Audiences are changing; Charles Thompson isn’t. The 59-year-old Pixies frontman (also known, in various incarnations, as Black Francis or Frank Black) has always been averse to unnecessary theatrics. “We play our music,” he tells me. “There may be a little presumption among some audiences nowadays that people need to ‘perform,’ also. It’s enough of a challenge to get us to not only play, but to play it on a stage, in front of people. We’re already grappling with enough there!”

Thompson and co. have applied this “less is more” philosophy to Pixies shows for decades. The band doesn’t adhere to a predetermined setlist, and avoids speaking between songs at their shows. Today, it could register as an implicit repudiation of audiences who are inclined to avoid art that makes them uncomfortable. “They don’t want to be confronted with a lot of antagonistic energy,” Thompson says. “I can understand that. I’m not as afraid of an antagonistic energy—or at least an energy that’s not so hand-holding of the audience.”

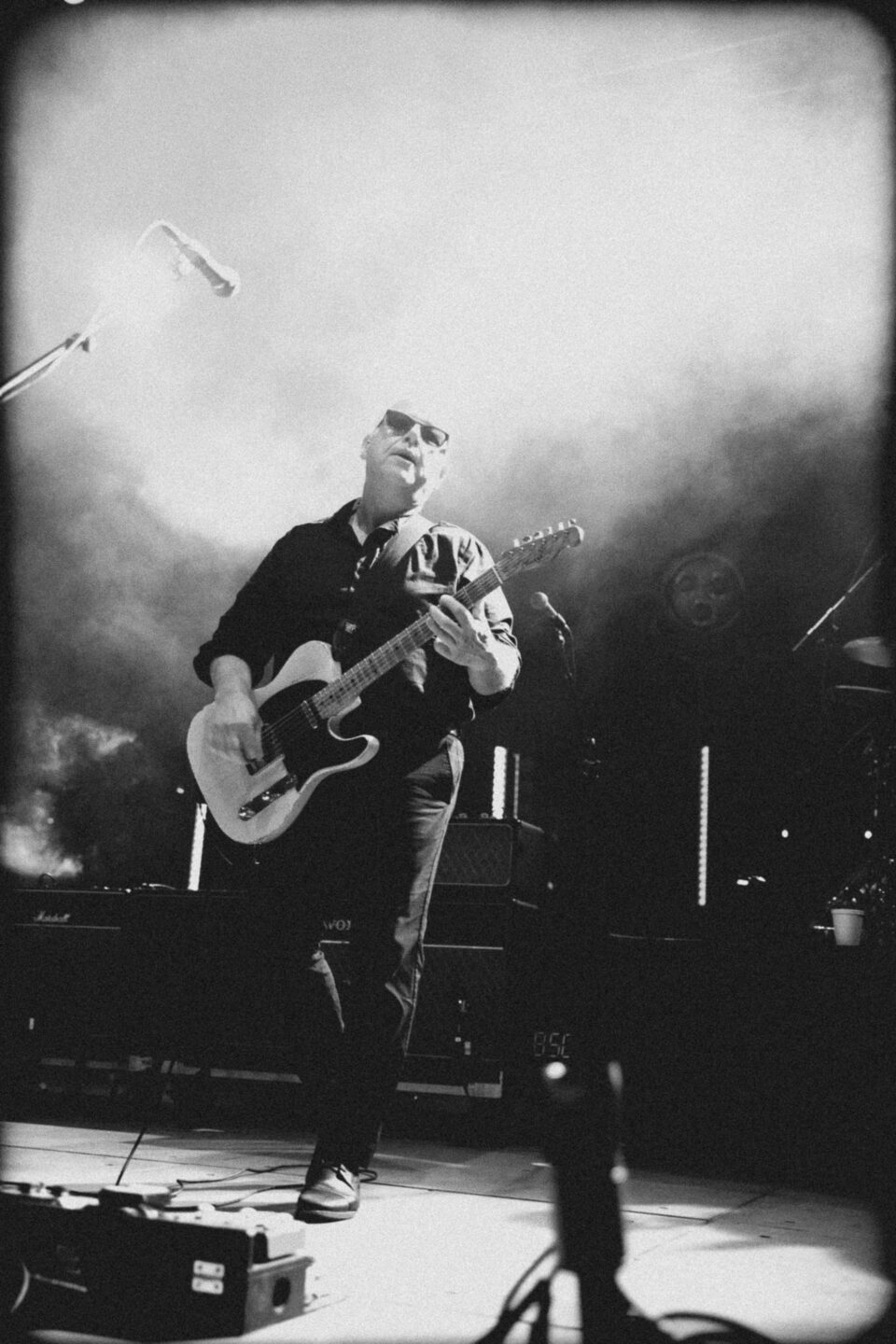

photo by Liam Maxwell

This won’t surprise longtime followers of the Pixies, a wildly influential band who have charted their own path since their rise to prominence in the late 1980s with culture-shifting records like Surfer Rosa and Doolittle. But for all of the band’s surface prickliness, the most recent Pixies records hum with a warm familiarity. The Night the Zombies Came, the tenth Pixies album, deploys all of their sonic hallmarks but continues to explore them from fresh angles. Unnerving and funny, “Chicken” is likely the year’s most effective song about bird decapitation. The eerie “Jane (The Night the Zombies Came)” is thick with B-movie imagery and a rich gothic atmosphere. Its selection as the title track, though, shouldn’t be overread: “I don’t want to elevate the song to too high of a status, because that would be misleading,” Thompson says. “It just has to sound cool as a title.”

Zombies is the fourth consecutive Pixies album produced by Tom Dalgety, who the band views as an essential partner. “He knows all of our personalities,” says Joey Santiago, the band’s lead guitarist and co-founder. “We have the same language.” Bassist Emma Richardson of Band of Skulls recently joined the Pixies, and she credits Dalgety with ensuring the sessions were both productive and fun: “He’s led by intuition and instinct. He’s got a good knowledge of what the band wants.” Thompson credits him for keeping the band focused: “He seems to be a very good manager of time. His planning is, generally speaking, a thing that’s helpful, as opposed to something that’s cramping my style.”

photo by David Iskra

“I’m not as afraid of an antagonistic energy—or at least an energy that’s not so hand-holding of the audience.” — Charles Thompson

Though new to the band, Richardson emerges as an essential ingredient of The Night the Zombies Came. She describes her experience recording with the band as a dream come true as a fan, and deeply engaging on a creative level. Her vocals, which figure prominently throughout the album, lend the songs a unique texture, and she found that she was granted a creative freedom that frequently nudged her outside of her comfort zone. “It was great figuring out what the song needed,” she says. “I didn’t want to do too much, but the door was open for me to try some stuff, which was incredible.”

Santiago takes an expanded role on Zombies, having written the music for “I Hear You Mary” and the lyrics for “Hypnotised.” “Charles is one of the best lyricists around,” Santiago says. “And when he asks me again to [write], I say, ‘Are you high?’” But Santiago found the assignment simultaneously daunting and invigorating—even when he was ultimately tasked with finishing it on unexpectedly short notice. “Tom called me and [said], ‘Charles wants to sing the song in an hour.’ But it’s a fun process, I have a blast with it.”

Notably, The Night the Zombies Came sounds at ease, the work of a band with plenty left to say (indeed, both Thompson and Santiago confirm that they’ve already started work on a follow-up). The stylistic shifts throughout Zombies highlight the band’s long-established versatility, but it never feels showy or overly calculated. “It’s just in our DNA,” says Santiago. “Expect a Pixies record; it’s all over the place. There’s punk, there’s hard rock, ballads…weird songs, and just straight-ahead nice pop stuff. We’ve got a version of ‘Here Comes Your Man’; we’ve got a version of ‘Tame.’” That’s part of the appeal of Zombies: its willingness to dialogue with the band’s past, a specter that will inevitably loom large whether they directly engage with it or not.

Thompson is revisiting his solo work as well, planning a tour in celebration of his beloved 1994 album Teenager of the Year (released under the Frank Black moniker). Teenager, recorded shortly after the Pixies’ initial break-up a year earlier, is now being remastered and reissued for its 30th anniversary. Thompson is planning a series of shows in the US in January where he plans to play the album in full. He remembers the recording of Teenager as a period of intense creative focus. “I suppose it would’ve been a little bit of the spirit of indulgence,” he says, “not so much in how much money we were spending on the record, but more in the amount of work that we were doing. There was no spare time.” Even more importantly, he found himself unshackled from the interpersonal turmoil that had consumed the Pixies just before their breakup, as well as the growing weight of expectations associated with that name. With Teenager, Thompson says, “there wasn’t any notion of, ‘Well, what is this going to sound like if and when we go on tour with it?’ or, ‘What will be the single?’ or, ‘What will the Pixies fans think of it?’ It was all done perfectly in a vacuum.”

“Expect a Pixies record; it’s all over the place. There’s punk, there’s hard rock, ballads…weird songs, and just straight-ahead nice pop stuff.” — Joey Santiago

Thompson is no stranger to critical reappraisal. Rarely has that shift been more pronounced than with Teenager of the Year, which was greeted with a curiously icy reception upon release. Critics initially seemed eager to repudiate Thompson’s break from the Pixies; decades later, it’s rightfully recognized as one of the great rock albums of the 1990s. “I don’t think that in general, I make records that are immediately likable,” Thompson says. “I think it just takes time for people to come around to maybe have a better understanding of it. You just need to listen to it a few times before you can feel the wavelength of it.”

It’s interesting to see Thompson revisit the past given how unsentimental he is about his catalog. He’s quick to note that he isn’t doing it as a means of self-mythologizing. “I certainly think fondly about the repertoire. Otherwise, I don’t think I’d be doing it. But I’m not so estranged from my own music that I necessarily perceive it in a very different way years later.” Instead, he says, he’s animated solely by the music, which continues to resonate with fans. “There’s plenty of sentiment being expressed in the music itself. So if it’s sentiment you’re looking for, that’s where it is. It’s not going to be in celebration of me. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not humility. I just have other shit to do.” FL