The idea of a “cult band” has always been a strange one, where a dedicatedly off-center yet indefinably charming act has a following dear and deep enough to border on the worrisomely obsessive—one hanging on every “iconic” word and rousingly original chord change, yet not exactly deep or large enough to make the object of their affection particularly wealthy. Those who worship at the mystical jangle-pop altar of New Zealand’s The Chills always got more than they bargained for, even when the band’s frontman Martin Phillipps was at his saddest (a plus for any insatiable cult member).

Ask anyone who joined the teen ranks of Pavement, Yo La Tengo, The Shins, and, most famously, R.E.M. after hearing 1982’s Chills-featuring Dunedin Double split EP, or the band’s 1987 debut LP Brave Words: one listen to Phillipps’ windy, wondrous brand of ringing psychedelia and you’re hooked. One taste of Phillipps’ warbling voice and sharply observational yet still dreamily absurd and wounded lyrics and you’re caught in the eye of his hurricane of hurt. Like Rodgers and Hart’s 1936 musical romp “Glad to Be Unhappy,” you could often sense Phillipps’ zeal through his distress. And, like what Eno once said about the hundred people who initially bought The Velvet Underground & Nico each having started cult bands of their own, the 200 people who bought Brave Words began bands that held sway while actually managing to make money, as was the case of Stipe & Co.

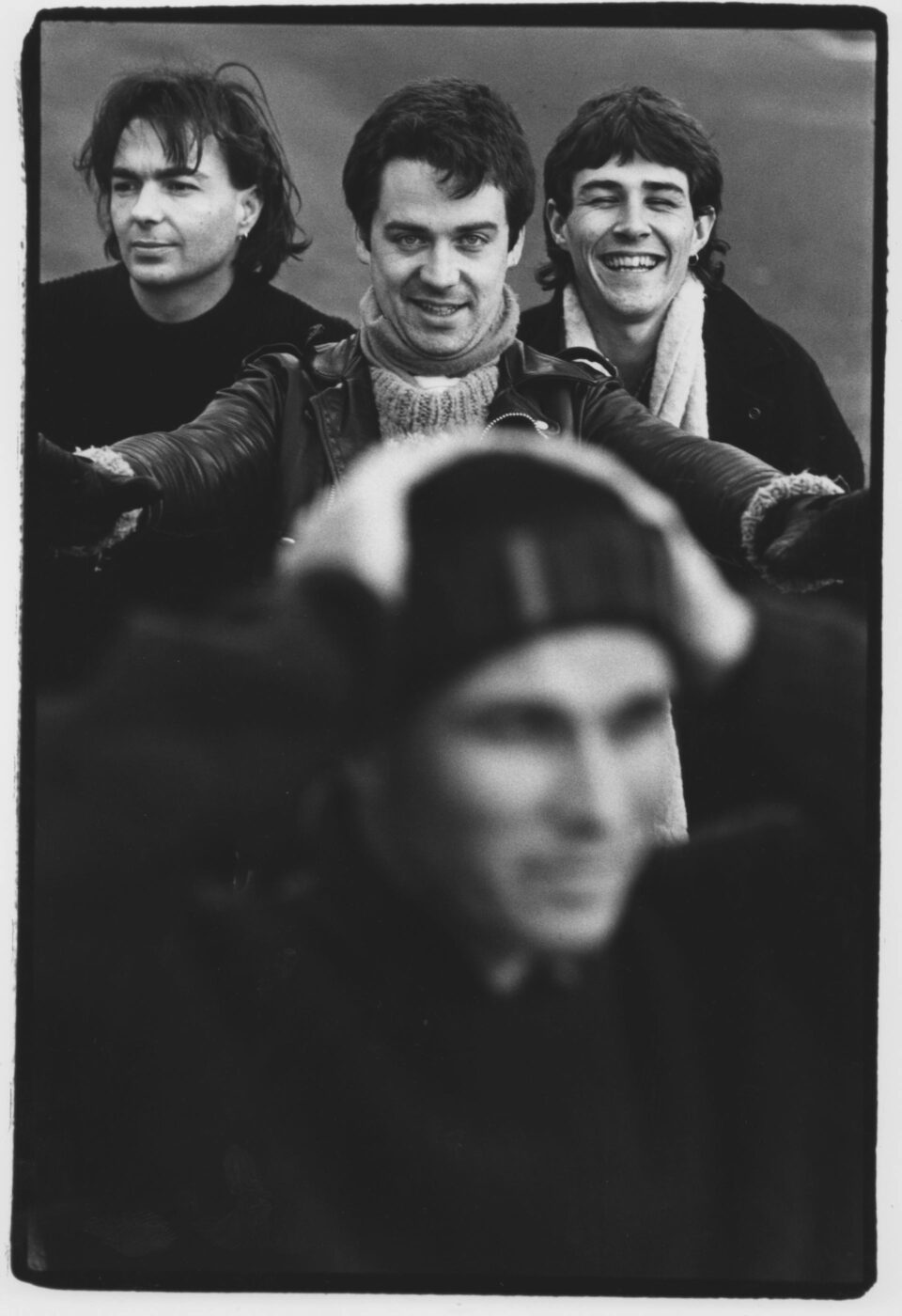

The Chills circa 1990

The band’s earliest chapter was defined by their robust, ringing, lo-fi pop records for the Flying Nun label, where thoughts of romance curdled like bad cream to their plush, increasingly harmony-filled recordings. With their melodic, cross-cutting guitars and occasional prog-rock twists, the rhapsodic Chills were worth the risk of fetishizing. An erratic genius such as Phillipps made infatuation easy and sing-song-y, and his death earlier this week—possibly from the effects of liver failure after an aged bout of hepatitis C and continued issues with liver disease—only makes the hearts of those who love and crave The Chills grow fonder. In the words of “Part Past Part Fiction” from 1990’s Submarine Bells: “I really didn’t choose to leave you / To tear myself away so long / To travel and unravel all the fabric we’d sewn / So now something’s wrong / And the world we used to know has gone.” If you wanted any bittersweet artist to continue along with his life’s mission and aesthetic, it was Martin Phillipps.

Going back to the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s, when most pop listeners were turning on to the new wavers and New Romantics, Phillipps had just bailed on the punk rock of his Dunedin, New Zealand–based band The Same in order to create the saltier, janglier contours of The Chills with his sister Rachel. If punk held any continued sway for Phillipps when it came to the bleak dreaminess of The Chills, it taught him how to best bear one’s teeth—grit, rather than a grin.

Though Big Star and the aforementioned Velvets played large parts in Phillipps’ musical influence, it was a steady diet of Byrds, Beach Boys, and Beatles records that not only inspired The Chills, but other bands lumped into the burgeoning “Dunedin sound,” such as The Bats, The Clean, The Verlaines, and Tall Dwarfs. Phillipps took the heartbroken, harmony-filled vocal richness and ringing, stinging melodies of his favorite bands, past and present, and rendered them without sentiment. In Phillipps’ hands, an “I love you” became an “I glove you,” and all of their cheery chiming chord changes were web-laced with black crepe and topped by gray-lined blue clouds.

Phillipps’ unique brand of musical non-sentimentality did yield the occasional indie-level smash for The Chills, such as the anthemic “Pink Frost,” “Doledrums,” “I Love My Leather Jacket,” and, no surprise, “Heavenly Pop Hit.” It also made him the only consistent Chill on their seven studio albums (including 1996’s Sunburnt, released under the name Martin Phillipps and the Chills), their lone live album (2013’s Somewhere Beautiful), and their lengthy list of EPs and singles.

Superchunk’s Mac McCaughan and Martin Phillpps / photo courtesy Mac McCaugha

One fellow artist and label owner who felt close to Phillipps from the start up to his passing is Mac McCaughan. Like Phillipps, a McCaughan-led band such as North Carolina’s Superchunk helped define a region and a mood (the billowy “Chapel Hill sound”), while his off-shoot ensemble Portastatic tested the limits of that cloudy aesthetic with something freer. Adding to the allure of starting such inspirational American bands is the fact that he and Superchunk bassist Laura Ballance co-founded the independent record label Merge Records to house all of their friends.

“Kaleidoscope World was maybe the first Flying Nun record I could find, in 1986, and that was an album that opened my eyes to a whole new world of New Zealand pop music.” —Mac McCaughan, Superchunk

As label owner, musician, zealous Chills fanatic, and acquaintance of the late Phillipps, McCaughan puts into perspective much of what many independent music minds are feeling at the moment. “Kaleidoscope World was maybe the first Flying Nun record I could find, in 1986, and that was an album that opened my eyes to a whole new world of New Zealand pop music,” he shares. “After that, we were on the lookout for any new Chills record. The first time I saw the Chills was 1987. We drove from North Carolina to New York City to see them play The Cat Club. This was with Caroline [Easther] on drums, so around Brave Words. They were amazing. I never saw a bad Chills show, even though the lineup was often different from the last time, and live they could be quite ferocious compared to the records. Martin was always kind when we met over the years; we recorded [a cover of] ‘Night of Chill Blue’ in 1993, and Martin was always the first to bring it up.

“The last time I saw the band was in 2022 in Durham,” McCaughan adds, “and they were, again, fantastic, and it seemed as if Martin was really on a roll with the last few records. It’s so sad to see him go.” FL

The Chills circa 1990