Dorothy Carter

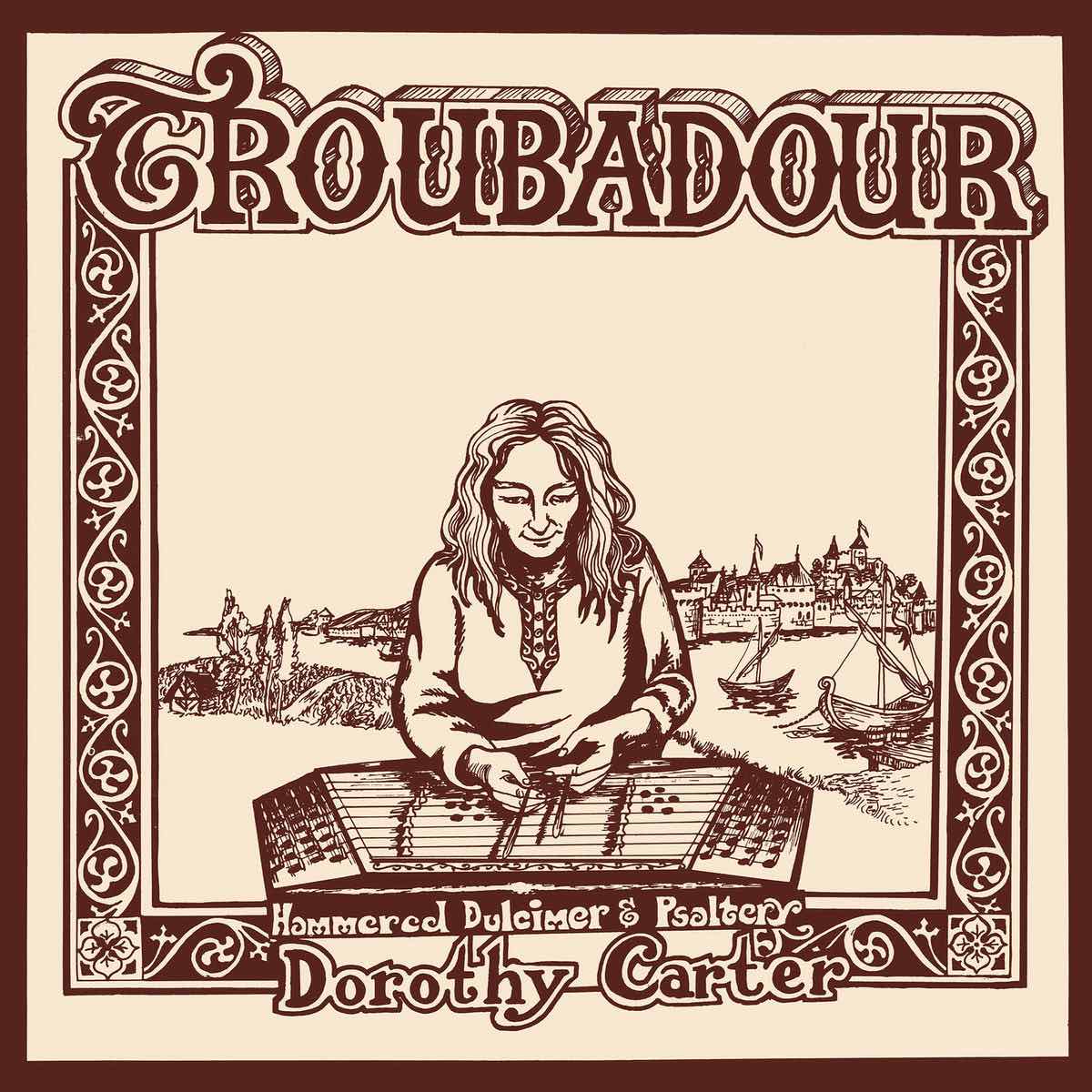

Troubadour

DRAG CITY

By the time Dorothy Carter passed away in 2003, she’d become an icon of hammer-chord-stringed instrumentation and contemporary Celtic-folk vocals with the ensemble she co-founded in the 1990s, Mediæval Bæbes, and the improvisational space sounds of the Central Maine Power Music Company in the early 1970s. Yet on her own, with two solo albums to her name, Carter became beloved for her brand of experimental psychedelic folk that had little connection to any tradition, save for paving the way for the 2000s-era dedication to all things “freak folk.”

While 1978’s Waillee, Waillee was the better known of Carter’s two solo albums, with its creepingly crepuscular and outré cosmic takes on French Appalachian and Celtic folk, it’s the ancient-to-modern Troubadour from 1976 where she truly flies her freak flag. Like a Sun Ra of the folk scene, Carter took no prisoners with her wild-eyed vision of what internationalist traditional music could be when unconsciously unbound to convention. A traveler in the literal and figurative sense, and a dedicated collective member, Carter brought her far-and-wide distance and communion to this self-released debut solo album (now re-discovered and re-released by Drag City).

While songs such as “Binnorie” and the “Troubadour Songs on the Psaltery” medley (a “psaltery” being a dulcimer played by plucking its strings) are steeped in aged, varied, and vague feels for foreign intrigue, Carter originals such as “Make a Joyful Sound” do just that with their high, delicate vocal call to God and the singing of His praises. The droning heard on that track is dreamy hammered dulcimer struck in a way to make a percussive, hypnotic tone with shaman-like singing to welcome (or scare off) the holiest of spirits. The same can be said—only more so—of “The King of Glory” and its extended mesmeric mix.

From there, the rest of Troubadour revels in ripe, rare, spaced-out mysticism on the psilocin-like “Tree of Life” and the ethereal prayer that is “Shirt of Lace” and a cultured-pearl classicism that warms the elegant likes of “The Morning Star” and “Balinderry”—or, on original compositions such as “Masquerade,” it drifts along epically with gleeful melody and bone-crunching percussion as its guide.