Pickathon

July 31–August 2

Pendarvis Farm

Happy Valley, OR

The normally pastoral, rolling hills of wheat that carpet Happy Valley, OR, a small town a half hour outside of Portland, are usually dry by August, but in one of the hottest summers on record, the terrain has become drought blighted. I showed up at the rustic homestead of Pendarvis Farm on Thursday, just after noon, to set up my tent for the weekend. This is when the grounds of the annual Pickathon music festival are open to the public. Despite the fact that the festival wouldn’t start for another day, the forest beyond the stages was already relatively full of pitched tents and well-stocked campsites. Volunteers, crew, and artists had certain areas locked down a week in advance. At this point, it was well on its way to looking like a hipster refugee camp in the woods.

Setting up camp at Pickathon is no walk in the park. It’s a harrowing slog that in 100-degree weather feels like an Iron Man competition. Lugging my tent and a few provisions the quarter mile from my car to the site left me drenched and questioning whether I might be having a stroke, or at least a minor heart attack. I left after pitching my tent wondering if this was worth it, or even worse, if I’d gotten too old for such follies. Camping—so much effort for so little comfort.

But with Thursday’s grueling work behind me, I was free to enjoy myself on Friday. The prior day’s painful ordeal quickly gave way to pleasure as the sun went down and a soft breeze set me sailing toward a series of sublime performances.

Proximity may not seem like the most essential element of a musical experience, but the relationship between artist and audience is symbiotic. And the closer they are to one another, the more mutually influential.

This is one of the reasons that performances at Pickathon so regularly tap into whatever vessel it is through which artist and audience ride, pulsing energy back and forth in both directions. It’s a form of intoxication, one of the best.

Perhaps no artist tapped into the throbbing vein of ecstasy and infused it with more energy than Kamasi Washington and his band, who, on Friday night in the Galaxy Barn—a wooden shed that one might expect to find at Neil Young’s house—invoked spirits from time immemorial, taking the music beyond performance and well into the realm of spiritual ceremony. Washington (along with Thundercat, who also performed at the festival) represents the shape of jazz to come. But what was so startling about his band’s show was how relative time seemed in their grasp. Led by Washington’s otherworldly tenor sax, which summons Coltrane, Shorter, Ammons, and Rollins, the group intertwined elements that seemed at once primordial, tribal, modern and futuristic.

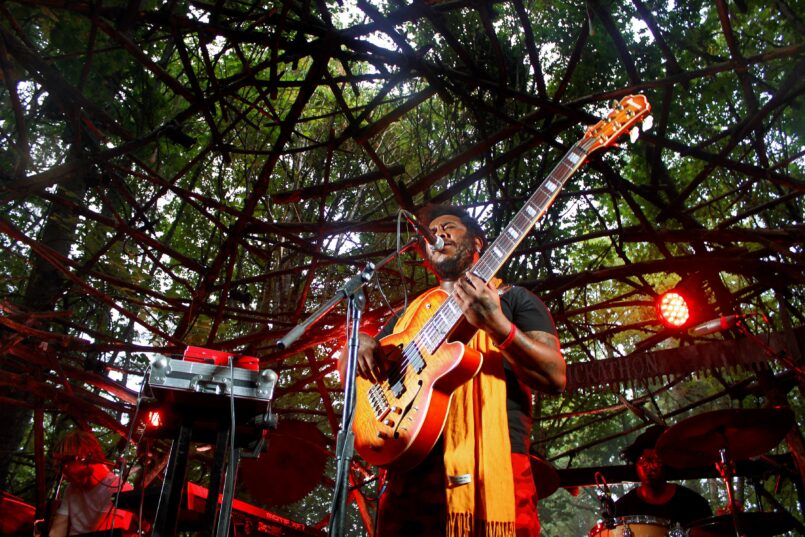

On the Woods Stage, down a winding forest path that opened into a tree-shrouded clearing filled with hay bales and a stage covered by a canopy of branches, the bass virtuoso Thundercat led a power trio (bass, drums, and keyboards) even further into the modern fusion realm. This band would fit in perfectly among mid-seventies jazz-rock bands like Return to Forever, Weather Report and The Mahavishnu Orchestra. Thundercat, his head leaning back, with his face smiling beatifically upwards, thoroughly shredded his bass, not so much in a display of chops but in absolute delight, while his drummer nearly played holes in his kit.

When most people think of music festivals, long lines, exploitative pricing, trash, and general discomfort come to mind. All are kept to a minimum at Pickathon. Lines for food and beer are generally in the single digits. The prices are comparable to any local bar, and the food and drink comes from some of the city’s better food carts and restaurants. Reusable dishes and cups reduce waste and there is a refreshing lack of corporate presence. Festival organizers put a cap on attendance and avoid obvious headliners that draw too broad an audience. This might seem counterintuitive, but if too many people are crowding around one stage to see someone special, it takes away from the magic—better to have a larger number of interesting fringe artists scattered throughout the grounds, dispersing the already-cozy crowds.

Since all of the artists perform at least two sets, they’re around for a couple of days enjoying the festival as fans. This further erodes the barriers between performer and audience. It’s common to watch someone perform and then see them passing through the crowd or sitting next to you at another show. No one’s a huge star, so there’s nothing more than casual conversations or appreciations exchanged. There are no mob scenes.

The proximity of the audience to the artists during performances is equally close. Making eye contact with the performers is the norm, especially at the Woods Stage, which feels more like a campsite than a venue. In these settings, the artists know exactly who their audience is and how they are responding. There’s no hiding behind stagecraft or artifice. It’s the music and its delivery that counts and carries the moment.

No matter how packed with peak experiences an event may be, at the end of three days of nearly 100-degree heat, caked in inches of dust, and subject to constant sensory overload, fatigue sets in. What felt a bit like summer camp the day before becomes oppressive. Covered in sweat, slightly beer drunk (is a lighter craft beer such a crime?!), it’s not hard to imagine one may be here forever, and may always have been. An exit sounds almost more exciting than another show, while a shower, modern plumbing, and an actual bed seem almost mythological. But this is what second, third, fourth, and fifth winds are for.

And that’s precisely what carried us to Leon Bridges’ Sunday set. Backed by a six-piece band, Bridges was a perfect culmination to the weekend. His breezy, light-footed, gospel-tinged soul provided the appropriate uplifting note to go out on. The Fort Worth, TX, native delivered on the hype, performing most every song from his debut album, Coming Home. The band fed off the love from the crowd, clearly relishing their interaction with each other and the audience, recognizing they were somewhere special—aware and even slightly amazed by the preciousness of a prolonged ecstatic moment.

- Sinkane on the Meadow Stage. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Little Freddie King in the Lucky Barn. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Betsy Wright of Ex Hex on the Mountain Stage.

- Rodrigo Amarante on the Meadow Stage. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Leon Bridges on the Mountain Stage. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Leon Bridges backing singer Brittni Jessie on the Mountain Stage. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Leon Bridges on the Mountain Stage. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Howe Gelb of Giant Sand in the Galaxy Barn. Photo by Casey Carpenter.

- Erika Wennerstrom of Heartless Bastards at the Woods Stage. Photo by Casey Carpenter.