Between their recently extended 50th anniversary tour and filmmaker Chris Smith’s new documentary named after its subjects, there’s a strange sensation that washes over any true fan of Devo—the Akron-reared experimental post-everything ensemble co-founded by Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale: nostalgia. Their snark-but-serious claims that man would devolve beyond ape-dom; their iconic brand of test-pattern electro-punk, which morphed into smoother, noodling new wave; their lyrical sensibilities pitched toward angrily anti-corporate socio-consciousness—Devo was never an act which contained sentimentality.

There is no Devo love ballad, or even any softer song in their catalog on which to hang the hat of mawkish emotionalism. There’s only sex, stoicism, low art, and the double-sided coin of conforming and liberation, choke-yelped from beyond the squall of in-the-pocket rhythm and angular fuzzing guitars. And yet, seeing this all at once—from their start at Kent State and Mothersbaugh and Casale’s twin DIY aesthetic to their long, white-noise-filled run with a major label, despite their anti-corporate truth—tugs on your heart strings. Sure, it’s a musical tug different from, say, watching HBO’s recent Billy Joel documentary, but a musical tug nonetheless.

Chris Smith is a large part of how and why the light pours into Devo’s long saga. The director behind films such as American Movie, Jim & Andy, and Fyre, the creator of series such as The Disappearance of Madeleine McCann and 100 Foot Wave, and the producer of Tiger King understands what it means to be a Midwestern oddball due to the fact that he, too, was once a kid in America’s industrial heartland who felt at odds with rigid communality, and who busted out of L-7. Such outlier status as Smith’s allows him an ease of relating to Devo’s co-founders. “I could have been one of them,” he recently told me in an interview about the film for another outlet.

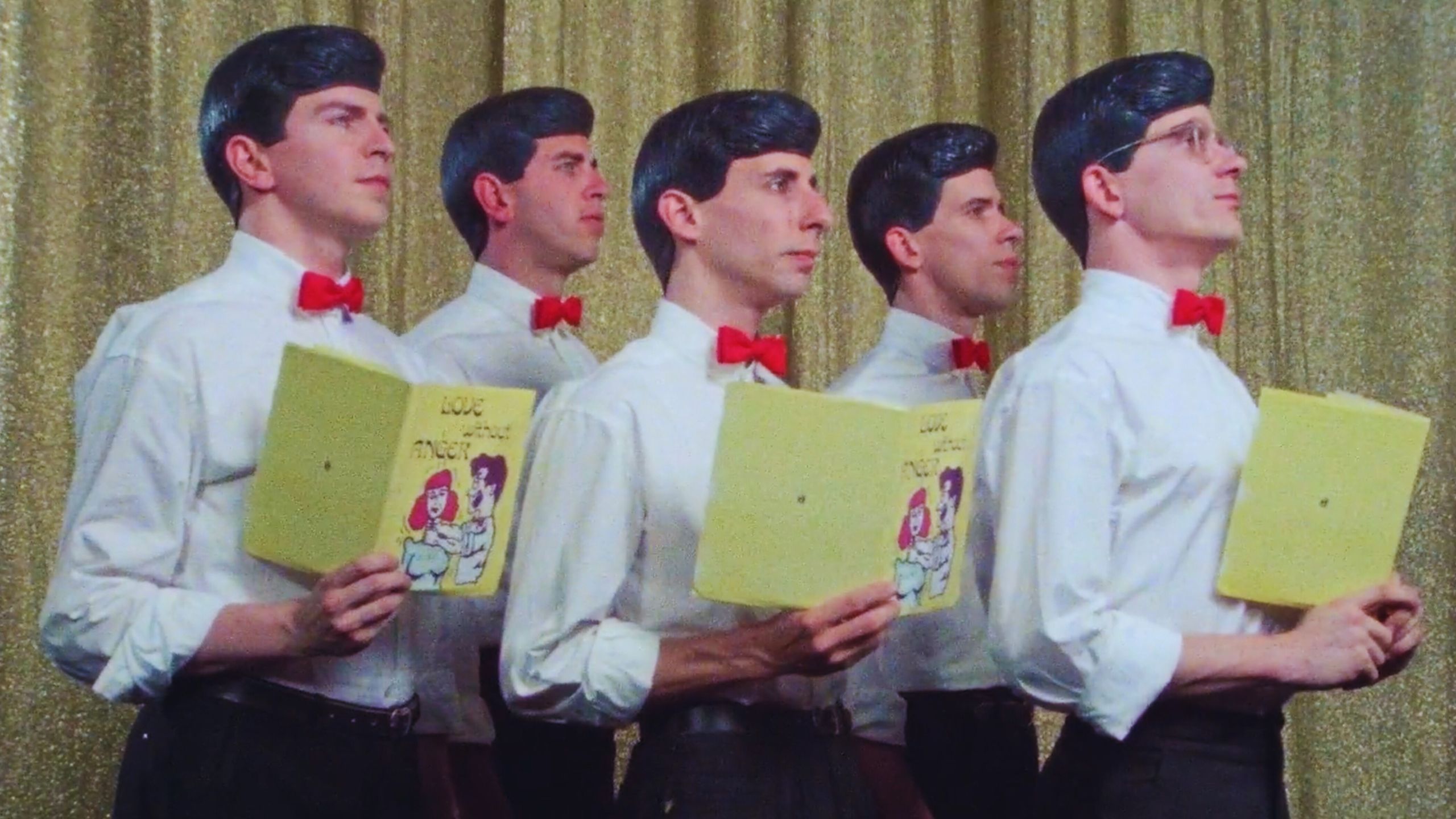

Along with taking his Netflix audience for a rough ride through major touchstones such as Devo’s seminal Saturday Night Live appearance, their mentorship from David Bowie and Brian Eno (even though Devo screwed with Eno’s production mixes), their filmmaking time with Neil Young, and their early ownership of the first-year MTV airwaves (few other bands beyond even had videos), Smith shows off a wealth of the band’s earliest on-stage experiments in performance art and avant-garde electronics via found Super 8 and 16mm rarities. Seeing Devo flail and fail after their early successes with MTV, and their fall from the charts after the mega success of “Whip It,” is documented through old VHS tapes and previously unseen live footage. These vintage film clips with their warped angles and blurry closeups are the true heart of Smith’s documentary—the thing that made Devo bold, beautiful, and important when it came to experimental American music.

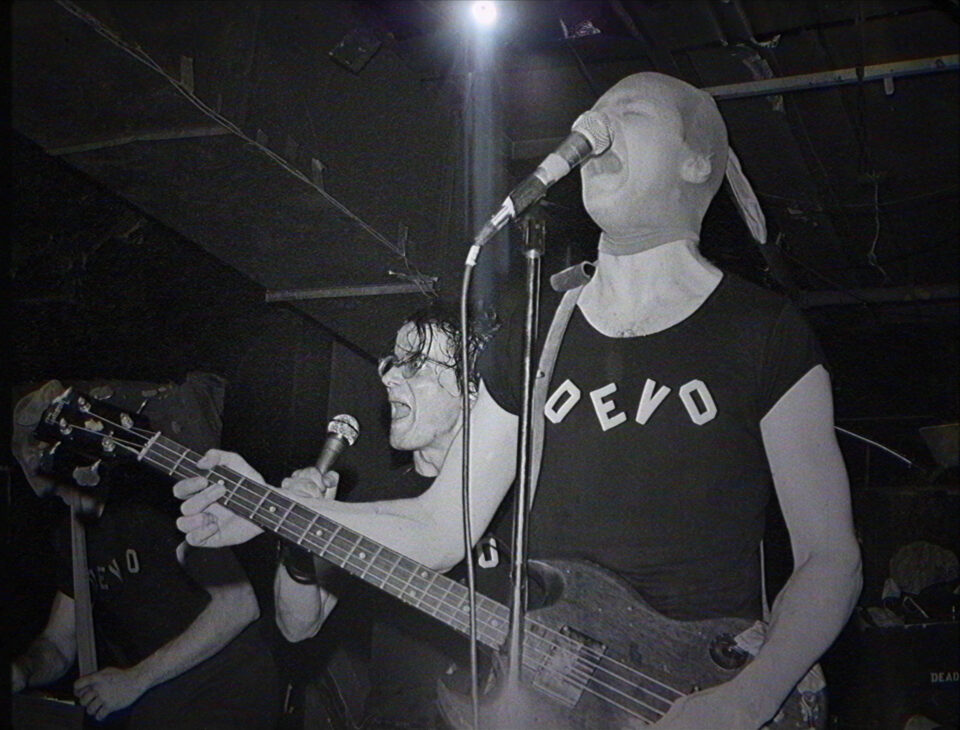

Devo. Jerry Casale and Bob Mothersbaugh performing. Cr: Courtesy of Netflix

The soul, however, of Devo, of Mothersbaugh and Casale, and of Smith’s fresh documentary is their recollection of the Kent State student massacre—a pivotal moment in the American teen protest movement that sadly goes overlooked in the present day. The younger, burgeoning abstract-art aesthete with his poor eyesight but dynamic DIY vision (Mothersbaugh) and the slightly older radical with his socio-political sites set beyond Darwinism (Casale) were students at the university in 1970 when a slaughter of the lambs took place at the hands of the National Guard over the right to protest. Such political brutality, blunt dictatorship, and overawing government intervention (sound familiar?) is what made Devo build its anti-everything machinery, and gives Smith’ documentary an irresistible urge—I mean edge.

Devo. Jerry Casale and Booji Boy on the set of the Satisfaction music video. Cr: Courtesy of Netflix