Bruce Springsteen

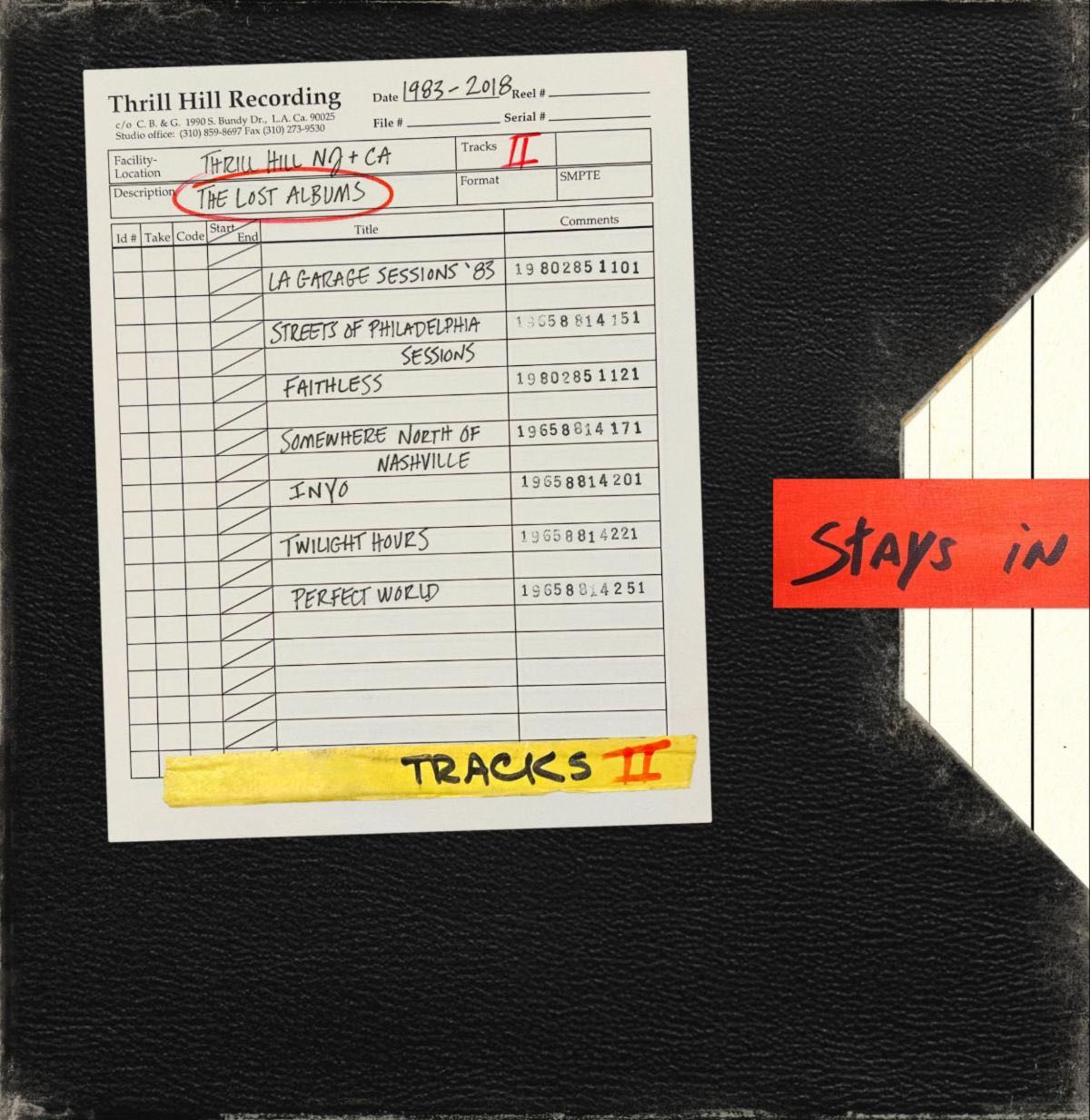

Tracks II: The Lost Albums

COLUMBIA

Fans of Bruce Springsteen wondering why relatively few albums of his were released in the 20 years between the marrow-spare and spine-tingling Nebraska and the forlorn-to-euphoric The Rising now have Tracks II for their troubles. Subtitled The Lost Albums and staring down the barrel of Springsteen’s shelved moments of doubt as to their importance to his official canon, this new box breaks down seven well-framed sets of sessions that, more often than not, were designed as full albums based on different moods. This isn’t whim being set in stone, but rather stories and tones that Springsteen at one point felt strongly about—experiments with drum loops, mariachi, synth-rock, country, after-hours saloon song scintillation—then, for one reason or another, didn’t.

Consider it a way in which Springsteen changed outfits, only to see what sound and lyric best suited him. That’s not to say that he sought out fashionability with the albums that fill Tracks II (what could be fashionable about a modern-day Tijuana Brass–like recording of Inyo, anyway?). More haute couture than fleeting fit or off-the-rack, Springsteen tailored these musical moods and lyrical images to his usual brand of bruised romanticism, broken character study, and confused sociopolitics. Diving deep into its 83 songs, Tracks II is an exercise in excess, but of the very best kind: that though he wasn’t John Cage, Moondog, or even Alan Vega, Springsteen has always been more of an experimental animal than he’s ever been credited for. And yes, you will find yourself questioning his motives, tastes, and blind spots when you realize how good some of this box set is, retrospect and beyond.

Opening with LA Garage Sessions ’83, the package starts off by finding the space that opened up for the mythical full-band Electric Nebraska that the Boss finally admitted exists, and the grander, souped-up heartland roar of its immediate, canonical follow-up, Born in the USA. Spidery, spare vintage rock ’n’ roll and minor-key folk with a drum machine and a guitar, Garage Sessions songs such as “Follow That Dream” are the axis between Sun-era Elvis Presley and pre-hospital-bound Woody Guthrie.

To me, as a local, the entirety of his Streets of Philadelphia Sessions has mythic resonance and a gritty heartbeat, as Springsteen continued to examine the small synth-drum loop dramatic balladry that made the theme song to Jonathan Demme’s 1993 AIDS crisis film Philadelphia so damned lump-in-your-throat poignant. One of these sessions’ finest, “Maybe I Don’t Know You,” is as sumptuous a song about jealousy as “Streets of Philadelphia” was regarding haunted human frailty. Not long after, recorded around the same time as the moaning folksy The Ghost of Tom Joad, Somewhere North of Nashville is indeed the country side of Bruce á la Music Row with more teary balladry and honky-tonk heroes than an episode of Hee Haw. The Boss never met a soul-strung Johnny Rivers song he didn’t like, and the mournful “Poor Side of Town” shows no exception. If you’re any fan of Elvis Costello’s Nashvillian excursions, Somewhere North is for you.

While E Street violinist Soozie Tyrell takes part in Springsteen’s Nashville lullabies, much of the rest of his band—pianist Roy Bittan, guitarist-vocalist Steven Van Zandt, and drummer Max Weinberg—each take a piece of Perfect World, an album of big rock cuts recorded between 1990 and 2010 that compensate with live-Boss bravura what they lack in unifying vibe and nuanced lyricism. Is this album mediocre because it’s all rote Springsteen stadium-pleasing stuff or because it lacks poetry? The only track that has any inner life and metaphorical richness is ”If I Could Only Be Your Lover.” If any disc takes Tracks II down a peg, it’s this one.

Then again, Inyo lifts Tracks II up twice as high, with its Texacali border songs of drug trade drama and wronged romance, its soft mariachi brass, and its supple jazzy rhythms. Everything that Joe Strummer ever promises with the Mesclareos—with twice the haunted heart and Narcos theatricality—stands out here, higher than the rest of the box.

Could Springsteen have had another life as a late-night, lounge-hound crooner? That’s sort of the question posed by the 2010s-spanning Twilight Hours and its Western Stars/Jimmy Webb inspired track list, only here reaching back, in a fashion, to the lost cosmopolitan sounds of Burt Bacharach and Hal David and their noir-ish balladry. I won’t lie, stuff like “Sunday Love” and its moody, swaggering ilk are so shimmery, sad, and end-of-an-era subdued that it’s hard to know how serious Springsteen was, and what he hoped to achieve by ever releasing this.

Anyone who’s a fan of Springsteen’s most recent album and its slew of gutsy R&B covers, Only the Strong Survive, will have steeled themselves for the Boss’ Tracks II foray into windy singing and spiritual sway that is Faithless from 2005/2006. Springsteen has done gospel in the past—heck, every time he gets on stage with the E Street Band, it’s a revival meeting. But momentum-building moments such as “God Sent You” and “Where You Going, Where You From” are downright uptight, sacred, and lifted heavenward in a fashion that takes these soul scorchers into something more than merely spiritual. Like the lounge album, Faithless is a lot to take in, but worth the weird reward.