It’s official: This has been the Year of Redd Kross—a celebration that’s been long-overdue. Nearly half a century after forming one of the most important bands to ever hail from Los Angeles (and “the most underrated band of their generation,” according to Variety), in 2024 the power-pop/bubbleglam/hardcore band released their most ambitious album yet, the 18-song, two-disc Redd Kross, plus a delightful memoir, Now You’re One of Us. And now the year wraps with the release of their documentary Born Innocent: The Redd Kross Story, directed by former Friends writer/showrunner/executive producer Andrew Reich. The movie opens at the TCL Chinese Theatres in Hollywood this Thursday, with additional screenings around the country scheduled through next year.

FLOOD asked rock’s coolest brothers—Hawthorne-born, Hollywood-raised Jeff and Steven McDonald, who started the band when they were, respectively, ages 15 and 11—to bring us deeper into their world. Here, the McDonalds take us on a magical, mystical, mythical tour of Redd Kross’s Los Angeles.

CATHAY DE GRANDE, 1600 Argyle Ave., Hollywood

JEFF McDONALD: It was a very grubby Hollywood scene back then, where there'd be Paisley Underground power-pop bands playing with death-rock and junkie-rock groups. Everyone played their most insane, sloppy, drunken, crazy show there. We would go on at 1:30 in the morning and there were always disasters. We did a show with Black Flag and the Bangs—later the Bangles—but the shows I remember the most were the Mentors, with El Duce making fake skidmarks on his longjohns with A1 sauce before he walked onstage. It was just the dregs of Hollywood and a kind of druggy, dark, weird period; the bands were all on pills and the cops were always around and everything was a nightmare. But it was fun, looking back, having survived it.

STEVEN McDONALD: Jennifer Finch of L7 was, like, a teen photographer then, and she documented those couple years really quite brutally and beautifully. Those photos really take you back to that moment.

JEFF: Then it became the China Club, like this bottle-service-style nightclub, in the late ‘80s/early ‘90s. One night, Paul and Linda McCartney did one show at The Forum and there was a rumor that they were going to perform at the China Club afterward, so that was the only time I ever went. It was strange hanging out behind this red velvet rope and seeing people like Sly Stallone; we had no idea how that whole scene worked. But for some weird reason, they let us in. And there was no Paul McCartney, but a very skittish Elton John did do a brief set.

IHOP, 7006 Sunset Blvd., Hollywood

STEVEN: In 1979, when I was 12, [Black Flag frontman] Keith Morris once picked us up on his way to Hollywood in his gigantic beater car. We had a hellride of a night with Keith as…I dunno, the responsible adult in charge, I suppose? We were all going to the Hong Kong Café downtown, and afterward, there was this whole series of Keith hopping from party to party. We were at Keith's mercy. He probably decided he wanted to sober up before driving us back to the South Bay—that's my adult interpretation now—so, we went to the IHOP and we stayed there until the sun came up. I remember the sinking feeling in my stomach as it went from being late, to really late, to, “I don't even know if we can go home now, it's so late!” And I was 12! I needed to get home! If it was a weekend, I would've had my newspaper route, and if it was a weekday, then I was going to be late for school. And none of it was OK.

JEFF: I think we talked our parents into going out on a school night, which was a big deal. But because Keith appeared to be responsible and we were going to be with an “adult,” they let us go. It really was gnarly to have to come home at dawn after pushing that narrative.

Titles on the marquee for “A Shot Of Whisky,” a documentary on the Whisky a Go-Go, West Hollywood, California. 25 October 2008.

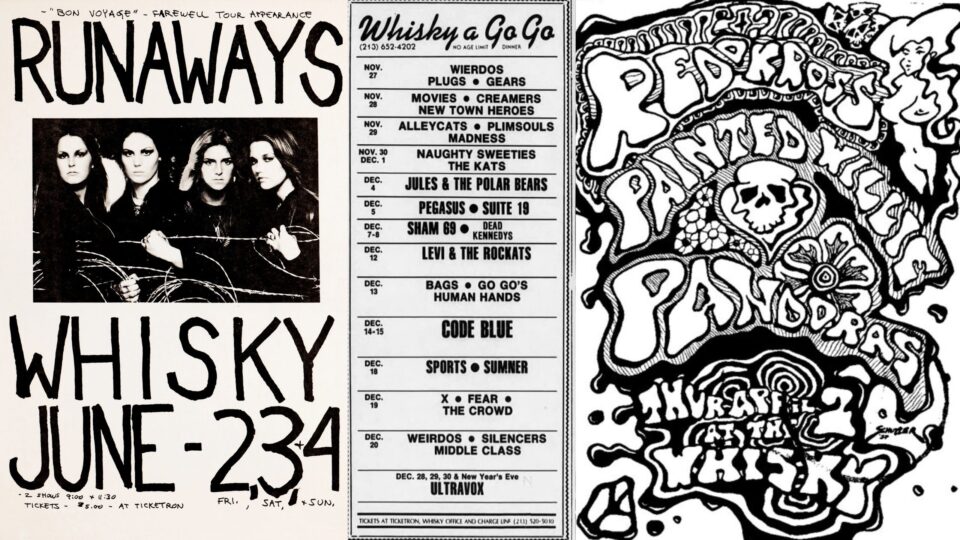

WHISKY A GO GO, 8901 Sunset Blvd., West Hollywood

STEVEN: We didn’t have necessarily progressive parents, but we just were so persistent, and our parents at least had the good sense to know if their kids were into something, they should be supportive. We would beg them to take us to the Whisky. They didn't know what these places were, but they would drive us there and then park and sit and wait, in a ‘69 Toyota Corona, at the Arco station across the street. We'd have to have a real good pitch, like, “Oh, mom, dad, it's The Runaways! We have to see The Runaways!” They understood, because we were playing the first Runaways record all the time.

JEFF: The Whisky was our very first time ever seeing a band in a nightclub. We’d been to big concerts, but not up-close and personal with these new bands that we had discovered through listening to Rodney Bingenheimer's show. We saw X and the Avengers; it took a month to talk to our parents into driving us, and it was probably for my birthday or some weird thing. I also remember seeing Joan Jett and the Blackhearts there, so it was our first time we ever saw rock ‘n’ roll celebrities. To see Joan Jett in person, just hanging out, was mind-blowing to us.

STEVEN: In the younger Redd Kross days, I think people would often come to our shows just to see if we were going to brawl onstage. We would never let our parents come see us play—we were just too embarrassed to be playing some really shitty punk club—and even when we were playing the Whisky, we still wouldn't let them come. But they came without our knowledge, and it just so happened to be one of those nights when Jeff stopped singing, so I started singing, and it was all lyrics about what a fucking asshole my brother is, probably. Eventually some guitars flew off and there was fisticuffs live onstage at the Whisky a Go Go. Afterward I was like, “Oh, I wouldn't have punched you if I'd known Mom and Dad were here!”

JEFF: We once played the Whisky opening for Killing Joke during our Born Innocent period, and they were really rude to us. They wouldn't let us in the backstage area, when they were putting on their combat camo makeup.

STEVEN: That was the first time I'd ever dealt with another band's outrageous demands, and one of their demands was that none of the support groups could come into the backstage.

JEFF: Whoever booked these little innocent teens playing with this British industrial kind of scary band, I don't know. They were on a star trip. But it was a thrill to be on that stage. However, that stage sounds awful. Out of all of the clubs I've ever played in Los Angeles, the Whisky has the most unforgiving sound onstage. It sounds fine in the audience, but when you play, all you hear is your guitar blasting in your head, and it's just like, “Ugh.” Anytime you see footage of the Whisky, know that the band is suffering, because it's brutal up there.

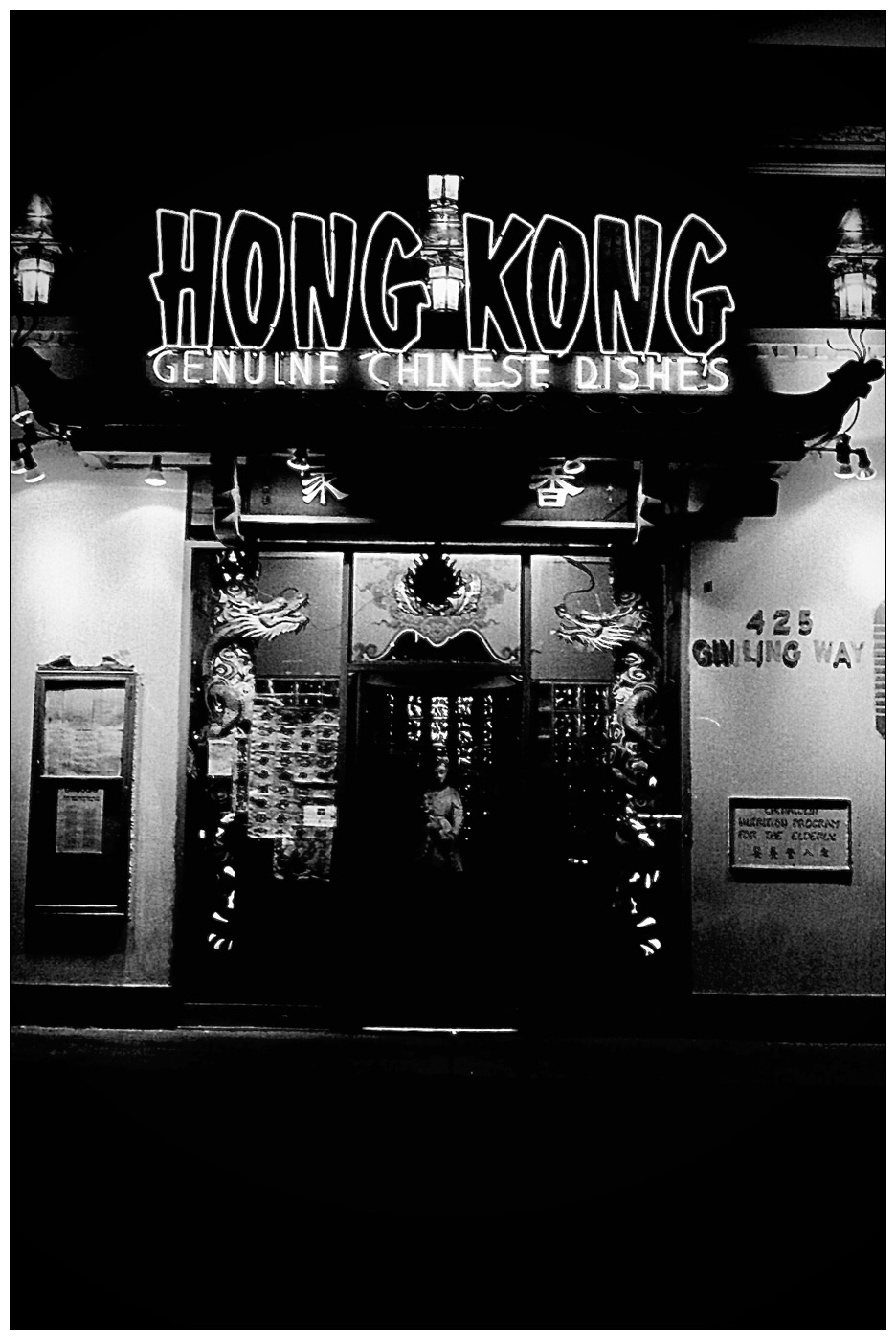

Hong Kong Cafe / photo by Edward Colver

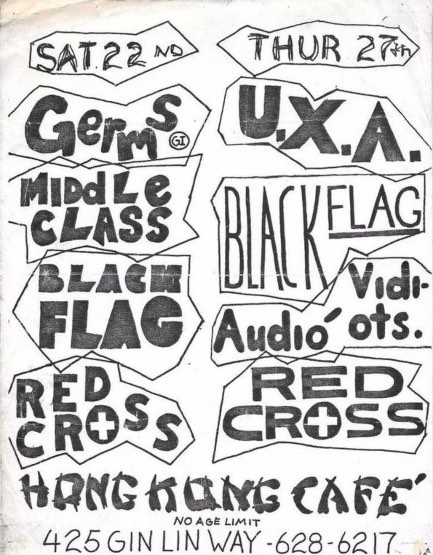

HONG KONG CAFÉ, 25 Gin Ling Way, Chinatown

STEVEN: Our friend Ella Black didn't take drugs back in the day, so she actually has a good memory; her brain's not pickled like most of ours. And she journaled a lot, and she found the journal entry for our first show at the Hong Kong Café, when we were opening for Black Flag. According to her journal, that's the night that David Bowie showed up to the Hong Kong Café; this would have been Lodger-era Bowie, him just cruising LA, checking out the punk rock scene. I’ve always thought Bowie was in Chinatown because he was a fan of Asian women and was just cruising bars—but then he unfortunately got noticed by a bunch of punk-rockers who basically would've taken a bullet for him. And they just vibed him out of the space immediately.

Everyone was keeping it cool at first, but then Craig Lee from the Bags, and later of Catholic Discipline and then an editor at the LA Weekly, eventually broke the silence. He went over to Bowie and let it be known that he and everybody else in the room loved him, and he asked about doing an interview. Bowie made his immediate exit, of course; everybody was very angry at Craig for that. Anyway, one of the saddest regrets of my life is I never saw Bowie play live, but the weirdest thing is there's a really good chance that he got to see me play live that night—when I was 12.

POSEUR, 7154 Sunset Blvd., Hollywood

JEFF: (The original) Poseur was in an old, old house that was on East Sunset, and it was the first kind of punk-rock clothing store. It was run by this British couple who were the first people to sell Crazy Color and clothes from England. We'd go there as part of our trips to Hollywood. But Poseur, at that time, was on a very prostitute-heavy section of Sunset, so our song “Standing in Front of Poseur” was about that.

STEVEN: It was an observation. We were making an observation about the working girls that were in front of our favorite punk-rock store. And it's somewhat moralistic. I don't know where we were coming from, entirely.

JEFF: The song is not long enough to really resolve that.

GUARANTY BUILDING, 6331 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood

JEFF: It’s now a Scientology building, but before that, this was Louella Parsons’s office. That's where she ran her office of terror. We used to rehearse there; Paul Roessler was renting it from this weird old dude who had a band called the Avery Dalton Combo, so we kind of sub-rented from Paul downstairs and would have that whole building to ourselves at night. It was like a Raymond Chandler novel. I just saw this 1964 art film of Terri Garr go-go dancing for seven minutes on Hollywood Boulevard, and she bursts out of that building. You can find it on YouTube; it's incredible. And that was our playground.

STEVEN: It's just one of those classic Hollywood buildings, and it was essentially abandoned at the time. We rehearsed in the basement in ‘84/‘85 and had the whole building to ourselves.

JEFF: We’d do late-night rehearsals and hang out all night, running around. We literally had keys to the whole building. And right before we stopped, someone hired this woman, Trish, to do a Hollywood mural, like of the history of Hollywood. We we’re in the lobby hanging out with her; she would come at three in the morning. The Scientologists now boast about this mural, like it’s a tourist attraction you should visit and see for yourself.

CAVERN CLUB, 6419 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood

JEFF: This was [Bomp! Records founder] Greg Shaw's ‘60s revival club, down the street from the Guaranty Building. It was amazing, because it was all kids and bands and fans that only specifically dressed like and played the music of 1964 through 1966—nothing past that was accepted in this weird bizarro-land. But we were friends with a lot of those bands, so for some reason, we got a pass. And this is where we recorded what we called in our book “the worst album ever made” with Sky Saxon, “Private Party” Live at the Cavern Club. We were bootlegged by Greg Shaw, who was kind of a hero of ours, but he didn't tell us that we were being recorded for a live album.

STEVEN: That record was a weird combination of enthusiasm and disappointment.

JEFF: Sky refused to do any kind of rehearsing with us, and we were trolling the audience by doing Led Zeppelin and Runaways covers with Sky Saxon onstage. And we didn't have the bowl haircuts, we didn't have the ‘60s clothes. It was kind of a crazy event. The record cover is a picture of Rodney Bingenheimer looking like he's in mourning, and it's just the most confusing record I've ever heard. But I don't know that it's the worst album anymore; I've kind of changed my opinion. I just remember the only time I ever saw it in stores, it was in the secondhand section at Aron’s Records for 35 cents, and that always burns into my head. But when we first started touring Europe, people would bring it for me to sign. I'm sure that it's a collector's item worth much more than 35 cents these days. Maybe we should do a remaster now. With these whole Peter Jackson, AI-type remixes, you can take a bad-sounding mono tape and separate all the instruments; I bet it would be incredible if we did that with this album.

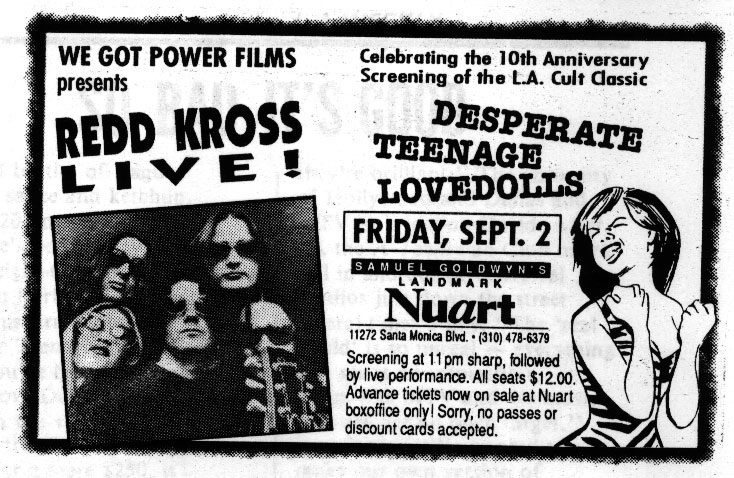

NUART THEATER, 11272 Santa Monica Blvd., West Los Angeles

JEFF: Pink Flamingos was a huge, giant influence on us. Seeing that movie for the first time was a revelation. The Nuart was a revival theater, so we got the chance to see Desperate Living, Female Trouble, and that was a very, very big part of Redd Kross. John Waters was such an inspiration, because he took what he did very seriously, regardless of how insane and bizarre it was, and you didn't need to have a million dollars. It was very inspirational on a creative level for us. I even tape-recorded Pink Flamingos at the Nuart. I brought a tape recorder and bootlegged it, and we used to listen to it. I think I still have that cassette.

STEVEN: I remember you'd always scour the LA Weekly or LA Times for club listings and see what's going on, and if there was absolutely nothing worth investigating, then we’d just go to the Nuart and watch Pink Flamingos again.

VIDEO ARCHIVES, 1822 N. Sepulveda Blvd., Manhattan Beach

JEFF: This was the only place to find weird movies, some of the first movies to ever come out on VHS, like Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and weird horror films. They’d put their bootleg tapes on the shelf, like all these Hullabaloo and Shindig! bootlegs. It was another kind of creative paradise for a while. I tried to get a job there and I didn't get it, and then next thing you know, Quentin Tarantino has my job! I went there a lot because one of my best friends also worked there, Chuck Kelley, and I'd chat with Quentin about movies and get into these crazy, very rabbithole-ish conversations. So he got to know us a little bit, and he put us in some of his early scripts.

In Reservoir Dogs, there’s a famous scene where they're discussing the Madonna song “Like a Virgin” and what it really means; that was based on a conversation that Quentin and I had, and he wrote it down. I didn't know that at the time, then I heard from Roger [Avary], this guy who worked there and was also a film director: “He took that whole thing from you!” I just thought it was genius and great, and just what writers do: If you can snatch a piece of something, you do it. Another a fun fact is when Quentin wrote the script to Pulp Fiction, he originally had in the script that Redd Kross’s [cover of the Bewitched song] “Blow You a Kiss in the Wind” opens up a scene or something. But then after he started making the film, I guess the recording didn't really meet the fidelity standards he needed. But when Quentin later hosted SNL, he sang our version. So, there you go.

BEVERLY HILLS FLATS, Beverly Hills

JEFF: We were a Beverly Hills band for seven years, thanks to the sponsorship of Dave Naz, the artist and photographer, and his mother, Maxine Nazworthy. They let us rehearse at their house, and that was the center of our scene for many, many years. We’d hang out and rehearse until really late, then get in the car and go to the all-night diner Larry Parker's, where you would see people like Nicolas Cage. Steve Martin, Bob Dylan, Buddy Hackett, and Lucille Ball all lived in the flats. We got into a lot of mischief during that time; we became tight friends with the Pandoras, right when Kim Shattuck joined, so they were our nighttime buddies. I dared [Pandoras keyboardist] Melanie [Vammen] to knock on Bob Dylan’s door and ask if she could borrow a cup of sugar, but she wouldn’t do it.

STEVEN: And then there was Jeff’s Michael Jackson sighting…

JEFF: Yeah, that was down the street at Lucille Ball's house. We used her house as an exterior for a shot for our movie Lovedolls Superstar; we just guerilla-filmed. I’d quickly walked through her yard, and then this car pulled at the stop sign, and it was Michael Jackson in a beat-up, mid-‘60s Mustang. I just said, “Hi, Michael!” And I had this Gene Simmons makeup that was all melting off my face—you have to see the film to understand why—and he just said, “Hi!” And then he drove off. And no one would believe me. They're like, “Why would he be driving that car? That's not Michael Jackson! You're high.” But I am positive it was him, because later when Moonwalker came out, Michael talked about how one of his favorite things to do was to rent a car from Rent-a-Wreck and drive around town. I know it was him; I mean, his window was down and I was standing like five feet from his face. But it was just one of those moments where all my friends were just out of sight and just wouldn't believe me.

STEVEN: I'm sure Michael knew what Gene Simmons makeup looked like. He probably got the reference.

JEFF: He didn't seem confused.

photo by Alison Martino

RAINBOW BAR & GRILL, 9015 Sunset Blvd., West Hollywood

JEFF: We always thought of the Rainbow [as immortalized in Redd Kross’s 1987 song “Peach Kelli Pop”] as a kind an open-air zoo. Remember those old zoos like Lion Country Safari, where you would drive through the open savannah and see animals in a wild setting? We would drive there during the height of the Poison era and watch people freaking out, like girls crying and fighting each other while someone's handing out fliers. I don't know why it was so fascinating.

STEVEN: Lemmy was always warming a bar stool there. John Entwistle was always there. It's lasted many different eras—I've been to family dinners there, even—but the hair-metal era in the mid-‘80s really seemed to be the Rainbow’s heyday. I also think of it as a wildlife refuge for hair metal and a certain era—like, it's safe for hair-metal people to roam free at the Rainbow. They're protected there. And you can go visit them.

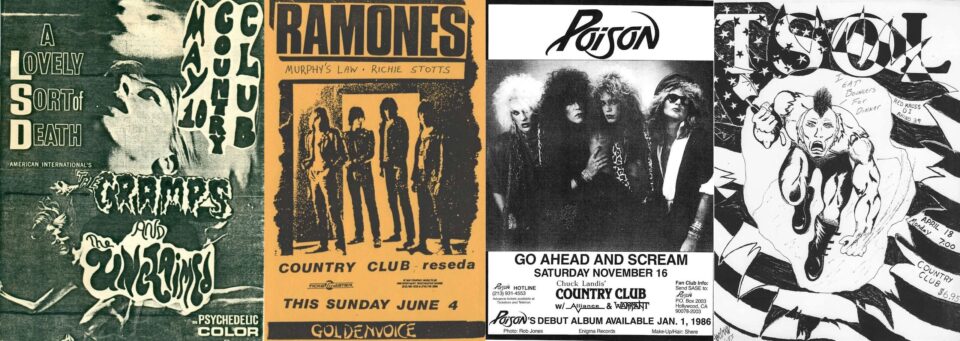

COUNTRY CLUB, 18419 Sherman Way, Reseda

JEFF: The first time I went here was to see the Cramps and occasional English bands, but by the time we got to play there, it was the early, early, early days of the hair-metal thing. We were asked, “Do you want to play this show with Poison? They're really into the New York Dolls!” And we were like, “Oh, cool,” but when we saw them, they were more like Van Halen than the New York Dolls. They’d probably never heard the New York Dolls. So we instantly became territorial with them. I was very kind of territorial about things like that then—saying that you were into the New York Dolls or The Runaways, if you hadn't lived that life of pre-punk existence.

ENIGMA RECORDS, 20445 Gramercy Pl., Torrance

STEVEN: We used to crank call our record label. Well, we had the same record label as Poison and Stryper for a brief period, Enigma, and we’d call the label pretending to be various members of Stryper and Poison and try to create a rift between the two bands. It was so stupid of us, because we had the same product manager! We would call and say, “This is [Stryper guitarist] Oz Fox. I'm out on the road and I can't find our record anywhere! All I'm seeing is Poison everywhere!” And then we’d do the same thing pretending to be C.C. Deville.

JEFF: They actually caught us because we crank called this woman, Gloria Bennett, who was this classical opera singer who was voice coach to the stars, people like Exene, Vince Neil, Bret Michaels…

STEVEN: Some of the greatest singers in Los Angeles.

JEFF: It was a disaster. We pretended to be Michael Sweet from Stryper, and I left a message on her machine saying I was going to sue her for destroying my voice. She had a freakout, called Enigma Records, and played them the tape. And everybody knew it was us. We weren't really good at lying about it. We said that our friend Paul K from a band called Imperial Butt Wizards had stolen our Rolodex: “Our friend's really mischievous. We’re really sorry!” Then the lady said we needed to write apology letters to both the Stryper and the Poison organizations. Paul gave us the idea that we should write the apology letters on a tortilla, but we never actually did. There was never any foresight, which was the true brilliance of that kind of stuff. We also kind of became famous for hacking Corey Feldman and Corey Haim…

STEVEN: Their 976 line.

JEFF: They made the movie Dream a Little Dream, and it was like, “Call the Coreys and maybe they'll call you back!” I figured out how to hack the outgoing message so they would advertise it on MTV, but it would really be our voices when the kids called.

STEVEN: It was incredible how fast the Coreys’ audience was willing to dump them. One of our messages was like, “All you bitches just leave me alone!” and then the girls were like, “OK, Corey, if it wasn't for us ‘bitches,’ you wouldn't be where you are, asswipe! And quit ripping off Michael Jackson!”

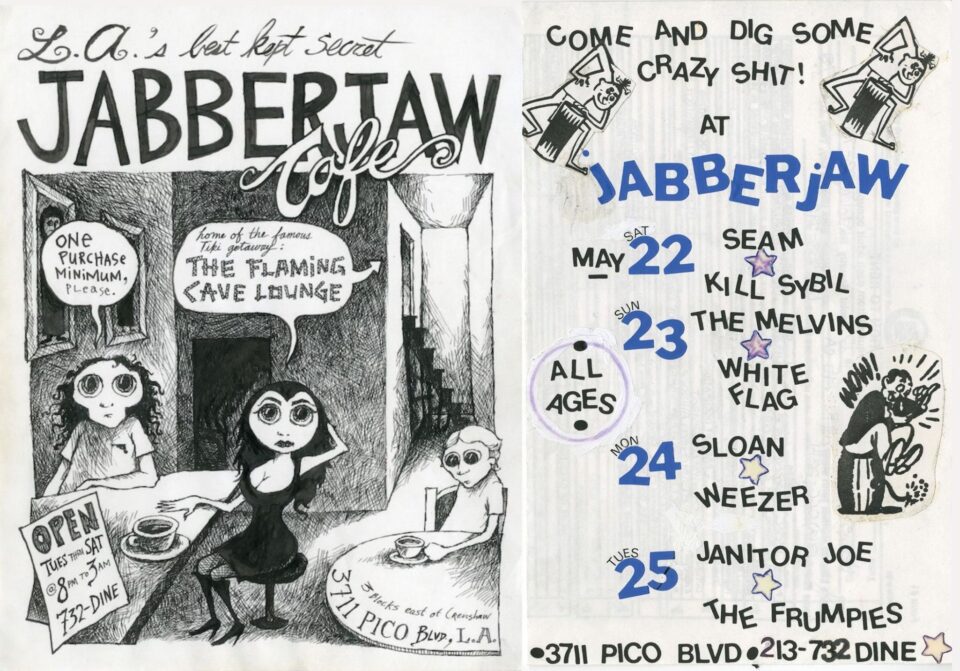

JABBERJAW, 3711 Pico Blvd, Los Angeles

JEFF: In the pre-Starbucks world, LA had a coffee house scene that was sort of a throwback to the beatnik days. I first used to go to the Pik-Me-Up, where Drew Barrymore worked briefly as part of her rehabilitation into post-teendom; in her book Little Girl Lost, there’s something about that being one of her first jobs. Then we’d go to Jabberjaw and play board games when it was a coffee house, before they even had shows. There'd be like 10 people, and that's where I first saw Courtney Love when she first burst into town. Then the indie scene started to explode and it became the cool place to play. The shows were insane there, because the place probably legally held 80 people, but it would be crammed. I remember when we played there, we wore all-white and I had a 1964 guitar that was kind of cherry wood, and after that show, it looked like I had blood dumped on me. All the finish came off my guitar and was all over my pants and my shirt, because it was so hot and everyone was so sweaty.

STEVEN: I asked my wife [That Dog frontwoman Anna Waronker] on our very first date at the Jabberjaw. It was at a Ben Lee show when Ben Lee was, like, 13 years old. I was filled with all this enthusiasm and love, remembering that I had once been a 13-year-old rocker myself. I was at the ripe age 26 or so. I just had this burst of confidence, so I asked her out. I heard she didn’t like typical dates, so I invited her to go guitar-shopping. We never ended up doing that, but it got the ball rolling.

BONAVENTURE HOTEL, 404 S. Figueroa St., Downtown Los Angeles

JEFF: For a couple of years, Beatlefest was huge here; the hotel had a giant ballroom where Beatles cover bands would perform. We loved The Beatles and they were very important to us, but the people at Beatlefest were more reliving this kind of nostalgia. So the second year we went, we had started a cover band called the Tater Totz with our friend Bill Bartell. It was kind of a Linda Eastman/Yoko Ono appreciation club; all of our friends were kind of in that cult, but only someone like Bill would've had the nerve to play Beatlefest. In those days, you couldn't even say, “Yoko”—it was a dirty word to those people! There were probably 1,500 people in the audience, and it was very ballsy to do this. The whole house erupted and the power was pulled, and it was just great. Oh, and Jimmy McNichol played percussion. It was “The Tater Totz featuring Jimmy McNichol.” I have no idea how Bill met Jimmy McNichol, but yeah, he put Jimmy on floor tom.

EAST WEST (OCEAN WAY) STUDIOS, 6000 Sunset Blvd., Hollywood

STEVEN: Our Phaseshifter album was mixed in the Pet Sounds room, which is Studio 2.

JEFF: When we finished Phaseshifter, we had a play-through with the lights off, just us. I think [Jeff’s wife] Charlotte [Caffey, of The Go-Go’s] was there. Juliana Hatfield was down the hall, and she came and listened to our album, so Juliana was the first non–Redd Kross person to hear Phaseshifter. I wonder if she still holds those memories.

STEVEN: Oh, no. I remember she was reading a book of French poetry and barely would give us a moment of her attention.

LAX, 1 World Way, Los Angeles

STEVEN: LAX is a real touchstone for my brother and myself. We grew up less than a mile from the southern-most runway, and we spent our summer days there, once we figured out that we could take the driveaway bus or long-term parking shuttle straight into the airport. Of course, we grew up pre-9/11, so there were no security measures and we could just roam around from terminal to terminal, imagining these exotic adventures. That was inspiring to me, so I have this sentimentality attached to the place.

JEFF: When you're going through America and you're in a more rural area, you'll find out that truck stops and gas stations are hangouts for local youths. So LAX was like our gas station. There was nothing else to do. We could either go to the local park or take the bus and run around the airport and get into trouble. We used to go on the top of the space-age restaurant and throw pebbles off of it, and we got busted once and had to run from security.

STEVEN: LAX was sort of like our Kum & Go. FL

Steven and Jeff McDonald circa 2004, Hollywood Hills, / photo courtesy McDonald Family Archive