On albums and in live settings, songwriter, vocalist, producer, and baritone guitarist Kristin Hersh holds sway over a frantic compositional vibe with melodies and arrangements ragged and jagged, and a wild inner-monologue-like lyrical éclat that’s as stark and freestyling as Black Thought battling Kendrick Lamar. In person, that same monologue is more generously outgoing—despite the insularity of her psyche—and deeply, quickly, quirkily funny.

Such combination of the heady, the haranguing, and the hilarious is where the newest albums from her Throwing Muses trio with drummer David Narcizo as bassist Bernard Georges reside—Moonlight Concessions and its skeletal demos partner, Moonlight Confessions—solidly in opposition from Hersh’s folkish solo records and her other loud-ass trio, 50 Foot Wave, yet with occasional bleeds. Just because.

We spoke with Hersh after the close of her solo jaunt through Australia and New Zealand, but before leaving home again with the Muses for a set of May dates in Europe and the UK.

When you do something, it’s always a matter of 30 new songs spread across three separate recordings, and you’ve written a book to go along with it. And each song is smart and emotional, without being coy and histrionic. Do you ever tire of being the cleverest, most industrious person in the room?

That’s a lovely way to put it. It’s a yes-and-no answer: Yes, in that I know how to do it, and no, because the way that I do it is to completely remove myself from the process.

I get that.

And if anything goes wrong, it’s because I’ve gotten in the way. So I don’t know if that’s humble, but my process is to disappear. That’s because an inspired work needs a conduit, right? And a conduit can’t be just a mechanism where you’ve got all the senses working. That’s how you get to these inspired moments. But are you a reflection of that moment? That’s where you have to call yourself out. Are you stepping on that moment, or are you stepping into it, inviting others to be in it with you? I get stuck on the “inviting others” part, because I’m really shy. And because I’m a mammal and don’t like to be looked at [laughs]. But I love being alive.

So a song is an alive thing. My kids are alive things, books are alive things, a moment is an alive thing—if they’re all inspired. If my songs are not inspired, it’s because I felt bad for a moment, or I let something die through me for a moment, and those mistakes are unsharable. So my answer is yes and no [laughs]. Either way, I don’t give myself much credit. But I do know that I’m good at disappearing.

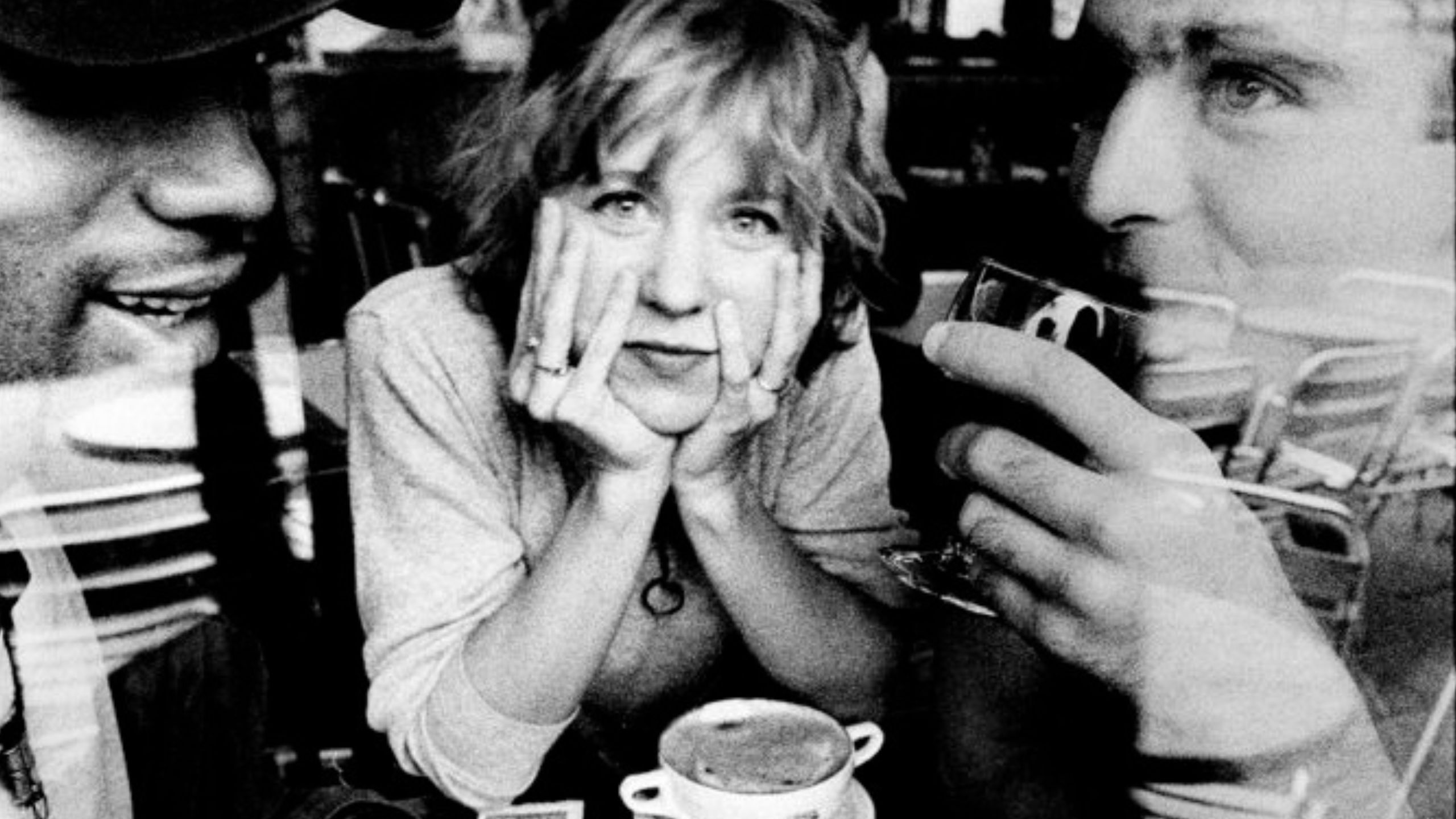

Kristin Hersh at FLOODfest 2023 / photo b Daniel Cavazos

Is your disappearing act as prevalent in your band work as it is in your solo work?

Yeah, because it’s just a song. A song is a sound body. I’ve been literally disassociated when I work sometimes. I do that because the song is using my life pictures, my life story. So it acts as a syringe, and I return to those moments, vividly. Have you ever seen a movie without its musical soundtrack? Sometimes it’s not as cool, right? My songs are my soundtrack. My life pictures are easier to take when they’re set to music. My son Bodie says that the happiest memories are the hardest ones, so my songs, that moment—I gotta be ready for that syringe. And I have to accept it, so they [Throwing Muses] do this gentling by making it all musical. Even with my noisier band, 50 Foot Wave—it’s a gentling experience to have my music turned into ocean waves. The mundane, scary stuff, as human as it can be, is still off-putting if we don’t have it set to the right soundtrack.

Is Throwing Muses a different set of colors than 50 Foot Wave or your solo material? Do the colors vary between past Muses records and this new one?

Most of the colors are chord-related, so, yes, Throwing Muses does have a distinctive set of chord progressions and colors, oddly. 50 Foot Wave is more of a melodic drive, like a storm, and I’m hiding all of its idiosyncrasies in its chordal relationships. The mélange of chords in 50 Foot Wave is epic.

So Throwing Muses’ colors are more subdued.

I don’t know how people relate to music without colors—don’t hear them that way, or think of them as such. Maybe I have too many bands [laughs]. It’s so much easier for me to color-code things. I just remember that, yeah, this song is burgundy and yellow, then it goes into tangerine for a minute.

In Muses, how do Bernard and David work within that color palette? Is there a discussion among the three of you? I mean, the songs are yours, but if they have blue, and you have yellow, you’re going to get green as the end result.

[Laughs] That’s great. I wish they would give me colors. They just accept my palette, always agree with it. It’s funny. I found the earlier Muses songs off-putting—still do. I love them, and am compelled to play them, but I didn’t expect anyone else to like those songs. Throwing Muses is not likeable; honest, yes. And it’s all love—we’ve never disagreed as we’re hearing what I’m producing. It either works or it doesn’t. And if not, we try something else.

“My songs are my soundtrack. My life pictures are easier to take when they’re set to music.”

Regarding its production, are you Throwing Muses’ best choice for producer, as it’s pretty much been you all along?

I get along with everyone, but it had to be me—I needed to not work with producers. These songs are my bones. It’s been decades now, too, that I’ve been doing it, and it’s an honor. It’s something I rejected at first. The studio process is not one that you can disrespect. You’ll cut the limbs off a song, and you can’t glue them back on and expect a song to live. To walk through that wall and see that myriad of color palettes available to you, and realize that it’s here where you can make a song shine—and there has to be a way to bring those energies together in real time and real space, and accept the human condition as a way that you’re actually dressing something up rather than let it be tattooed by a blind man. A song itself is a gift, but if you don’t help it walk into someone’s room, it’s never going to meet anybody. And that’s the ultimate goal: to have someone accept our song as their soundtrack.

Why the baritone guitar? You don’t use it exclusively, but you’ve used it a lot.

Because other guitars are too high. I tune the others down to C sharp and the baritone to B. Plus, the strings wriggle around in a very attractive way, and it’s got a nice mushiness and percussiveness.

When and how did the songs of Midnight Concessions have their genesis—baritone guitars, color-coded tracks, and beyond?

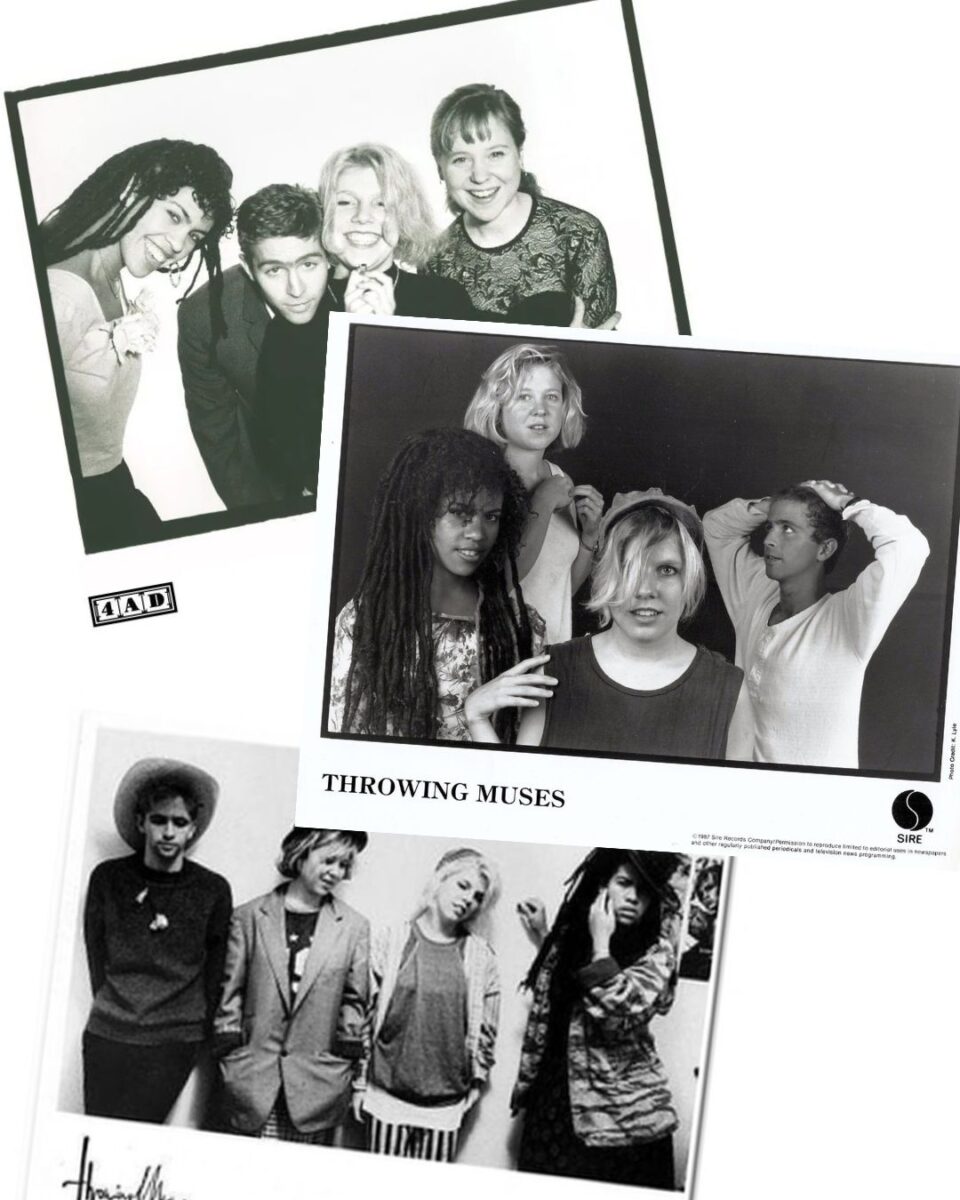

“Drugstore Drastic” came first. I was parked here in New Orleans, initially, and the only guitar in the house was this classical one. If a song is in the room, it’s an energy, a vibe. I’ll play whatever instrument there is to get it out. And the songs sounded very sweet. More than that, they sounded like songs that Throwing Muses used to play when we were 17. It was a what-the-hell moment, as if I was having a midlife crisis. Those were the songs that Ivo [Watts-Russell], the British president of my first label [4AD], actually took off the first Throwing Muses record as he wanted it to be arty and mad [laughs]. Those songs—the fun, American-sounding ones that Ivo hated—are what Throwing Muses are playing now. FL

Kristin Hersh at FLOODfest 2023 / photo by Daniel Cavazos