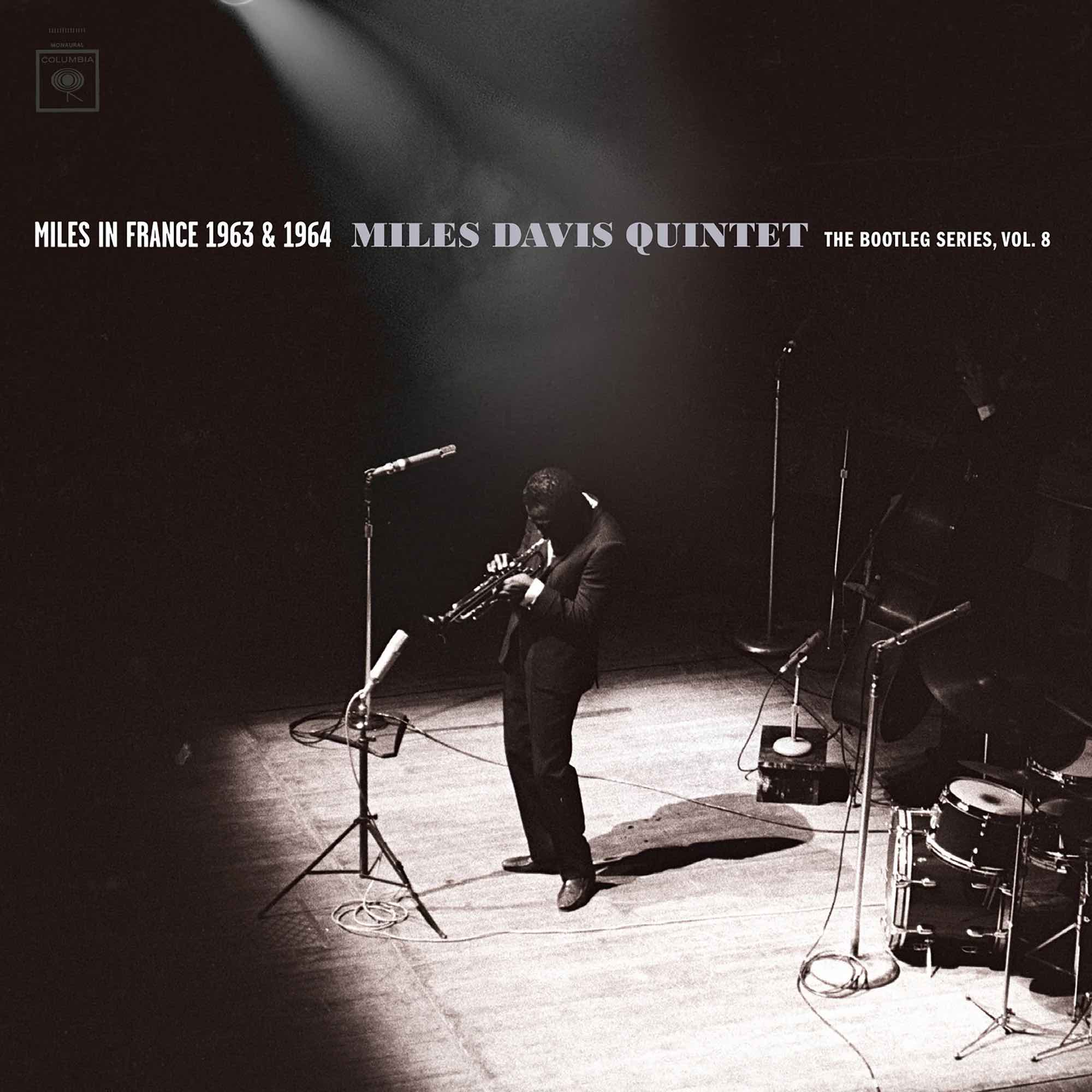

Miles Davis Quintet

Miles in France 1963 & 1964: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8

LEGACY

Like Jerry Lewis and Mickey Rourke, trumpeter-composer Miles Davis has long been a hero in France—that is, without the former’s laugh track and the latter’s poseur machismo. That’s not to say that Miles’ brand of incendiary jazz circa 1963 wasn’t deeply masculine or without humor. If nothing else, his epic, beloved Second Great Quintet (pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams with saxophonists George Coleman and Wayne Shorter) was always embraced by Parisian audiences, representing that era’s most muscular yet gently nuanced music while rippling with Davis’ fiery sense of innovation and freedom (not to be confused with “free jazz,” however).

Re-released now with over four hours of previously unheard music, these legendary concert recordings are historic beyond their moment as they famously portray the sound of one Davis era’s end and another’s beginning coming through, all at the same time. Everything within Miles in France is intense, a bespoke suit-and-sweat-drenching thrill ride from the algebraic, elongated “So What” and evenly coursing “All Blues” into the soulful balladry of “Stella by Starlight” and “My Funny Valentine,” the frenetically paced “Walkin’” into the Impressionist’s delight of “Seven Steps to Heaven.”

Though it’s often been said that sax man Coleman was but a prelude for Shorter on the 1963 portions of Miles in France (the trumpeter wanted an elusive Wayne for some time at that point), make no mistake: Coleman’s ax is lyrical and bright, and need not exist in the shadow of Shorter’s spirited, soul-stirring invention. Besides, it’s nearly impossible to listen past wild Williams’ out-of-bounds drumming. Mad paradiddles, frantic near-polyrhythms, pulsating bumps, and free grooving rhythms: it is, at times, maddening. Then again, you listen to “Autumn Leaves” and Williams’ more subtle brush work and cymbal shadings are masterfully somber and light as they bleed into Carter’s sweet and salty bass lines.

And Miles? He’s bending space and time on 1963 moments such as “Stella by Starlight,” leaning into his blue notes coolly without ever letting his French audiences forget the intensity he’s kept in his back pocket with a sensual bleat here and a lengthy roar there. When Shorter’s employment starts, it’s as if there’s a whole new band at work with another purpose: to find each other’s centers and make an intellectual, theoretical mess without ever missing the head. Miles’ uplifting, mesmerizing solo on “Walkin’” in Paris, for example, is a metaphysical gamechanger as it allows the new saxophonist to compose something complex on the spot, something tone-crunching and tense, yet luminously melodic.

Staying in Paris, Williams and Davis punch the fuck out of each other during “Joshua,” with Hancock as the recording’s loud, hypnotic referee. Hour after hour throughout Miles in France is just this: the magically abstract sound of five men during just one of their peaks, outdoing the other while working as a whole, all in the name of their fearless leader.