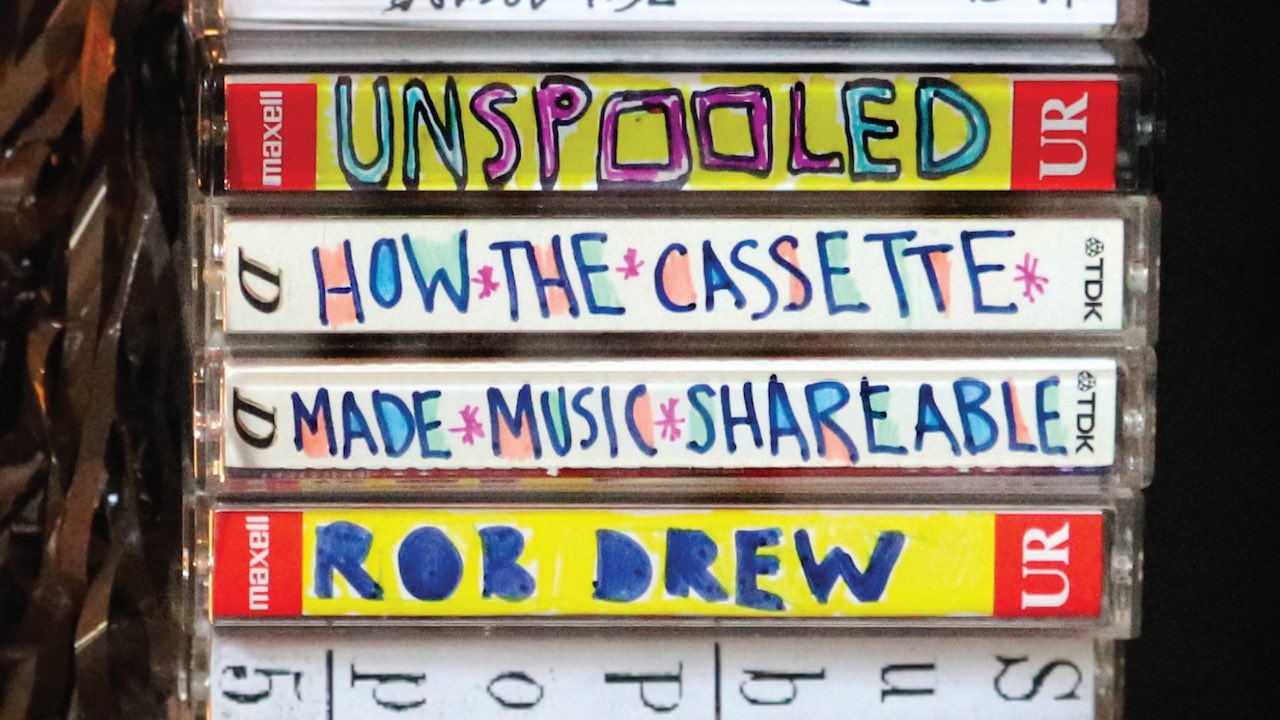

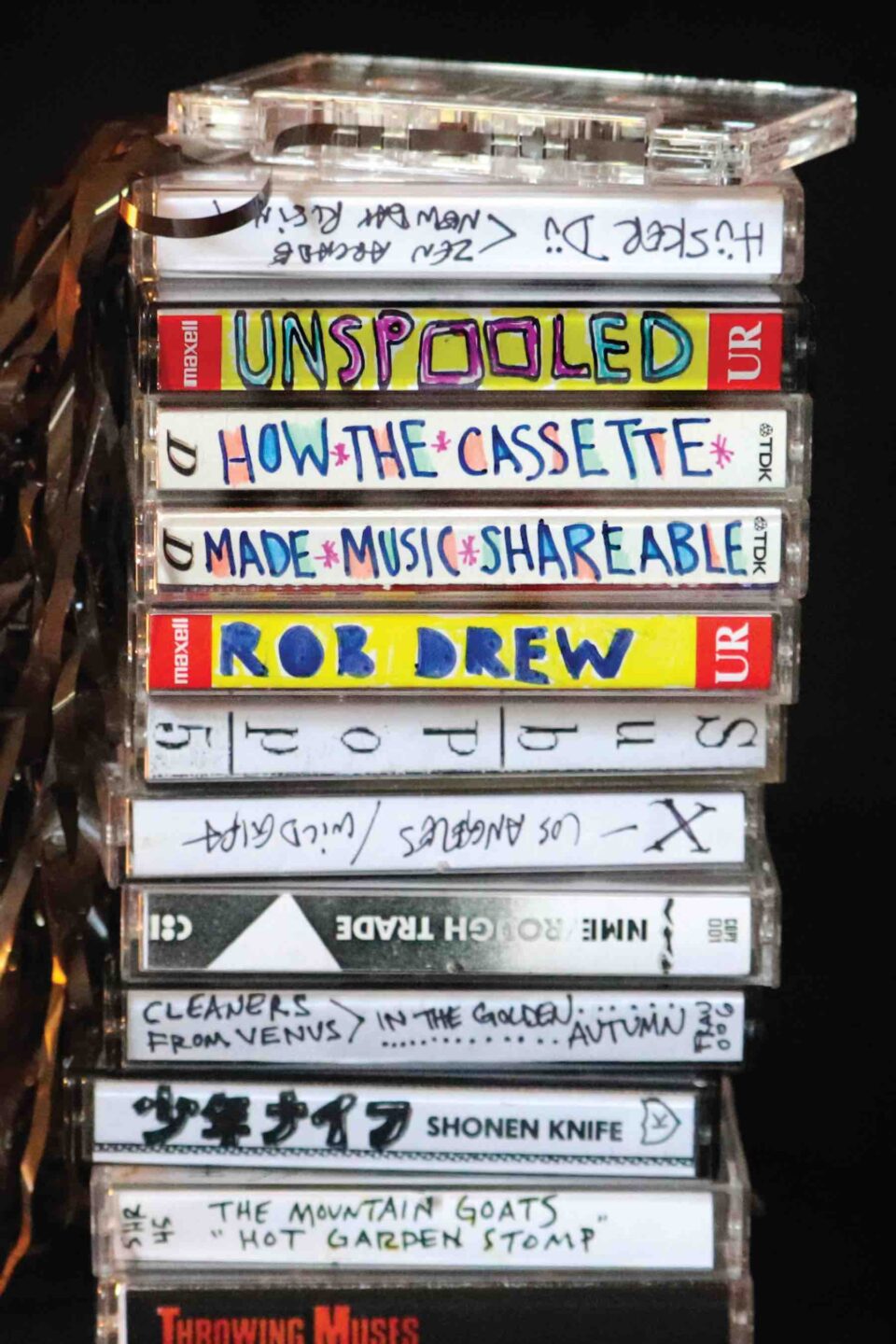

Scholarly author and Saginaw Valley State University Professor of Communications Rob Drew knows where you’re coming from if cassette tape is your go-to mode of recording, releasing, and sharing music. Just as his Karaoke Nights: An Ethnographic Rhapsody peeked deeply into the subtlest, most personal aspects of the culture of self-generated stardom, Drew’s recently published Unspooled: How the Cassette Made Music Shareable pulls out the stops—or the tabs, if you’re a real cassette fanatic—on the history, mystery, and marvel of the tape.

There’s much to be said of the pop phenomena connecting the art of cassette music-making/-sharing and karaoke entertaining in Drew’s mission. “I’ve always been interested in the interface between sound and music technologies and people, whether they’re listeners or musician-singers,” says the author. “Karaoke and the cassette are cases where technologies were deployed in everyday life. People could’ve chosen to deal with each differently, but chose to use these sound technologies to communicate, democratically, the idea of disintermediation. They took out the middle men, the gatekeepers, in pursuit of their aims.” With karaoke, suddenly, you could be the star—or at least share in certain rituals of exclusion and inclusion that looked like celebrity. With cassettes, anyone could record anything, quickly and cheaply.

If you chose to go further and record your band, your raps, or your solo artistry—like early DIY art-rock artists such as R. Stevie Moore and Eugene Chadbourne—you could make and release your cassette to order (“You didn’t need minimum pressings of 1,000 copies to start,” notes Drew) and publicize it in like-mindedly independent zines, then blogs, and now social media. “Tapes had a much faster turnaround time than vinyl or CDs,” says Drew. “Cassette is a very flexible medium, a true precursor to the phenomenon of Bandcamp and Soundcloud, where you can put your music up on the internet as soon as you finish it.” For cassette cultural history buffs, Drew also cites staples of the Pacific Northwest music scene—including OP Magazine, KAOS radio at Evergreen State College, K Records, and Sub Pop—as avatars of the tape, all of whom wind their way into Unspooled.

“Cassette is a very flexible medium, a true precursor to the phenomenon of Bandcamp and Soundcloud, where you can put your music up on the internet as soon as you finish it.”

At the very moment that hip-hop came to the fore, and Metallica began its thrash-metal reign—both through inexpensive tape sales and sharing—the record industry demonized the cassette and signaled its piracy as a plague on the record business, just as labels (and, ironically, Metallica) later went after Napster for its capturing their profits. “With cassette tape, the conventions of gatekeeping are gone,” says Drew. “My fascination comes with people suddenly having the opportunity to have a public voice, a musical voice, where previously that was unattainable to them.”

While one side of Unspooled discusses cassette-only artistry and labels—from rockers to rappers—the other side of Drew’s book looks at the romanticism (and ease) of communication that became the personal and very human mixtape. Like Cyrano parsing his desire for Roxane through the romantic goals of his less articulate pal Christian de Neuvillette, a mixtape could be used as the ultimate love letter or poison-penned missive. It could be used as a status symbol of great and singular taste on the side of the deliverer. It could be used to turn on those without the ears or means to know so.

“With cassette tape, the conventions of gatekeeping are gone. My fascination comes with people suddenly having the opportunity to have a public voice, a musical voice”.

It’s this latter side of the book that’s perhaps most important to Drew, as he’s been at this slow-boiling book project for nearly 30 years. “The resurgence that you see now in bands making cassettes, and cassette-only labels—in some cultures, the cassette tape never went away,” he says. “Home taping, and the sharing that went with it, was more modest and more appropriate than what file sharing and streaming became,” states Drew, conjuring images of Mission: Impossible’s smoking, melting tape. “That’s very possibly due to the fact that, with every ‘play,’ there was a loss of quality with each generation. You wanted that perfect version, because tape would slowly disintegrate. Once digital came along for good, you never had the worry of degeneration.”

As for his level of communication when it comes to mixtape-making, Drew laughs about coming late to the game. “I made my first mixtape at the age of 25, and came at it from a personal and scholarly standpoint. No, I didn’t court my wife through mixtapes. And yeah, I was definitely a little bit showoff-y. It was called ‘Sounds of the City Circa ’72’—even though I made it in 1986—and it was all songs I remembered from my youth: The O’Jays, Curtis Mayfield, The Chi-Lites, Sly and the Family Stone. Frankly, they weren’t deep cuts, but rather stuff that was readily available in the early ’70s. I just wanted to show off my appreciation for R&B music at a time when that music wasn’t being played on the radio. I wanted to show off my good taste.”

And that’s just what Unspooled does: smartly shows off Rob Drew’s level of good taste. FL