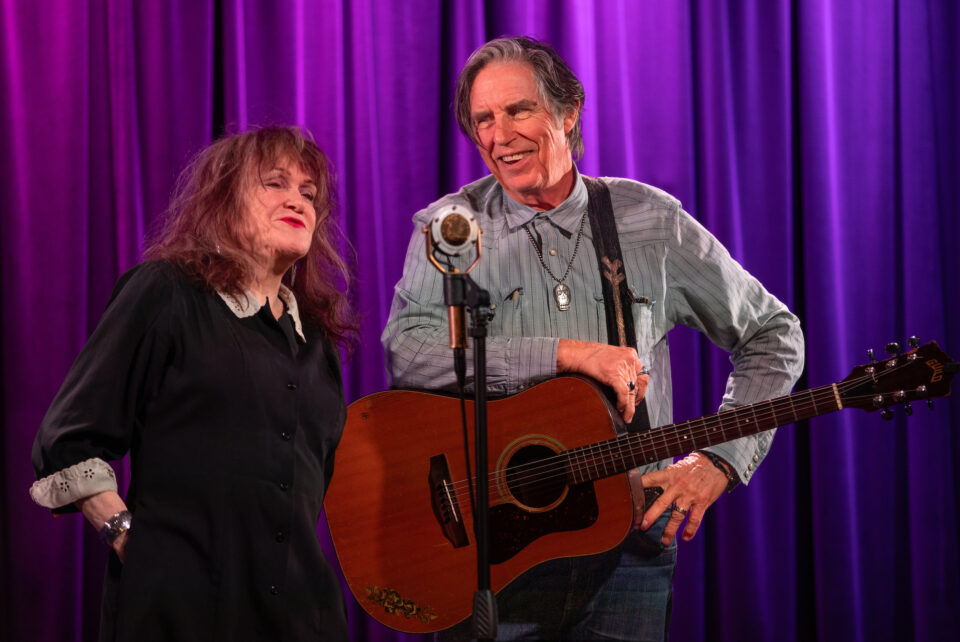

The troubadours onstage have devoted a lot of years and a lot of miles to get to moments like this one. Exene Cervenka and John Doe are singing alone tonight, standing behind a mic for a full house at the GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles, here to celebrate their decades leading the punk band X. But their songs during this short summer live set, with Doe strumming an acoustic guitar and his boot tapping an anxious rhythm on the carpet, are as much in the American folk tradition as the noisier edges of the first wave of LA punk rock.

The audience here has just watched a screening of X: The Unheard Music, the 1986 documentary that captured the band’s story at a creative peak with their original lineup. They were a revolutionary force then, with Doe and Cervenka singing in perfect, chaotic harmony, accompanied by the agitated, tumbling beats of DJ Bonebrake, and the rockabilly-meets-Ramones guitar whiplash of Billy Zoom. The event is timed to coincide with the August release of X’s new album, Smoke & Fiction, which the band announced would be the last of their nearly 50-year history. If things must end, then Smoke & Fiction is at least a satisfying farewell, drawing on the original sound and aesthetic found on the band’s first albums, the music seething and weird with lyrics usually bleak and literary, and based on experience.

Exene Cervenka anmd John Doe at Grammy Museum / photo by Steve Appleford

X is also pulling back on their touring life, cutting their live appearances down to major cities, festival dates, and one-off gigs. They closed out 2024 with their annual Xmas shows leading up to two nights at The Observatory in Santa Ana. This year will be their last of normal touring, including a May cruise hosted by Little Steven’s Underground Garage, joining Social Distortion, L7, and others. “Van tours are very, very hard, especially when you’re in your late 60s and early 70s,” Cervenka says. “That’s not a good time to be climbing in and out of a van with your suitcase and going to the Holiday Inn Express every other day to a new town.”

Even so, as the singer sits backstage before her performance over the summer, she’s still filled with nervous energy. Wearing a black dress with a white collar, she frequently gets up for coffee or to move around the room, then rests her head on the table before standing up again. Sitting calmly beside her is Doe, dressed in jeans and a gray Western shirt, a silver medallion in the shape of a skull hanging from his neck. Both of them seem content to let Smoke & Fiction represent their final major work as a band. The songs, as always, are autobiographical. “Even if you’re taking a newspaper story and writing a song inspired by that, you have to relate enough to it personally to [channel] the feeling and heart that makes it a good song,” says Doe. “You have to identify with that in some part of your experience.”

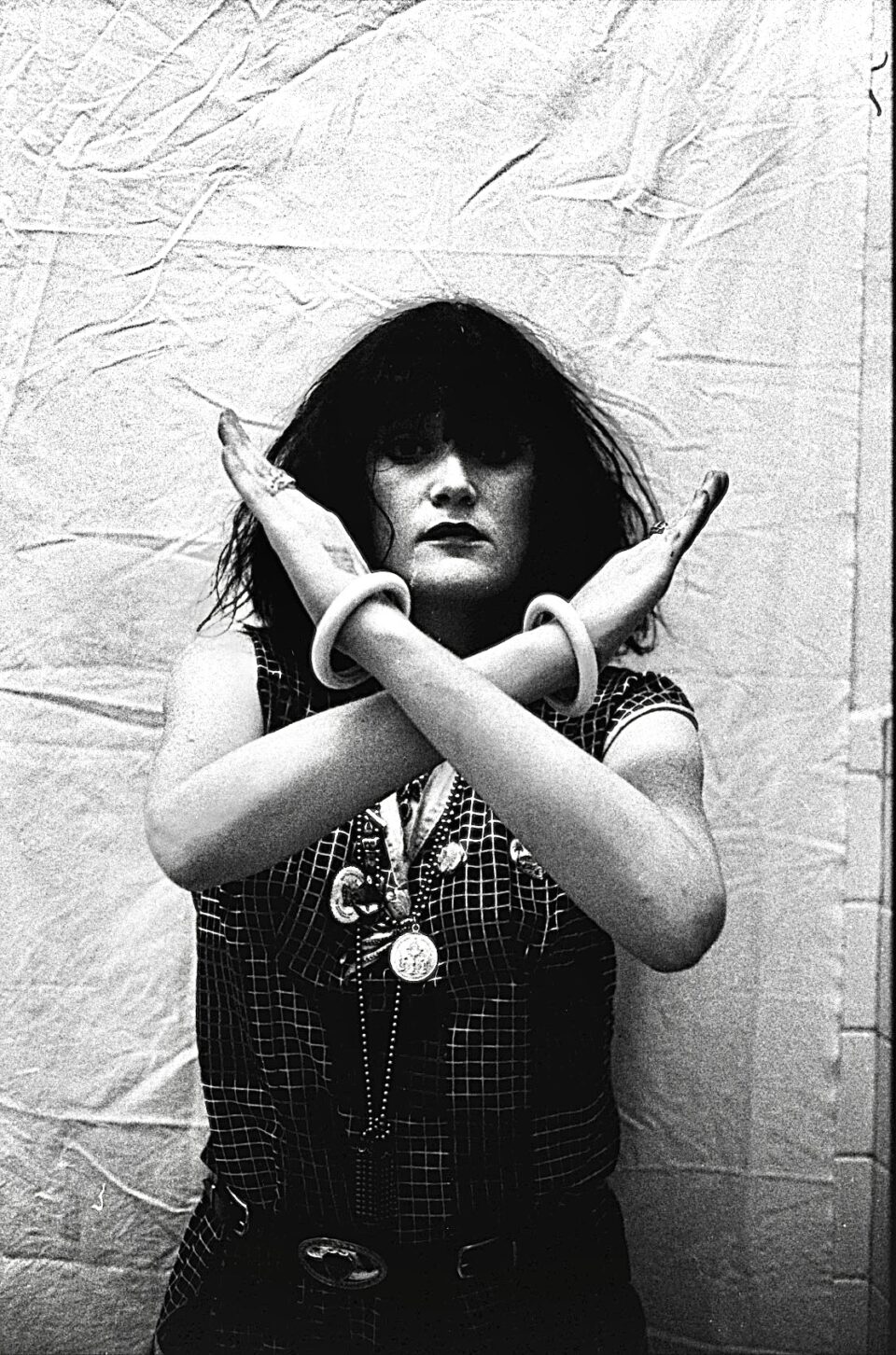

photo by Frank Gargani

On the record’s anxious title track, Cervenka sings, “Wrapped up tight in twilight / In a bed I am borrowing / My face turns to sorrowing / When I’m dreaming about tomorrowing.” The verse ends with a made-up word designed to capture a mood for the song that no existing term could (“It’s Louis Carroll; it’s inventing words and then owning them,” Doe says). Elsewhere, “The Way It Is” rides a spooky guitar hook, with waves of echoing twang. The lyrics were inspired by an outlaw country tour Cervenka and Doe were a part of, surrounded by old friends and comrades. “I saw my friends and they were diminished and it was beautiful and sad,” Cervenka recalls. “I was in the midst of the battlefield, painting the picture, the cannonballs flying,” adds Doe. “It brought up a lot of feelings of, ‘You’ve got to make peace, you’ve got to be good with what you’ve done and what you’re going to do.’”

The band recorded basic tracks at Sunset Sound in Hollywood for three days, finishing drums, bass, and some rhythm guitar ahead of schedule. They then worked on vocals, lead guitar, and everything else at the private studio of producer Rob Schnapf. The slippery guitar work on “Sweet ’Til the Bitter End” lands like a sonic cousin to the rockabilly-overdrive whiplash of the 1982 classic “Motel Room in My Bed.”

Making this final album was a two-year process from conception to final recording. Before going into the studio, several of the songs were road-tested on tour. The final result is not a mere echo of their past, but a continuation of their classic era, still vibrant in 2024. “I guess I’m resigned to [quitting],” says Bonebrake, in a separate interview via Zoom. “Of course I want to play forever, but I think it’s maybe time to call it quits, you know? I think we’ve got a good year in us, I hope. It’s a tough thing to do. It’s weird, ’cause I’ve been expecting it for 20 years. I’m 68 years old. I play with abandon. I’m very physical. But you don’t know how long that’s going to last.”

While Doe has settled in Austin, and Cervenka and Zoom live in Orange County, Bonebrake is currently the only band member still living in Los Angeles, where X not only found their mid-’70s birthplace but also their essential subject matter. Doe arrived after playing in bands in Baltimore, and Cervenka came from Florida with no band experience at all. “I believe in fate,” Doe says, describing how songs were created against “the backdrop of Los Angeles. What we felt at the time was a very disposable culture played into the velocity of what we created. It all seemed like, ‘Oh, we’re living in this soup, and it’s right here.’ Downtown [LA] was pretty scary then. It was deserted, like Wall Street used to be in New York. And everything was in a funny state of decay. That really piqued my desire for living a bohemian life.” Zoom was already in LA. He’d spent much of his career playing R&B and rockabilly, but heard something exciting coming out of Queens. “When I heard the Ramones, I thought, ‘Wow, I could do something with this,’” Zoom recalls.

“Back then, we were just trying to tear everything up and create something new. That’s what you gotta do.” — Exene Cervenka

photo by Edward Colver

X started in 1977 after Zoom put out a classified ad looking for a bassist and drummer. Doe was the second bass player to audition. He brought his new girlfriend along, who wrote biting, evocative poetry. The LA punk scene spawned not only X but The Go-Go’s, Germs, Black Flag, Circle Jerks, Minutemen, Fear, and indie labels like SST Records. It was a vibrant time in the city. “The film people were inspired by what was going on in music,” Cervenka recalls. “The journalists were inspired. The photographers were inspired. The bands were inspired, ’cause they were getting their picture taken, and people asked them to do crazy things. And fashion designers came out of that. It was just a current running through everything.” Doe adds, “People say, ‘What is punk rock?’ It’s your desire and determination to do something when somebody says you can’t or shouldn’t, and the freedom to do that. It’s like, ‘Watch this.’”

Like others in the scene, X was fueled in part by a desire to break beyond the pop and rock formulas of the 1970s. Cervenka was especially outspoken in her dislike of Fleetwood Mac, and it hardly mattered if she was wrong about that as long as it inspired her own songs. With time, her views have softened to a kind of admiration. “Now I’m like, ‘What was I thinking?’ These people are amazing,” Cervenka says. “I do have regrets about some of those ideas that I had then that were dismissive of other artists, because I think that everybody deserves respect. But back then, we were just trying to tear everything up and create something new. That’s what you gotta do.”

“We owe bands like Boston and Steely Dan and the Eagles a great debt,” Doe laughs. “If it wasn’t for them, you wouldn’t have youngsters like us saying, ‘This is bullshit, I’m tired of this.’ I still can’t listen to Steely Dan.”

X became a prolific creative force, releasing a new album each year from 1980 to 1983—four widely acclaimed releases produced by former Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek. Then came 1985’s Ain’t Love Grand, an album that alarmed fans and critics by leaning toward a more commercial sound. Produced by Michael Wagener, known for mainstream metal records with Accept and Skid Row, it led to their first broad mainstream airplay with the single “Burning House of Love,” which amounted to X with some of the rougher edges softened. “It got us on the radio, so that was a more pragmatic choice,” says Bonebrake. “And in a way, we all regretted it.”

By then, Doe and Cervenka’s marriage had also split apart, and they were now writing songs less as a duo, which reflected in their lyrics. When the album failed to beat the sales of previous records, Zoom quit. X continued with a new lineup that included guitarists Dave Alvin and Tony Gilkyson, and together they bounced back with a new Americana-flavored direction with the 1987 album See How We Are. The record included “4th of July,” written by Alvin for the band, and might have marked a new expansion of their scope with the addition of a third accomplished songwriter—but then he left, too.

photo by Gary Leonard

“People say, ‘What is punk rock?’ It’s your desire and determination to do something when somebody says you can’t or shouldn’t, and the freedom to do that. It’s like, ‘Watch this.’” — John Doe

The records stopped coming, with only one grunge-era release, 1993’s Hey Zeus!, that was part Americana, part hard rock. Zoom returned in 1998 and X was back to its original quartet, sounding great as ever onstage, but anyone hoping for new music was disappointed. X became strictly a live act. Yet onstage, they’ve always delivered. In 1998, with Manzarek back producing, they recorded two versions of The Doors’ “Crystal Ship” for an X Files movie, and in 2009 released a holiday EP. That was it until Alphabetland 11 years later.

But affection for the band lived on, long after their initial arrival, as X discovered when a free concert in 2013 drew a packed crowd of many thousands to Pershing Square in the heart of Downtown LA. It left an impression. “That was insane,” Bonebrake remembers of the crowd. “Exene has the same feeling that I have. She goes, ‘I expect to show up and no one will be there.’ I’m always surprised, and it’s always heartwarming. Like, ‘Wow, they’re coming to see us? Is Led Zeppelin playing after us? Is Pearl Jam on next?’ It’s a great feeling.”

The acclaim that greeted X in their early years ultimately led to frustration that the band couldn’t reach a larger mainstream audience. Decades later, the irony is that many acts that had hits in the ’80s are long forgotten now, while X remains an attraction. “I’ve been incredibly lucky for most of my life—I didn’t always appreciate it at the time, but I’m still here, still making a living, playing music,” says Zoom, now 76. He adds with a laugh, “But I don’t know why the bands I had before weren’t huge. I don’t know why X wasn’t huger, but I also don’t know why it was as big as it was. I just enjoy it, try to do the best I can.” FL