At its simplest, and in real time, Ray Charles’ 1962 album Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music changed the sound of popular music for good. Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song,” Beyoncé’s Country Carter, and even the work of pioneering Black country vocalist Charlie Pride, whose first singles were released in 1966—each of these artists benefitted from Charles’ radical yet seamless leap into country at a time when any personal integration of Black America was, sadly, an impossibility.

But beyond cross-pollinating country music into R&B and pop, the already-successful Charles (he had hits with “What’d I Say” in 1959 and a Top 20 album with The Genius of Ray Charles that same year) brought country into the mainstream by recording the work of Nashville artist-composers such as Hank Snow (Charles’ cover of “I’m Movin’ On” predates Modern Sounds by three years), Don Gibson (“I Can’t Stop Loving You” became a pop hit for Brother Ray), and Curley Williams (“Half as Much”). For the sake of perspective, Hank Williams and Eddy Arnold each had country chart hits with, respectively, “You Win Again” and “You Don’t Know Me.” It’s Charles, though, whose soulful rendition of both of those tracks went the farthest commercially, aesthetically, and lastingly within a listening audience’s consciousness. Johnny Cash may have walked the line, but Charles crossed it.

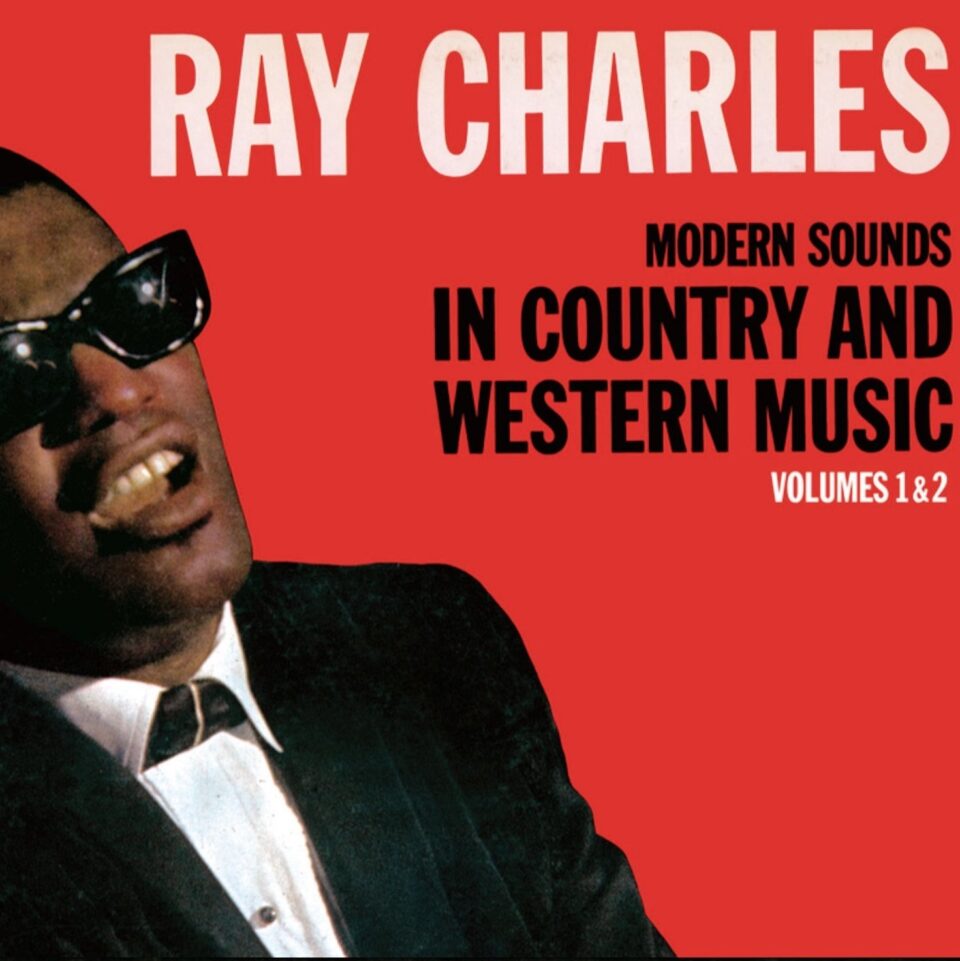

Ray Charles, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Vol. 1

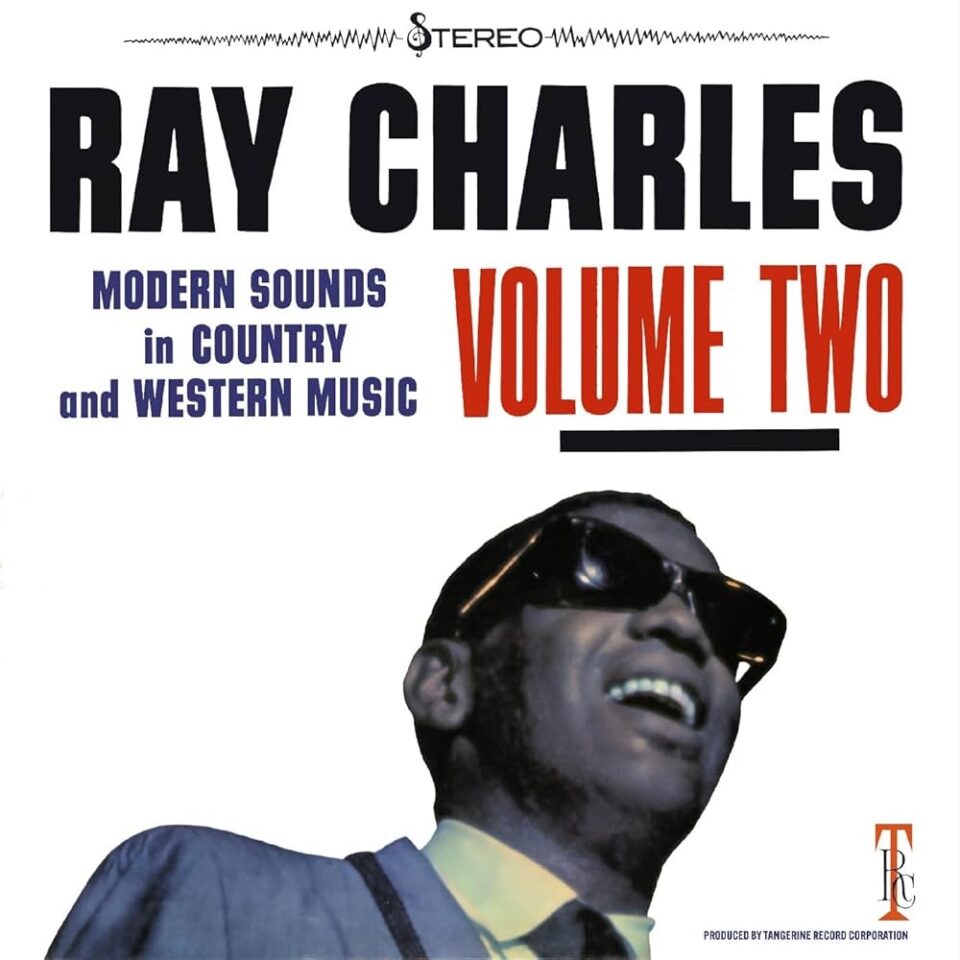

Remastered now for contemporary ears by Charles’ own Tangerine Records without losing the vintage warmth of their initial early-to-mid-’60s release, Modern Sounds and its second volume (also released in 1962) are their own coherently logical sonic continuum without forcing the issue (or, as author Daniel Cooper noted, Charles’ country forays “play like a series of intricate variations or one long meditation on the expansive qualities of music commonly described as the white man’s blues”). Produced by arranger-conductor Sid Feller, these two volumes are filled with melancholy and earthen, emotional lyrics and vocals, and find Ray at his most achingly earnest.

Rather than being his usual script-flipping vocal display of curving chords, shrieks, breaks, and hollers, Modern Sounds is pensive and evenly tempered while implicating Charles’ athletic emotional output in the subtlest of ways. While the first volume features Charles’ vocals nestled against the workings of saxophonist Hank Crawford, arranger Marty Paich’s plaintive strings, and a big band arranged by Gil Fuller and Gerald Wilson, Volume 2 had its vinyl sides split by the Ray Charles Big Band with the girl group The Raelettes on one side and a string section and the Jack Halloran Singers on the other.

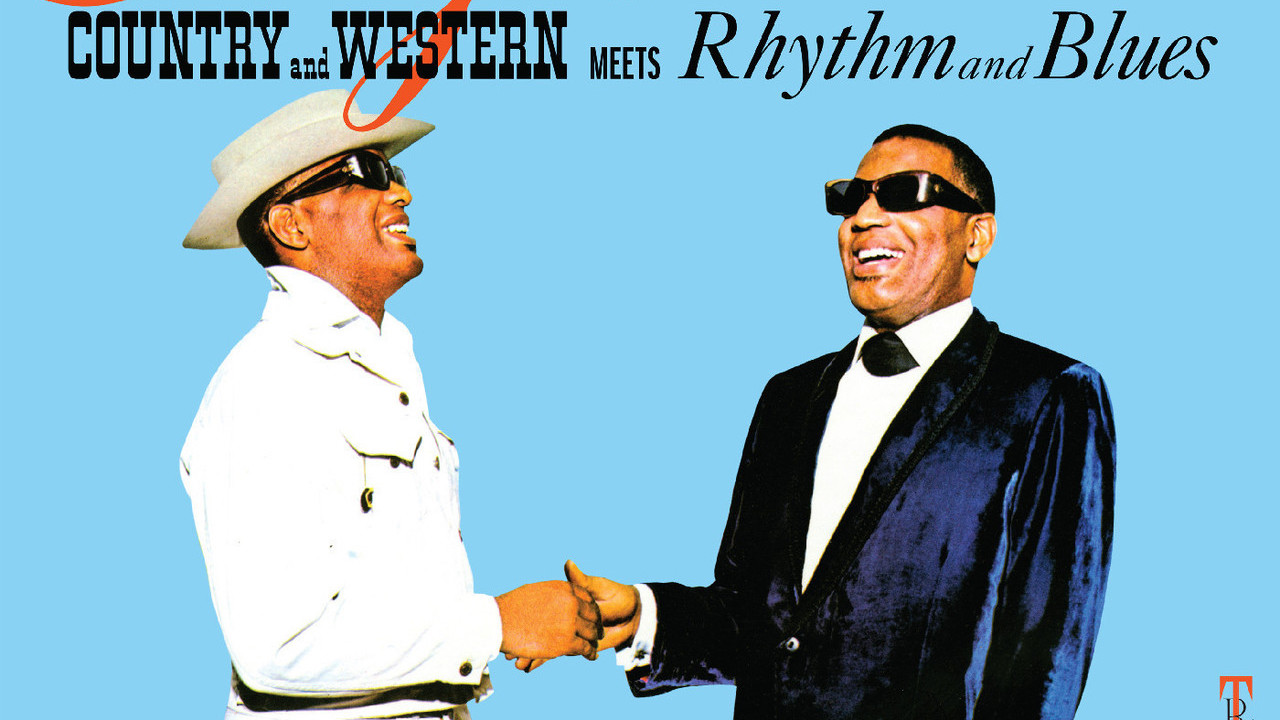

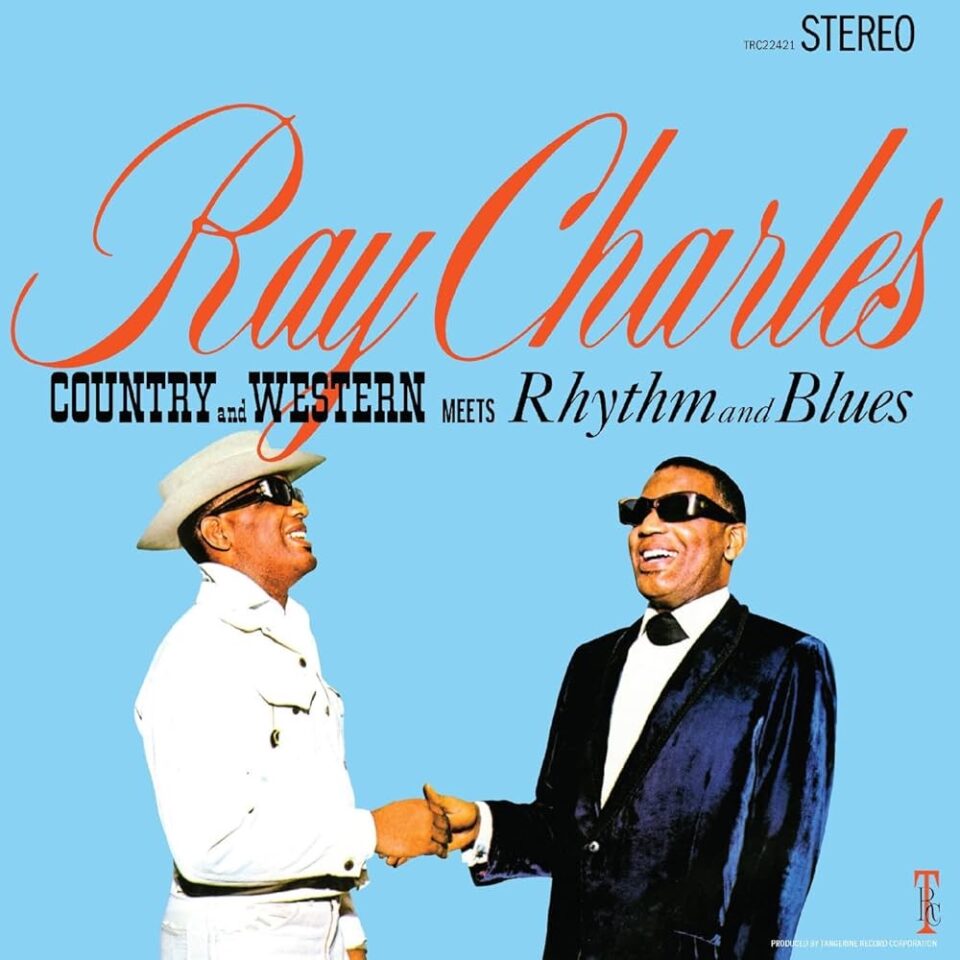

Building upon this foundation, 1965’s Country and Western Meets Rhythm and Blues was the first album Charles recorded in his own RPM International recording studio, and benefits from an even greater freedom from form than Ray’s initial country forays. His vocals are slightly more elastic, and his string sounds cinematic on his original country-soul composition “Please Forgive and Forget.” Charles’ co-write with Rick Ward, “Light Out of Darkness,” finds the vocalist using a gruff, rougher edge to his slow, swerving melody. After a record filled with tracks from country cousins Buck Owens, Harlan Howard, and Bill Monroe, Charles ends C&WMR&B with a brassy curve ball and his salty, verbal-tripping big band cover of Percy Mayfield’s “Watch It Baby.”

With that new start point and its freshly blended mix of darker, more sensual country and soul, Charles kept his sauce to an overheated boil with his infusion of gospel sounds on 1966’s Crying Time. Here, he has help from the weary, sexy comingling of electric organ and guitar from session men Billy Preston and Donald Peake, respectively, on the slow, simmering likes of “Let’s Go Get Stoned” and the prayerful balladry of “No Use Crying.” Owens’ pen again makes itself known on the string-laden, high country title track, as does Mayfield’s on the layered blues of “You’re in for a Big Surprise” and “You’re Just About to Lose Your Clown.”

The real kickers on Crying Time are switch-ups such as jazz saxophonist-composer Bill Johnson’s “Don’t You Think I Ought to Know,” played and sung (and screamed, at song’s end) as a string-soaked country ballad, with Charles slowing his boogie-woogie piano roll to a broken heartbeat; a groovy “You’ve Got a Problem” from big band leader Freddy James; and “Going Down Slow” from St. Louis bluesman Jimmy Oden, featuring skin-tight, after-hours jazz combo tone, again, with Peake and Preston.

Charles would again take on the sound and soul of country later in his career in 1984 with his Do I Ever Cross Your Mind and Friendship LPs (the latter renowned for its collaboration with Willie Nelson on “Seven Spanish Angels”), but nothing spelled out Ray Charles’ relationship to blending genre than these four genuinely innovative records. Some artists get to remake music once in their lifetime; Charles did so several times over, with these four albums representing his second or third shot at revolution.