When San Francisco’s boldest purveyors of art-damaged, pre-punk, avant-garde music stepped into the chill of Eskimo—an album where windy, synthesizer-derived ambience turned into a haunting, icy backdrop for their skronky homemade instrumentation and faux-Inuit chants—it may have seemed like just another fit of pique to fans of The Residents. Only five years into their career as an anonymous quartet by the time of the album’s release in 1979, the collective had already become infamous for their rabid, freak-factoring unpredictability.

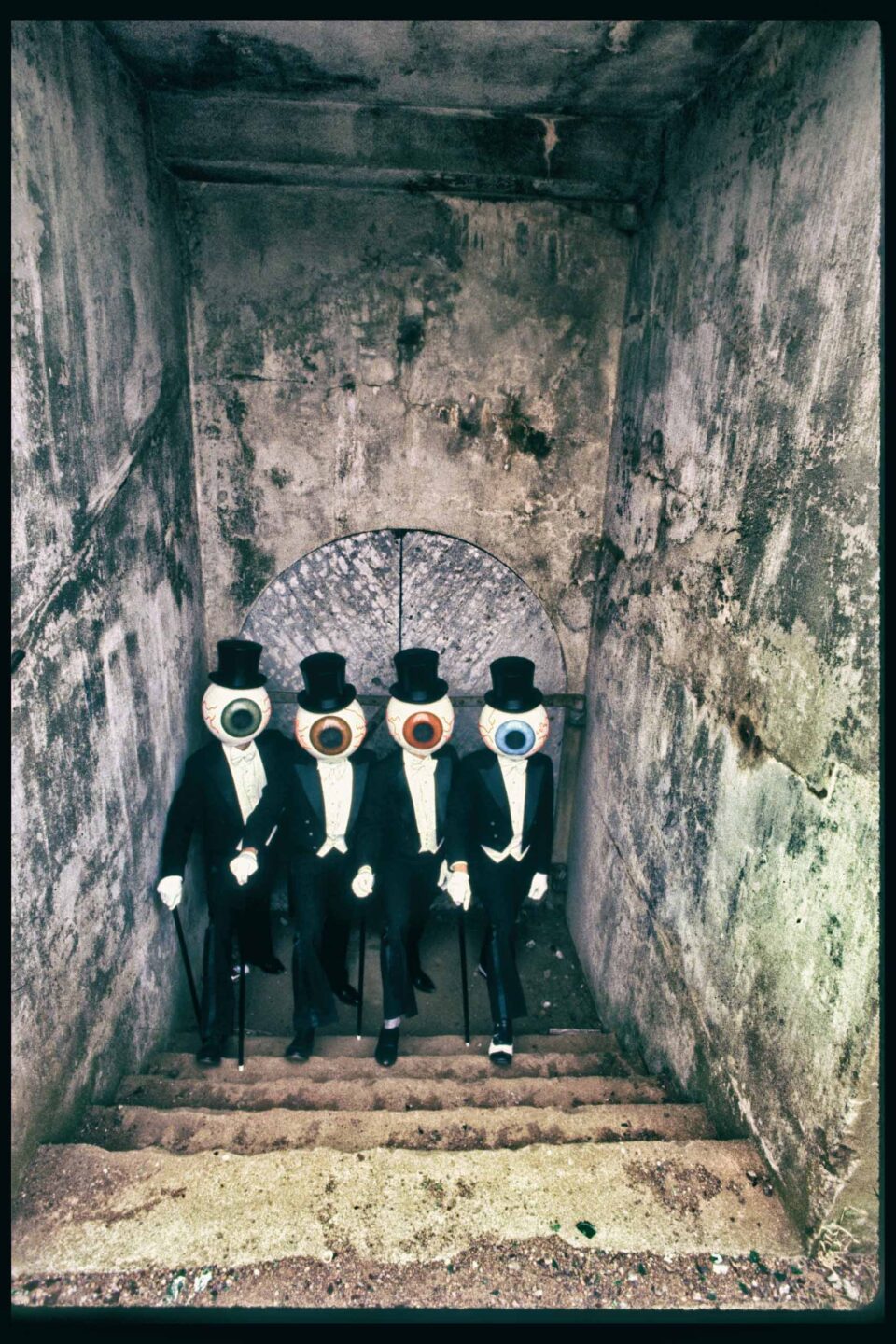

After having their demos rejected by Frank Zappa’s label for being too weird, the band announced themselves with their thesis statement on their 1974 debut Meet The Residents before craggily cat-calling their way through a mix of “semi-phonetic” interpretations of Top 40 rock and soul hits from ’60s radio on 1976’s The Third Reich ’n Roll. They attempted a three-sided album and created an independent space to release their music and that of fellow avant-garde music-makers with Ralph Records. It remained unknown as to who played what, and what their names and faces were through a series of cultish-looking homemade costumes.

All that, and still, Eskimo was their own monster epic, offering up its own unique challenges—a project whose particular live envisioning would have to wait nearly 50 years to live on stage, starting at Los Angeles’ Exoticon on June 7. “Well, it’s a good time for it anyway,” says Homer Flynn, The Residents’ de facto spokesperson about the live reconvening of the Eskimo aesthetic on stage. Since 1974, this gravelly sounding mouthpiece has additionally doubled as the band’s manager, costume designer, and, very possibly, an instrument-playing member of the ensemble.

Though Flynn is highlighting Eskimo—an album newly revived with several rare remixes and added track iterations, courtesy the Cherry Red label—The Residents only just released yet another new album, a decade-in-the-works metallic opera, Doctor Dark. Their intoxicating 1980s series of classic cover albums—featuring songs penned by James Brown, George Gershwin, Hank Williams, John Philip Sousa, and Ray Charles, along with unreleased interpretations of compositions by Sun Ra, Lou Christie, and Buddy Holly—have also been compiled by Cherry Red as the American Composers Series, planned for release later this month. There’s even a lost Residents original track, “Burning with Desire,” to be found within that re-packaging.

“The Peekaboo Gallery people putting Exoticon on have a tiki gallery in Pasadena that features camp artwork from the 1950s and 60s,” notes Flynn about the invitation for The Residents to play their chilliest album during this multi-media adventure. “Now, Eskimo isn’t exactly tiki. But Exoticon is about the exotic. And upon reflection, while not a direct fit with the heat of exotica, it makes for a nice tangent.”

If any ensemble knows anything about all things tangential, it’s The Residents. Like the romanticized version of island culture that all things exotica and tiki represent (think bachelor-pad lounge music makers Esquivel and Martin Denny), The Residents’ Eskimo was crafted as a romanticized, avant-garde envisioning of Inuit culture within the frozen perimeters of the Arctic Circle. Flynn states that Eskimo was intended by The Residents to be the follow up to 1977's Fingerprince album. “The Residents were kind of into what people used to call ‘ethnic music,’ and wanted to do their version of it,” notes the spokesperson. “But they didn’t want to jump on a bandwagon or repeat something. They didn’t want to do something inauthentic, either. So they went for something that they figured no one would know anything about—which, of course, gave them free rein.”

In reality, like much of their music (e.g. 1980’s Commercial Album being anything but what its title suggests), The Residents were satirizing the overall ignorance of those failing to recognize the foibles in musical appropriation while offering their own commentary on how Indigenous cultures were (badly) treated. To do this, The Residents penned a series of goofy, pseudo-ethnographic texts and melancholy Inuit musical interludes using their own homemade instruments, all of which pretended to be traditional Eskimo lore passed down from generation to generation. The low moaning and high squealing chants they crafted to sing these historical documents of Arctic life? All made up. But not easily made up.

“It took The Residents three and a half years to make something that was satisfying to them, fully,” says Flynn of the band’s experimental recordings. “They made short pieces, painstakingly, little by little. It wasn’t until they came up with an idea, totally based on sound: an Eskimo band with wind being as important as the music. They weren’t trying to make what would be the first of their ambient soundscapes, but that was certainly a result of their experiments.”

And the jibberish of Eskimo and its wall-to-wall textured, tactile language touched on the very thesis statement that fired up The Residents in the first place: the Theory of Phonetic Organization. “With that theory, words are put together more in accordance with how they sound than what they mean, in opposition to any real content or context,” says Flynn. “In their minds, words such as ‘kookabook’ sounded more…Eskimo-ish. This allowed them a certain level of free association, absurdity, and play. And they loved that.”

Nearly four years into their sonic experimentation, their wind-chiming, their kookabooking, and their wooly travels along an imaginary Inuit path, The Residents finished Eskimo—an album that, for a band who sounded like nothing else, doubly sounded like nothing the quartet had ever made—or would ever make. “They blindly stumbled along a trail until gut feelings and confidence told them that they had arrived,” says Flynn about The Residents most icily anomalous work. “They opened a door with Eskimo, and countless other doors inside of doors. In fact, I think that they did it, closed the door, and never even tried to go back into that door again. Isn’t that curious?” FL