Marty Mauser is unrelenting in his pursuit of greatness—or at least his idea of it. At 23 years old, he’s one of the best ping-pong players in the world, dead-broke, launching a charm offensive on every person he meets. He’s as skilled as anyone on the table, unafraid of using and then breaking those around him, all for a dream that he’s singularly decided is both world-shattering yet obtainable. Marty is grittiness pretending to be opulence. And for all 150 minutes of Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme, the boy-wonder doesn’t stop running.

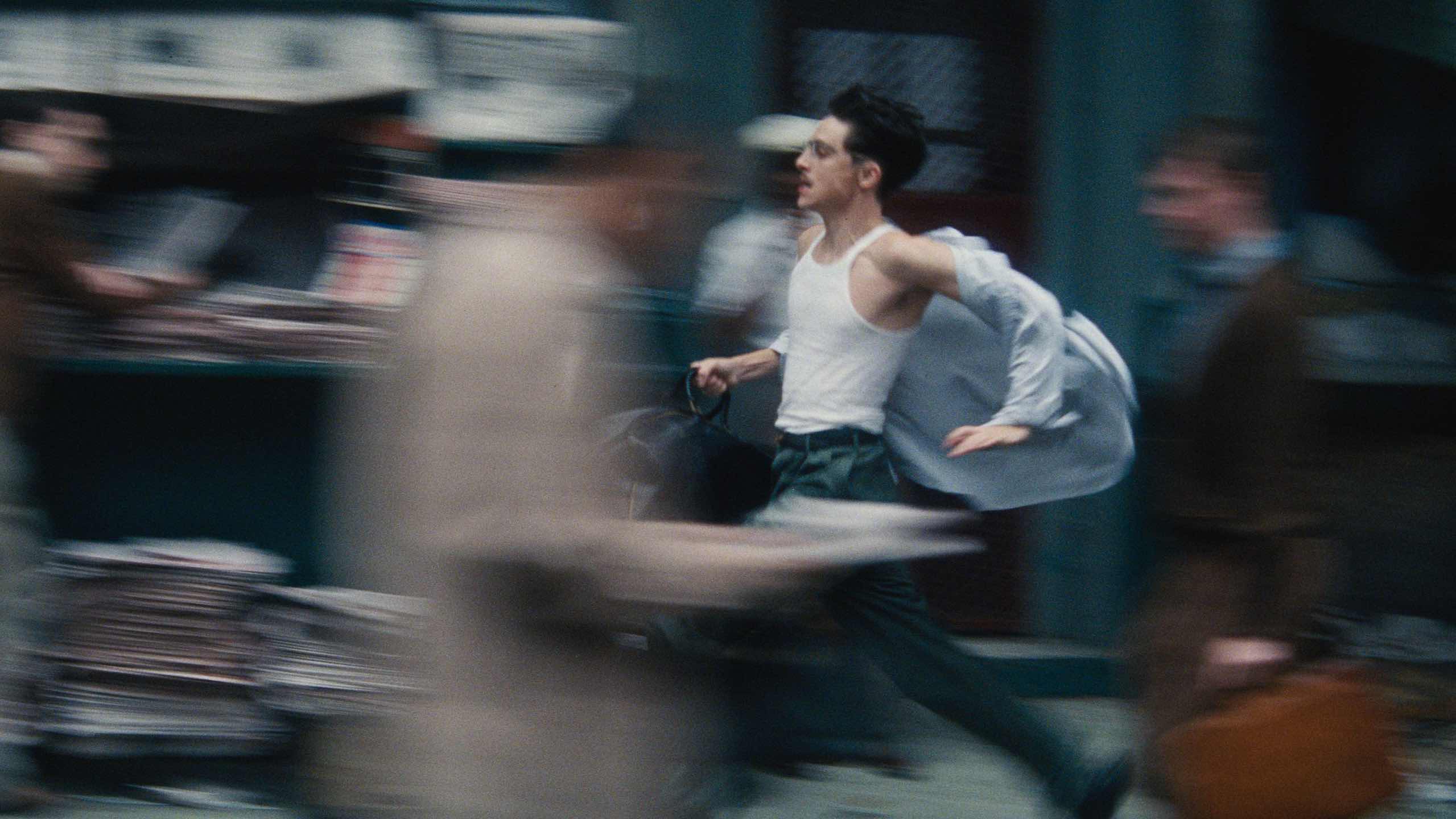

Safdie’s film moves at a breakneck speed, with Mauser first sprinting around New York City, then around the globe, to show that he’s the world’s best table tennis player. It’s all about proving to others that he’s the best: not necessarily being crowned in a quiet room, but lauded on a big stage. He’s equally despicable and charming, speaking at a mile a minute, weaseling his way in and out of hotel rooms with movie stars or shady businessmen. Timothée Chalamet puts the entirety of his body and affect into Marty in a generational performance. His own pursuit of acting greatness can’t be shoved aside, either, as the actor and character meld in their shared belief and talent. He’s cutthroat, grifting and training in succession, repeating this cycle until violence comes and then stays. His commitment is plain to see, on display in the extensive ping-pong scenes and the sweat ruining every white shirt he wears. This is Chalamet’s film from start to finish, a full-on star vehicle that he didn’t need but so clearly wanted, possessed with a verve and electricity that infiltrates the audience's collective pulse and heart rate.

Safdie’s script, which he co-wrote with longtime producer and collaborator Ronald Bronstein, follows Marty through several months in the 1950s, from the British Open to the Harlem Globetrotters, from shabby NYC apartments to the World Championships in Japan. Marty meets retired actress Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow) and her magnate husband, Milton Rockwell (Shark Tank’s Kevin O’Leary), becoming infatuated with the former and indebted to the latter. And he’s often smooth enough to pull both relationships off, greasing the wheels every so often until they inevitably fall off. Paltrow is pure magnetism as Stone, who’s interested in Marty’s excitement despite his immaturity. O’Leary is a clever bit of casting by Safdie—playing a wealthy man doesn’t seem too different from the rich investor’s own persona. Filmmaker Abel Ferrara and Tyler Okonma (a.k.a. Tyler, the Creator) even show up in isolated scenes that keep the narrative on full tilt.

Yet it’s Odessa A’zion who brings the best out of Chalamet. As Marty’s childhood friend and lover, Rachel, she allows Marty to be at his worst. She’s in an abusive marriage and working at a local pet store, abetting Marty’s addiction to perceived success. She wants him to be happy more than any other character in the film, even though she likely also stands to gain from that happiness. A’zion becomes a focal emotional point of the film, and her broken, angry, joyful face lends credence to the fact that Marty’s choices have consequences. The synthy score by Oneohtrix Point Never’s Daniel Lopatin beats its way as pure adrenaline, mirroring the speed and intensity of Marty’s matches and the way he lives his life: on the razor’s edge. It’s thumping in scenes of basement training sessions, exhibition matches, and shabby rooms. There’s no nightclub or wild party—only the next match and the money needed to get to it. The score, like the film, won’t relent.

Marty Supreme remains about individual achievement, about the American idea that the country and its people are a cut above the rest of the world. Marty feels an innate responsibility to show that an American can be the best ping-pong player in the world. On the periphery of the film are the aftereffects of World War II, frayed Japanese-American tensions and the political goings-on of a country rife with patriotic pride. But the man at the center displays the hubris of this American individualism and exceptionalism. Safdie’s film can play like a sports movie, if that’s what the viewer wants, writing just enough likability to keep the audience rooting for Marty. Most of that credit belongs to Chalamet, who somehow maintains charm even without his morals or dignity.

It’s a big swing of a movie from Safdie—sprawling, tireless, consequential. But it’s a swing that connects on levels of character, performance, tone, picture, and sheer energy. Marty Supreme is electricity personified, a bolt that will light up the sky only to burn anything and everything it touches. FL