It’s been twenty years since Dan Bejar started Destroyer. Poison Season, his tenth full-length under that name, seems like a perfect culmination of all those years—a complex and eclectic collection of songs that veers between dissonant orchestral arrangements and starkly cinematic soundscapes, all of which provide a setting in which Bejar’s characters spring to life. Ever esoteric and idiosyncratic, the album follows on from 2011’s Kaputt, which, thanks to widespread critical acclaim, saw the Vancouver artist’s profile rise significantly.

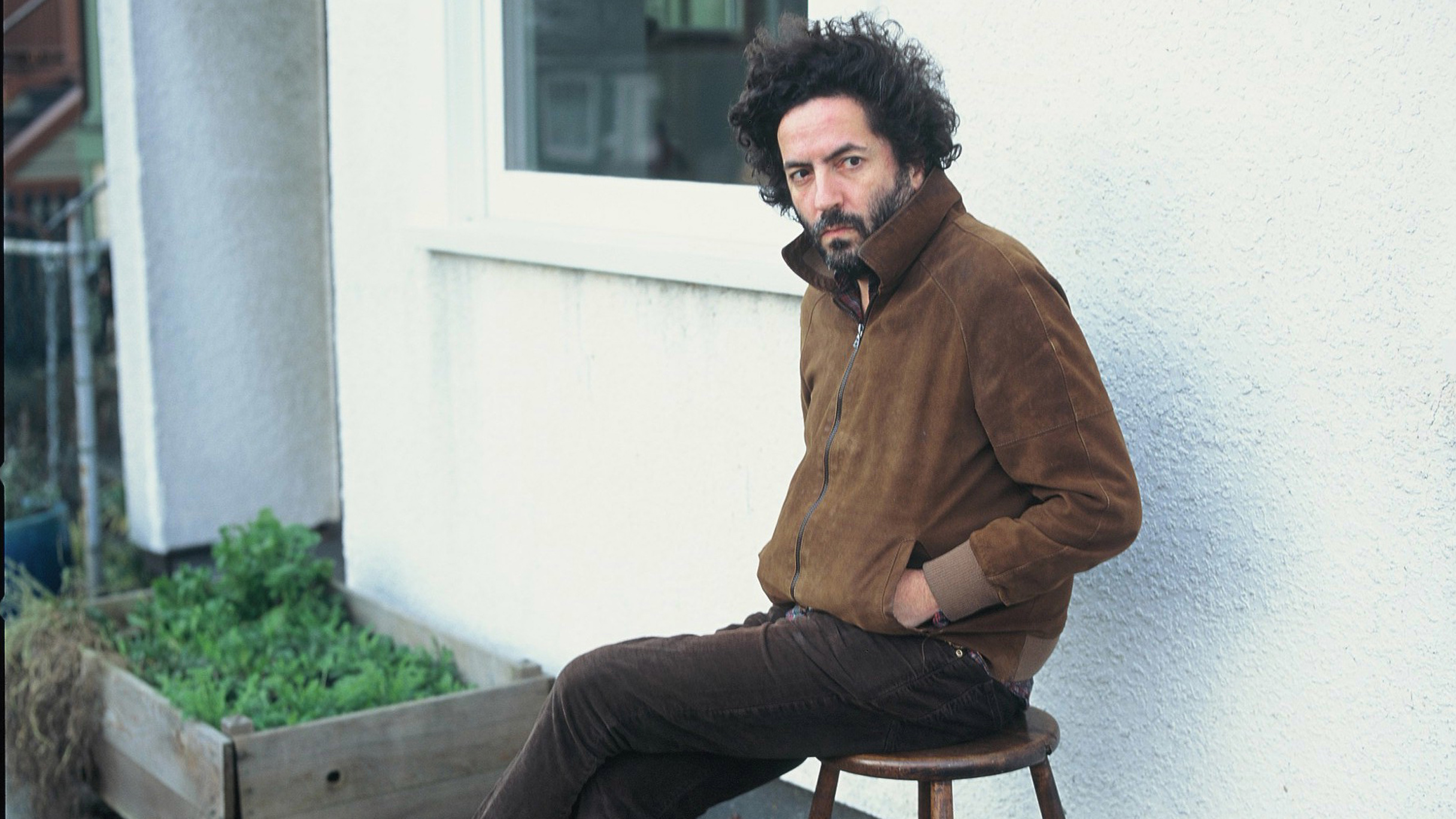

Not that it’s made any difference to Bejar’s approach. Poison Season is an album—much like the nine that preceded it—that exists very much on its own terms. Its baroque, neo-classical-cum-classic-rock compositions span both time and distance as the record explores the most inner (and, for that matter, outer) reaches of Bejar’s musical and narrative imagination. It’s an album that exists as much in the 1970s as it does in 2015—one that’s as mythical as it is rooted in the real word and as unclassifiable and unruly as it is meticulously plotted and mapped out. Not that Bejar would necessarily agree with any of that. Sitting in the relaxing (yet also continually noisy) backyard of a Brooklyn coffee shop, the forty-two-year-old musician is almost dismissive of Poison Season at first, before opening the door to the innermost workings of his mind and creative process.

What does Poison Season mean to you?

I don’t think it has a literal meaning. I think I came up with it quite late, much after the record was recorded.

But I meant the record as a whole, not just its title.

Oh. Well, definitely the record as a whole doesn’t mean anything to me.

Because it’s comprised mostly of characters?

No, I just find the reality—or the meaning generated by the music—has a greater meaning than any kind of literal theme I could come up with. To me, there’s moods that it encompasses. Even though it’s quite lush, it feels more dark and foreboding than most Destroyer records, in my mind. There’s kind of a sense of dread to some of the singing and words. It’s more aggressively percussive in a lot of ways. Some of it reminds me of chase music, or spy music. I think it has cinematic qualities that are more central to the album than any other record I’ve done.

You mentioned darkness, and “Forces From Above” especially seems like a very dark song. Was there something that inspired that specifically, or is it just part of the character’s tale that you’re telling? Where does the line between autobiography and fiction lie with you on this record?

The meaning generated by the music has a greater meaning than any kind of literal theme I could come up with.

They’re all constructions, but, you know, whatever you make exists in the light of that day and whatever mood you might be in. That song I saw as a very specific song. It’s not about big forces—in my mind it’s about crushing large-scale, violent, government forces that actually do damage to human beings on a large scale. There’s talk of camps, and I was just thinking about the word “camp” in a twentieth century sense of, like, the internment camp and concentration camp, but at the same time it’s still the backdrop for a romantic sounding song—even though there’s a world in flames in the background.

I’ve found, since moving to America, that I’ve become very much more politicized. I have a good friend who’s very caught up in exposing the corruption of the government and those forces you just mentioned. How does that kind of stuff affect what you do as a musician? Do you think you have a duty to reveal what you think is going on in the world, and is that what you’re trying to do in this song?

I have to say I’m not really a politicized person, but I think it just creeps in because I think about the world—the Western world, at least. And even in the four-and-a-half years between records, things seem more overtly politicized. Which is kind of weird because I’ve never really experienced that in my lifetime—issues of race and class are now starting to be seriously discussed in very open, mainstream kinds of ways. The way that the world is fed and does business is kind of being critiqued. But I don’t know how that fits in with the Destroyer world, where, unfortunately, things have to exist a bit more as an adventure. But it looms. And I think it’s always been in Destroyer songs—there’s always been a dissatisfaction with the world at large, a kind of feeling of being crushed by the world. Sometimes it’s just more explicit than others.

In another interview about this record, you said you felt you had to apologize for how poppy it sounds. Do you set out to make things more difficult? Obviously, you can write a great pop song, but if it’s your natural tendency to write catchy hooks, do you feel the need to mess it up?

Yes. That’s funny. No one has ever asked me that question, but I would say every single record I’ve ever made I’ve intended to sound more severe and gnarled and dissonant and upset than they’ve ever turned out. And that’s something that’s a conflict inside of me. Part of me wants to be true to what I see as an abrasive or distorted core at the heart of my lyrics or my singing with a music that’s equally messed up, but then the other part of me is quite conservative and traditional and in love with song structure and songwriting tradition, and maybe not American pop music, but definitely the music that would have been on the radio in the UK over the last fifty years. It holds sway over me. And I think once you start doing something, it’s important not to crush it with your concept—you just need to steer into it. You know what feels good and you know what feels forced. And I think I’ve gotten better at it over the last couple of albums.

That’s always been in Destroyer songs—there’s always been a dissatisfaction with the world at large, a kind of feeling of being crushed by the world.

Obviously, Kaputt put you on the radar much more than you had been before. Is this in some respect a reaction to that success?

No. I don’t think it was so successful as to warrant me reacting against it! I’m hardly walking around with a sweater over my head not wanting to be recognized. But it did make some very tangible changes in my life. For the first time ever, Europe started caring about Destroyer and we started going over there a bit. We actually started to sell some records over there. It gave me a recording budget, which was probably three times more than the previous one, and I blew it all on this record. I just hope you can hear it! There are a lot of people involved in this record, and that’s something that definitely couldn’t have happened pre-Kaputt. A lot of these ideas are ideas I’ve maybe had for a while, but just had them in the back of my head because I knew to execute them the way I wanted was impossible.

With that in mind—and I know this record is barely finished—do you have any sense of where you want to go next?

I don’t really know. It’s the early days. There’s a certain style of song on this record that feels maybe like a path I could explore more. I would say that’s more the crooning numbers, which are kind of quieter—you know, embellished and ornate in their own way, with subdued horn arrangements. It was a bed of music that I enjoyed singing to, and it felt quite natural. I could see exploring that world a bit more. But I also think it could just be fun for me to hunker down and make a fucked-up solo record with a drum machine or something, There’s a Riot Goin’ On-style. But more than anything, I’m just trying to get my head around how to play these songs on a stage. Because that’s something that’s looming. We’re not going to have that much time to figure it out and it seems like a bit of a riddle. So I’m kind of excited by that, but I do live in a bit of fear as well. FL