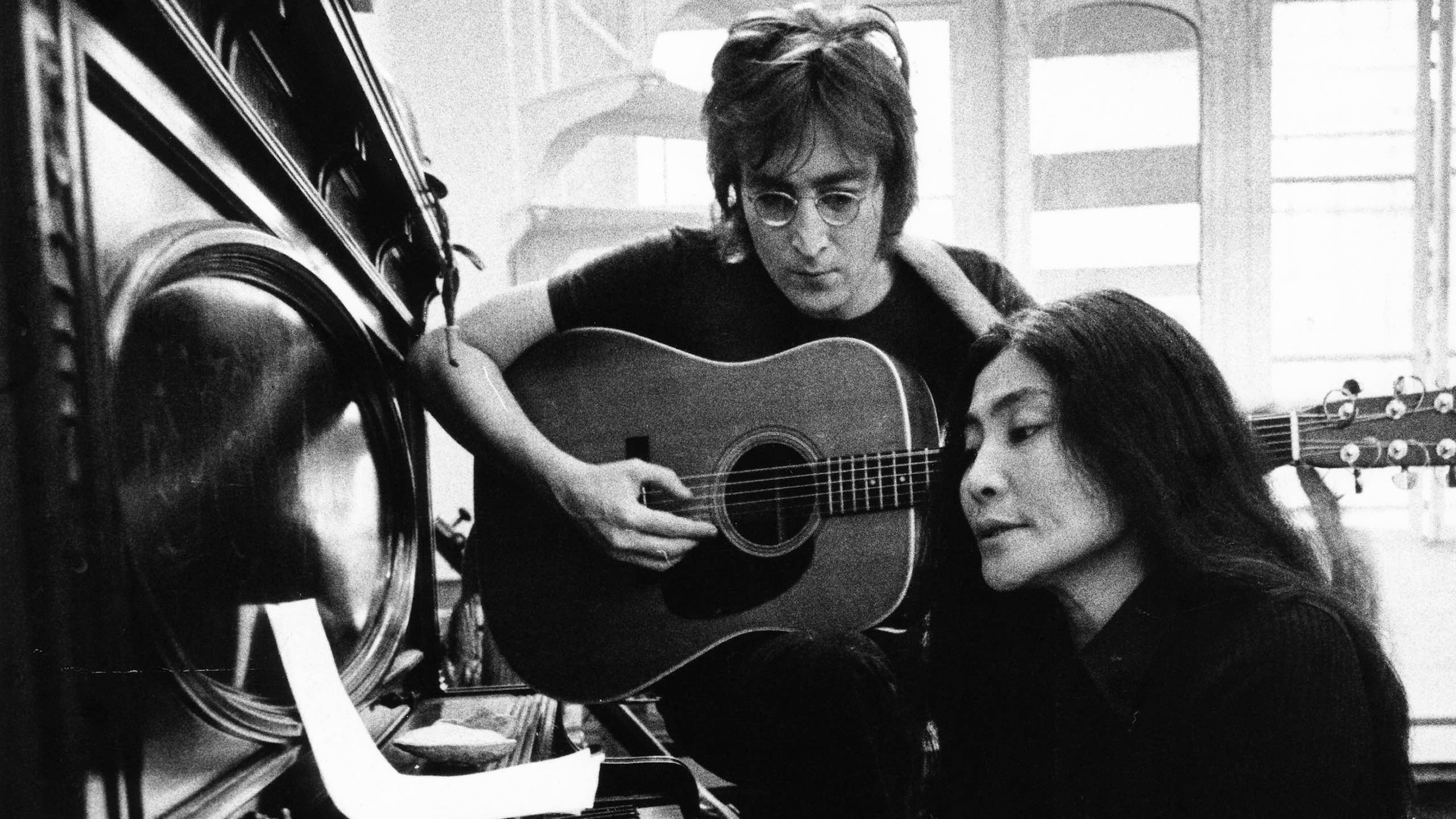

If you’re old enough to remember Yoko Ono beyond the abstract of the present, she was initially only seen as the woman in white next to John Lennon, the woman in black turtleneck next to John Lennon, the woman in camouflage gear next to John Lennon, the woman in nothing next to an equally bare-assed John Lennon. A lone Yoko Ono only happened, devastatingly, upon the murder of Lennon, a moment when we prayed to see her next to him. Before Lennon’s death, the trope of an ever-present Yoko wasn’t at all welcome. She was anathema; she was the shrew who broke up The Beatles by hypnotizing John away from the Liverpudlian mop-tops. She wormed her witchy way onto Lennon’s albums with her atonal banshee cry. She was allowed to make awful solo music solely because she was the wife, hanging on his name. She brought Lennon down long before a bullet did.

The mantles of misogyny and racism were forever filled with anti-Onoisms. But there were a fleeting few who knew that Yoko was a highly innovative visual artist who spun the Fluxus movement on her multi-mediated axis, a deeply intuitive post-classical musician and composer with operatic training, a kabuki practitioner, an avowed avant-gardist and activist, and a woman whose jarring pre-punk aggression inspired Sonic Youth, The B-52’s, Devo, David Byrne, Cyndi Lauper, RZA, and more in her wake. As an incendiary performance art, she confronted issues of cultural identity and gender, remaining unafraid to let people poke, prod, and cut off her clothes. Along with the musician Peaches reliving that 1964 performance, Cut Piece, in 2014, multimedia stage creationists from Taylor Mac and Karen Finley to the late Kathy Acker owe a debt to Ono’s work.

While many of us had to hide our copies of the concept-rich Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings, published two years before Ono met Lennon, all of the anti-Yoko memes, the music-business misogyny, the sonic intolerance, and anti-Japanese bigotry stops now. Author David Sheff’s Yoko: The Biography and director Kevin Macdonald’s One to One: John & Yoko—two newly released, right-setting works of non-fiction, one written, one filmed—have made it so that Yoko is set free from her Beatles-damning past. The pro-Yoko zeitgeist starts here. “It does feel as if things will start shifting in the ways that people look at Yoko,” says Sheff. “Although it’s still true that there are people who consider her the dragon lady who broke up the Beatles, robbed his creativity and seduced John Lennon away. I saw a bumper sticker not long ago that read ‘Still pissed at Yoko.’”

Sheff’s biography started with a friendship that developed when the young journalist, then aged 24, interviewed Lennon and Ono in 1980 for a Playboy feature published days before Lennon’s murder, one which found a frank Lennon making the claim that Yoko’s music was as important as anything The Beatles had recorded. Sheff recognized then that Yoko had been treated horribly by laypeople and entertainment professionals alike and marched forward making his pro-Ono case for The Biography by speaking with Fluxus collaborators and art world giants such as composer La Monte Young and printmaker Alison Knowles. “I made my inquiries to Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr and got polite, even terse responses,” says Sheff.

“Most of the people who condemn Yoko never heard Yoko. Besides, if she didn’t repel listeners during her concerts, she felt as if she had not done her job as an artist.” — David Sheff

As a multimedia artist of great depth and wily experimentation—a woman renowned and damned for her primal scream—Sheff puts every horrified holler into perspective by telling readers that it was joy and hardship that provoked Ono’s every screech. “She expressed all that was going on inside of her—be it ecstasy or the pain of the war she grew up through, the wars presently raging, the plight of the daughter she lost for decades due to her first marriage. Most of the people who condemn Yoko never heard Yoko. Besides, if she didn’t repel listeners during her concerts, she felt as if she had not done her job as an artist.” When she wasn’t repelling, Ono was working toward uniting, creating an aesthetic of peace and love before Ringo’s symbolic finger gesture, one based on Ono’s imagining a world different from the one she and her husband had protested. “Yoko truly dreamt of a world where people lived in peace,” says Sheff. “That was her thing.”

Scottish filmmaker Macdonald came to Yoko’s defense in a more circuitous fashion. Renowned for his Oscar-winning doc One Day in September about the 1972 murder of Israeli athletes, along with docs on Bob Marley, Whitney Houston, and the boxing Klitschko brothers, the director was handed the prized footage of Lennon and Ono's “One to One” benefit concert for the children at Willowbrook held at Madison Square Garden in August 1972. These shows were the only true, full concert performances by Lennon following his split from The Beatles in 1970.

What Macdonald built from that footage and purely archival documentary and interview material was a love letter to John and Yoko’s initial adventures in NYC and the couple’s residence in a cozy Greenwich Village apartment from 1971 into 1973. “They were out and about, walking the streets, appearing on TV talk shows, being covered by news crews, shooting their own home movies, recording their own phone calls,” says the filmmaker. “There was an amazing archive of material from this moment, something that never happens with them again.” What made that formidable 18-month period different from other formidable periods in the couple’s life is that this is “the John and Yoko after The Beatles and before the Dakota building,” says Macdonald. “They’re in tumult at a time when the country they’ve come to is in tumult, and they’re figuring out what to do with their lives.”

“We found all of these bits of audio from her talking about how The Beatles treated her and how the fans treated her, how she was made to feel as if she’d stolen their golden monument. I felt for her.” — Kevin Macdonald

Along with Lennon’s “utterly transfixing performance” throughout this 1972 concert, Macdonald believes that one of the big reasons that he took to this film was to reassess who Yoko Ono was, and is. “I wanted to humanize her,” says the director. “Looking at the archival material that came from the estate, Yoko is the most fascinating person, someone who John treats as his equal, a woman he admires creatively. I put myself in her shoes, too; what it must have been like to be married to one of the most famous men in the world. We found all of these bits of audio from her talking about how The Beatles treated her and how the fans treated her—people made voodoo dolls of her—and how she was made to feel as if she’d stolen their golden monument. I felt for her. I wanted the audience to feel for her—a mother who lost her child, stolen by her ex-husband, how she was impacted by that. John and Yoko came to America because of her and her life.”

At the end of One to One, Macdonald subtly shifts the energy and the emphasis of his documentary from their concert and his triumph to Ono and her POV: the first International Feminist Convention at the top of 1973. “By film’s end, John is there, the hanger-on. It’s all about her—her questioning about her life, her thoughts of suicide, the line in her song ‘Age 39 (Looking Over My Hotel Window)’ where she sings for Kyoko, ‘She haunts me in my dreams, and that’s saying a lot for a neurotic like me.’”

For someone who was, in Ono’s words, “first the bitch, then upgraded to a witch,” Macdonald’s view was based on her reality, but by film’s end lands in regality. As it should be. FL