Given the fact that we’re several years into a moment in music and fashion that pulls directly from the late-’00s/early-’10s indie-pop scene, it’s only natural we’d slowly find our way back to where much of this movement began: the early-’00s dance-punk explosion. Recalling an era when groups like The Faint, The Rapture, and Foals began freaking out tweens eager to play the latest MVP Baseball iteration, Font arrived this year with a debut album of artful takes on the revival of post-punk revival. Strange Burden feels like the musical confluence of contemporary American noise rock a la Model/Actriz and rowdy British post-punk in the vein of Shame, albeit with a wholly unique intellectual agenda evident in the lyrics.

While some of their musical influences can be fairly easy to identify, the ideas that inform these songs can be a bit more opaque. Speaking with frontperson Thom Waddill and multi-instrumentalist Anthony Laurence, one can see why: Each of the five non-musical influences they cite feels deeply abstract, even when referring to an iconic American filmmaker or Photoshop feature largely associated with gimmickry or deceit rather than generative hallucination. It almost feels as if the new album’s title refers to the band’s self-imposed task of digesting these heady ideas and channeling them into something more concerned with merely getting the body moving. As Waddill puts it, they subscribe to “the idea that art isn’t meant to convey the complexity of living, but rather to recover its simplicity.”

With Strange Burden out now via Acrophase Records, check out their five non-musical influences below. You can order the record here, and if you’re in Austin you can catch their release show this Friday at Parish.

Stanley Kubrick

Thom: The Shining was the first Kubrick I saw. I’ve always been pretty squeamish when it comes to horror, but in college I remember having an awful and very sad nightmare and waking up with the urge to finally watch The Shining. Over the years my impression of Kubrick as an artist filled out as I watched the rest of his films, which together form a collage-like whole. I’ve found a fabricator’s allegiance to craft and form balanced by an artist’s willingness to push the work into the intensity of the unknown. Because of that, he threads an important needle for me. He never repeated himself. The identity of his art was clarified by these experimental jumps from genre to genre, yet through that he was always able to avoid pastiche and parody. He just sort of did everything, and did so.

Photoshop’s AI Generative Fill Function

Anthony: This function is intended to add/remove subjects from photos—prompts like “remove people” or “add waves.” However, using more ambiguous prompts like “movement,” “discover,” “jest,” etc. on a subject can yield some super uncanny results. The generated images often have a micro familiarity and macro indecipherability. Sometimes vice versa. The result is usually stupid, but occasionally super interesting. Logically, I understand the results as an instant pattern-based decision, but it’s fun to imagine it as a flicker of artificial creativity. There’s also something about a hyperreal technology confidently creating something indiscernible. We recognize the high-fidelity textures and shapes and glints of light, but our categorization of the whole struggles and ends at a simple cataloging of parts. This friction is sometimes spooky and inspiring. In practice, an AI model confidently producing an incorrect result is called a hallucination.

Superstition

Thom: The superstitious mindset is essentially, I think, one of perpetual interpretation. To the superstitious, the world is a mass of signals. Superstition is the aestheticization of chance. This is an inspiring idea to me, and feels consonant with the creative mindset. I think an artist is constantly “reading” the world. It’s delusional and deeply human. I think of all the activity it inspires: baseball players in unwashed jockstraps on a winning streak, goat’s blood on the doorframe to stave off the angel of death, wearing my good shirt to the first day of fourth grade in hopes I’d be in the same homeroom as my crush, drachma on the eyes of the dead.

One summer when I was a kid I played Moses for a children’s Vacation Bible School play that staged his receiving the Ten Commandments. I happened to be thinking about that a lot when we were writing “The Golden Calf.” The ritual violence, complexity, and superstition-related massacre of Exodus 32 after Moses descends from Mount Sinai seem in hindsight like a funny tableau for children to stage. But all of the foundations of superstition are there in children: all of the rage, fear, and awe, from which proceed the desire for the nonhuman world to be a thing with which you can communicate. I know that I was—and continue to be—a superstitious child in a gray fright wig.

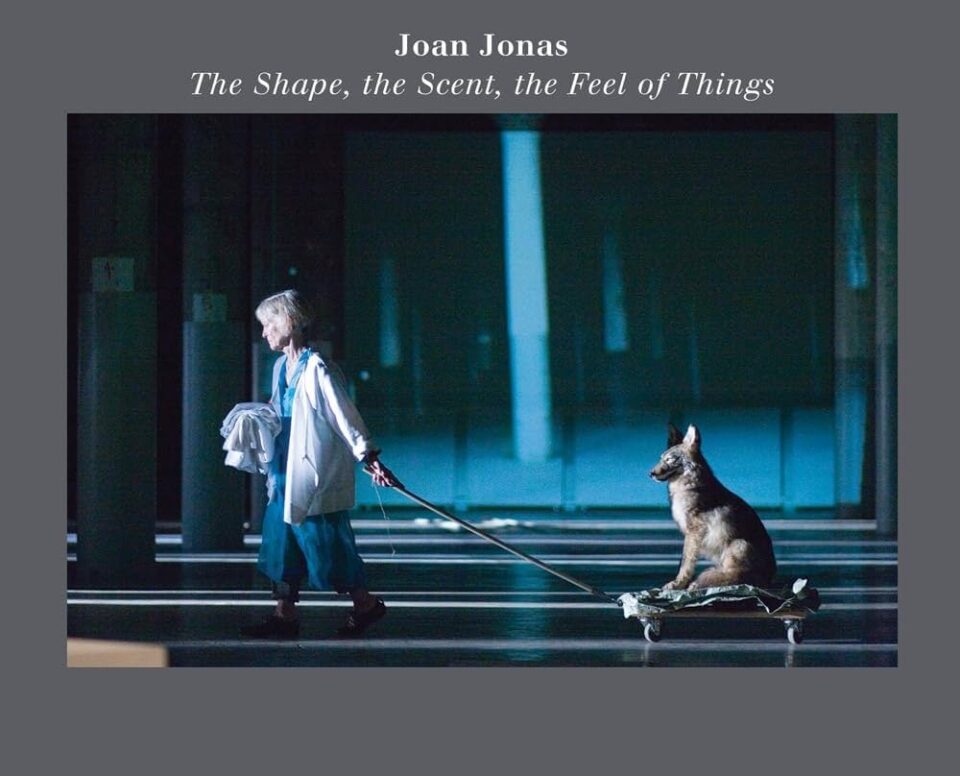

Joan Jonas: The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things

Anthony: At a gallery in Chelsea, I picked up a catalog documenting this performance by Joan Jonas. I liked the cover of the book and was previously unfamiliar with her work. To be honest, I found the performance difficult to follow as it read on the page, but I was instantly taken by pictures of the performance. Industrial spaces where scenes of minimal, essential mise en scène were backed by large video installations of natural imagery. Shortly after getting this book, we began discussing the “Natalie’s Song” lyric video. We wanted to mess around with superimposing images and projections in a large physical space. A big part of the idea—and, more importantly, how we communicated it—came from referencing Jonas’ work.

Deborah Hay

Thom: Deborah Hay is a postmodern dance legend who’s been in Austin for a number of decades now. I was exposed to her in the beginning of 2023 when I went to a couple performances hosted at UT; she did a solo performance called my choreographed body… revisited, and then a troupe did a piece that she choreographed called Horse, the solos which was scored by Graham Reynolds. Her solo performance was musicless; the large concert hall was completely silent except for the irregular shuffling of her feet and her spontaneous vocalizations. Her movements seemed to pull from a great range of registers of human gesture.

Not only did I not really know who she was before that, but I also had never really had an experience with dance that moved me. Her solo, within a couple minutes, seemed to reveal the entire medium to me. I understood then that it has something to do, essentially, with liberation. Her movement was called “dance” because it was free. Later I’d read My Body, the Buddhist (which I’d recommend to anybody interested in what it means to be creative) and participate in a couple workshops with her, which were a big inspiration for the “Hey Kekulé” video. In those sessions, participants—aged 14 to 72—just moved for an hour in a quiet studio (crawling, posing, interacting, bouncing, balancing, etc.), during which Hay would intermittently repeat these koan-like phrases. Taking part in that was one of the more profound experiences of my life. Her solo and those workshops left me with the idea that art isn’t meant to convey the complexity of living, but rather to recover its simplicity.