Filmmaker Alex Ross Perry clearly loves movies as much as he loved the video stores that once peddled them—those archaic anachronisms of the late 1970s through the late aughts. He’s put together a spellbinding, if flawed, documentary that offers insight into the human experience through the way these two institutions once intersected.

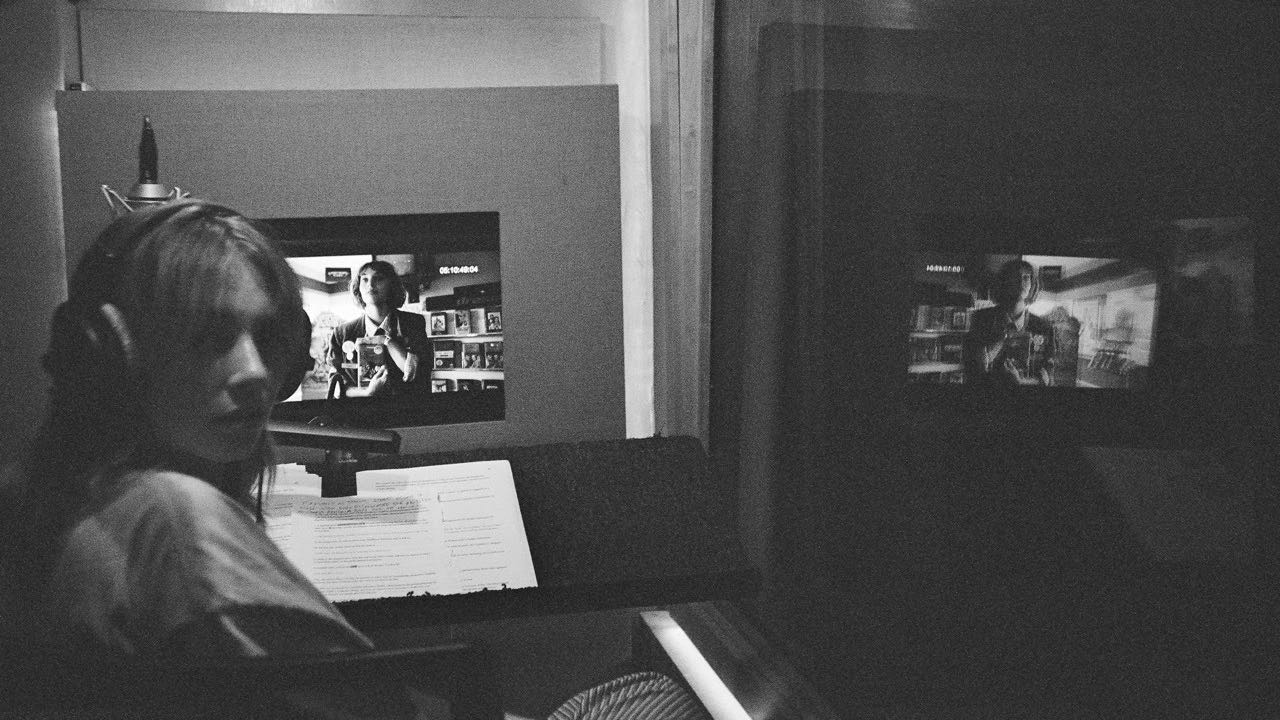

Perry’s film, well narrated by Maya Hawke, features dozens upon dozens of meticulously researched clips from movies, TV, training videos, and commercials set in and around video stores, from seedy exploitative cinema like Toxic Avenger Part III: The Last Temptation of Toxie to blockbusters like Men in Black II. The most famous movies with video stores or video tapes as a theme all get coverage here, including Clerks, Videodrome, and The Ring. Hawke’s own father makes an appearance in a clip from the year 2000’s vision of an ultra-modern Hamlet.

Some of these clips run for far longer than it takes to make the point, drawing the viewer into the plot of the movie and then jerking them back to reality when the clip ends; an unsettling experience. One particular example is the 2008 dramedy Good Dick, cited as the last mainstream film containing present-day scenes in a video store; Perry clearly doesn’t like the movie, but spends a lot of time and plenty of clips on it regardless.

The documentary is overlong and seems to make its point very early on before hammering it home throughout the extended runtime: video stores—both mom-and-pop shops with the beaded curtains that led to the adult sections and corporate, sanitized behemoths like Blockbuster—were in so many movies because they were such a huge part of our culture. Because they were such a huge part of our culture, they made movies seem more grounded and lived-in and relatable. Everyone remembers the episode of Seinfeld with the staff video picks at Champagne Video: it’s the B plot of “The Comeback,” the one with the famous George insult.

Perry explores many aspects of the video store and its placement in cinema, from the guilt and shame revolving around renting adult movies to the ubiquitous and extremely annoying late fees, to the rise of DVDs, to the know-it-all video store clerk. By the end of the documentary, you may have the strong urge to travel back in time, just so you can go to a video store and rent a movie.

We’re in an age where even college students aren’t old enough to remember heading to a Hollywood Video to pay extortionate late fees, trying to rent the latest movie only to come up empty, picking out a disappointing sixth or seventh choice, and forgetting to rewind. This cultural iconography has been erased from existence as much as the horse and buggy, dial-up internet, or the 8-Track. Perry both laments this loss and explains why and how video stores meant so much to us and to filmmakers at large. He could’ve done it in two hours instead of three, is all, and it would have made for a much tighter, more engaging documentary.