Brooklyn-based illustrator and graphic novelist Brian Blomerth never tires of tripping. Whether it’s the long story of Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann and his discovery of LSD (Bicycle Day) or the fancifully winding tale of scientist couple R. Gordon and Valentina Wasson’s research into magic mushrooms (Mycelium Wassonii), Blomerth creates lush, textural art volumes worthy of the deepest plunge into the psychedelic mind-body state. Intergalactically spacey, yet oddly earthen with a real feel for flesh and fur and the rhythm of comic-book pattern and flow, the artist’s steady focus on the purpose of history is his melodic base, with the energy of improvisation steering his hand. If you could compress the lysergic tour of Ken Russell’s phantasmagorical Altered States with its mystical primitivism onto the page, with a dash of R. Crumb’s free-comic line and a taste of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Brian Blomerth would be your spirit guide.

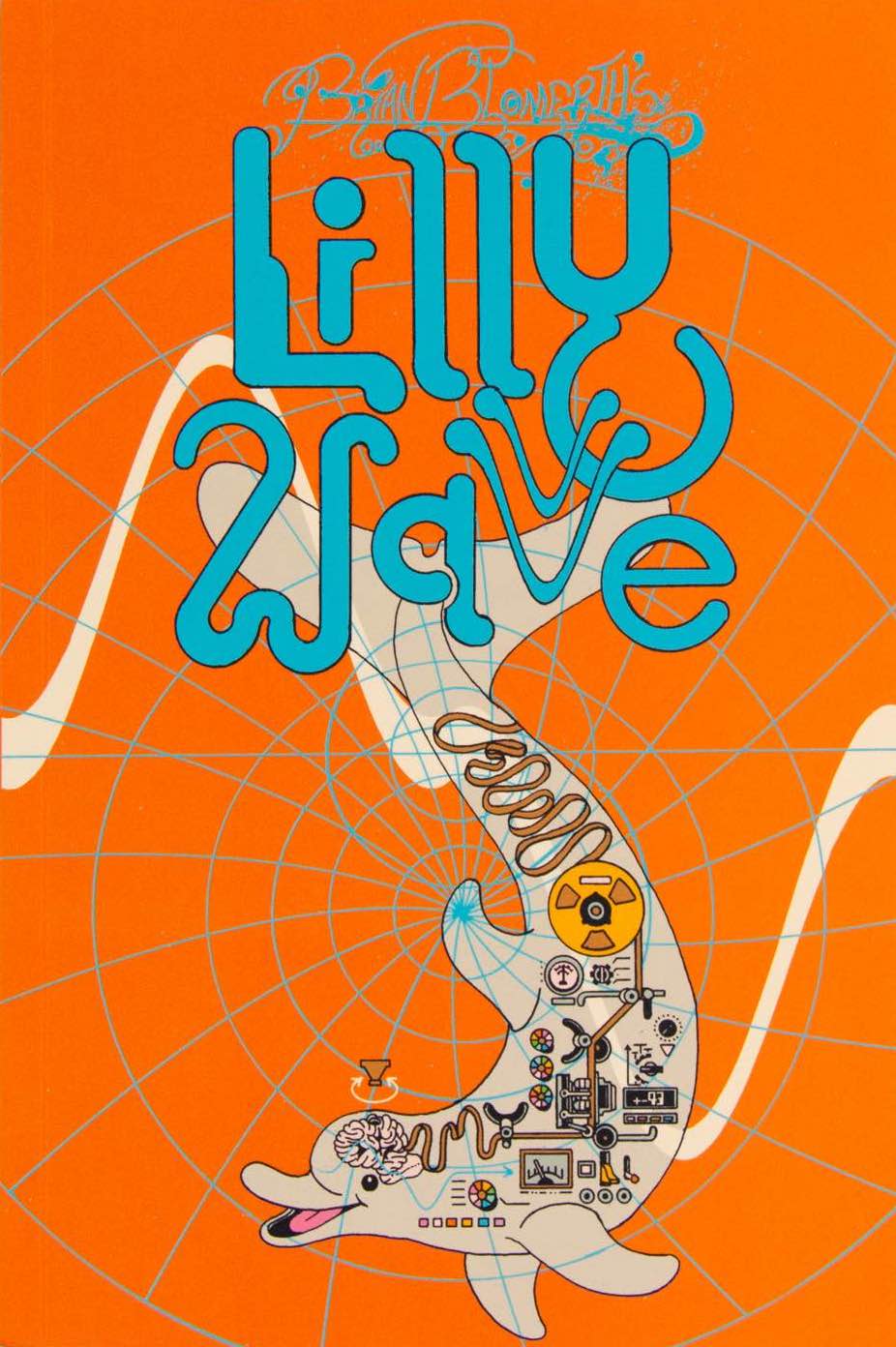

Russell’s gently smiling dolphins, exploding cosmos, and depictions of isolation tanks, too, figure heavily into Lilly Wave, Blomerth’s wild new world vision for a volume on the legendary ketamine researcher John C. Lilly. Dangerous in the wake of headlines about Matthew Perry’s death (and rightly so, if addicted) ketamine is a radically different trip than cold liquid mescaline or gummy psilocybin mushrooms. There’s often a dreamy numbness to ketamine that throbs throughout the trip, a nose-tip-to-toes sizzle that aids in taking its user out of the picture. Altered States was inspired by the work of physician, neuroscientist, and “psychonaut” Lilly, as was the film The Day of the Dolphin, and—in a far more innocent way—TV’s Flipper.

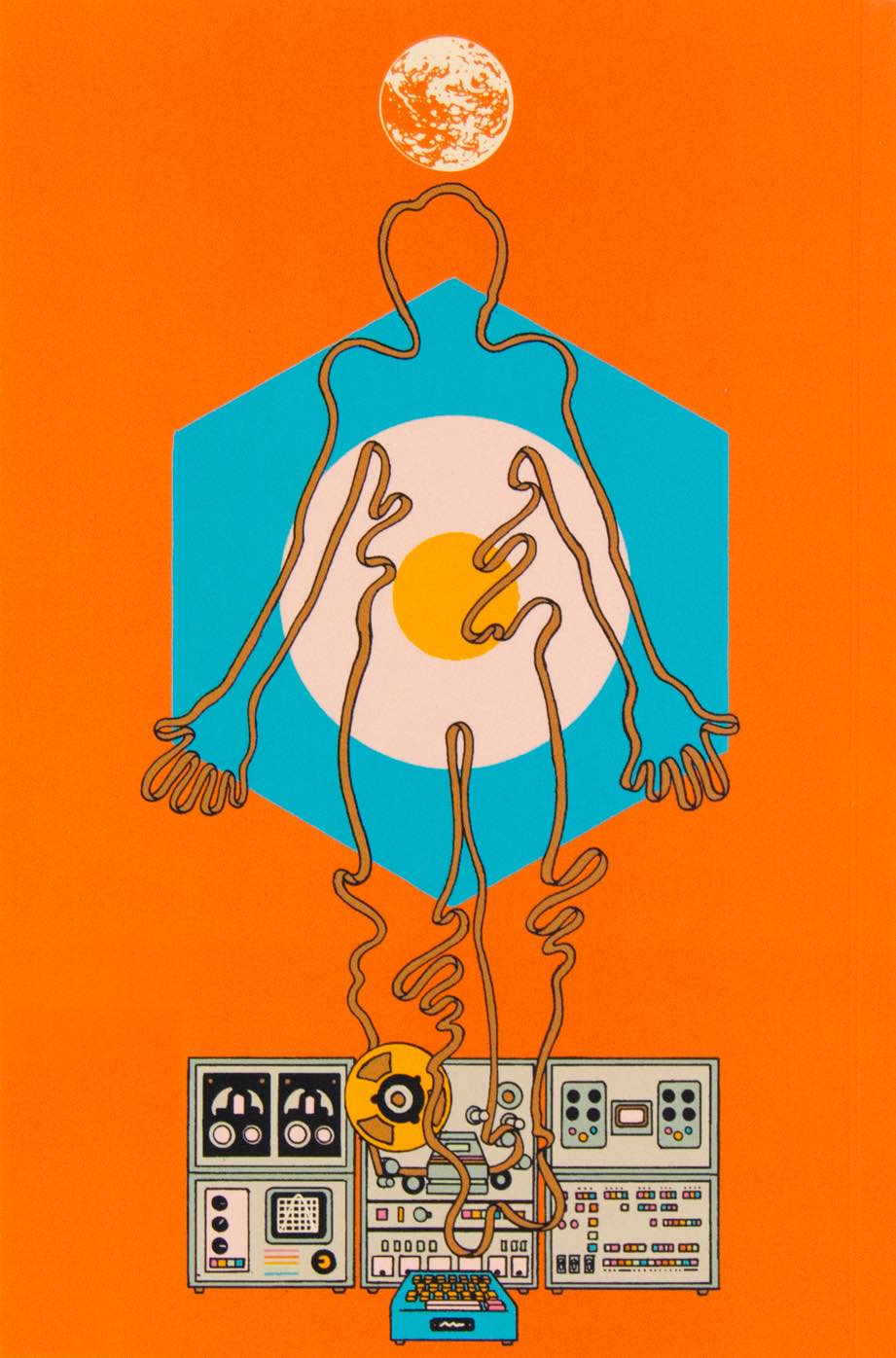

Lilly ran with a fast (or slow, depending on the drug) counterculture crowd that included Werner Erhard and Timothy Leary, inspired the likes of Carl Sagan, and tested the limits of the human mind and the whiles of psychic locution with his in-flight war research on high-altitude limitations and underwater testing via his development of the isolation tank. Depriving the mind of all external stimuli, Lilly believed that he could deeply mine the human consciousness for all of its gold, and make a new future communication form that could speak through the cosmos (Lilly was also fascinated by the reality of alien life, even forming his own Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) project at the top of the 1960s). And what better way to alchemize the mind’s expanse than to liberally sprinkle in psychedelics while floating endlessly in isolation?

Ketamine, however, was a different animal. Though the drug can be valuable to arresting depression and migraine headaches, Lilly fell both literally and figuratively into the K-hole, a tingling numbness that becomes a vacuum where time, tide, space, and one’s own soul become interchangeable, endless, and eventually, blank. Ketamine is the great eraser, and a mind explorer like Lilly surely felt immune to the dangers of continued usage.

Blomerth portrays those risky highs with skies and seas filled with smiling dolphins, visually arresting animal prints, cheerful atomic symbols, vibrant radio waves, and spirographic dives into slithering consciousness. Fleshy brain stems, shadow stars, specter hands, alarming clocks, towering Tables of Elements, silly seahorses—they all spin endlessly, guided by Blomerth’s mix of thin squiggles and bulbous blob work and the figure of Lilly as a floppy-eared dog having a great time while testing his limits. An early example of one of Dog-Lilly’s thought bubbles moves from joyous discovery to dismal rant in mere seconds. “Hallucinations/waking dreams: starmaker. Birth + memories of childhood. Visual static became galaxy-like. Brother thrown from horse. Pilot whale from Cape Cod alive and smiling at me. Saw myself hammering 1/8 electrode lead into my own brain—a peculiar and distressing repeat fantasy of my mind.”

Though Blomerth’s illustrated trip is filled with rounded R. Crumb characters shouting out “Howdy” (a nod to Creem magazine?), masturbated dolphins, and a wealth of discoveries outnumbered by their tragedies, the journey really sours when Dog-Lilly pushes his dolphins (and those at work and in love with him) to unthinkable heights and depths until—“seduced by ketamine”—the good dog doctor has nothing left but his belief in “duty” to “mapping and exploring” whatever new reality he believes he’s found in an endless void of dully twinkling stars, squeaky balloon animals, and blank, tongue-wagging ghost imagery.

By the time Blomerth ends Lilly Wave’s story with a loop-de-loop hand-drawn font epilogue, its squiggly descent signals its subject’s time (in this stratosphere, at least) and energy waves having run into the eternal K-hole as the credits roll on, like a film’s last reel lapping and flapping into infinity. The history, mystery, and power of psychedelic drugs is Blomerth’s game, and he never loses. Though I’m curious to see where the artist can go next, Lilly Wave is a great high to rest upon.