Rebecca has lost her son. Last night she drank more wine than she’s used to, and she has slept through the better part of the morning. When she awakes, Tomas is gone. Deaf, damaged by Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, on the cusp of teenage angst and awkwardness, he has left the home in his new wetsuit. Rebecca goes to comb the beach, desperate for some sign of Tomas among the living. She fears the worst.

By some strange and wonderful providence, Tomas’ disappearance comes just days after Rebecca, a book translator, received a new manuscript from Tel Aviv. The book concerns a middle-aged couple who have lost their own two children. It contains a word—sh’khol—for which Rebecca can find no easy translation. “There were words, of course, for widow, widower, and orphan, but no noun, no adjective, for a parent who had lost a child.” She wavers in her translation, considering “torn open” and “ripped apart” before settling on “bereaved.” Later, she reconsiders: “shadowed.”

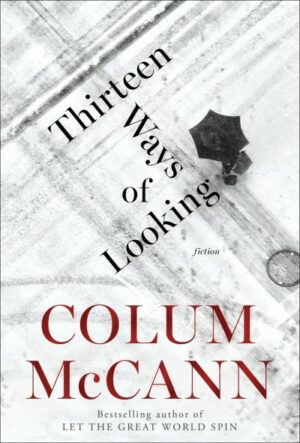

Rebecca and Tomas are the central characters in “Sh’Khol,” one of four stories that make up Colum McCann’s rousing and beautiful Thirteen Ways of Looking. McCann’s previous novels include Let the Great World Spin, a series of tales that intersect at the Twin Towers and orbit through the strange gravity of 9/11; and Transatlanticism, a series of comings and goings across the Atlantic Ocean that span centuries and encompass epiphanies both personal and political.

His gift is in weaving narratives that are epic in their scope but retain their intimacy—miniature dramas told against grand backdrops. Thirteen Ways of Looking includes a novella and three short stories and feels smaller than either of McCann’s previous masterpieces: though one story invokes the Afghan War and another makes non-specific references to tumult in Latin America, these stories are decisively about individual lives, personal fractures, and the power of art to bring balance—if not exactly healing.

His gift is in weaving narratives that are epic in their scope but retain their intimacy—miniature dramas told against grand backdrops. Thirteen Ways of Looking includes a novella and three short stories and feels smaller than either of McCann’s previous masterpieces: though one story invokes the Afghan War and another makes non-specific references to tumult in Latin America, these stories are decisively about individual lives, personal fractures, and the power of art to bring balance—if not exactly healing.

Words and stories, we see, do not take Rebecca’s grief from her, nor do they necessarily make it easier to bear. There is nothing so platitudinous here. But they do help her give a name to her particular fracture, to more precisely identify each scar and fissure along her heart. They help her place her brokenness within a broader, shared mystery—the sweetness and awfulness of having a son, loving a son, knowing how much she couldn’t bear to lose him.

In the midst of writing these stories, McCann himself was brutally assaulted; he saw a woman on the street being assailed, intervened, and evidently got roughed up pretty good. Some of the events in these stories were written before this violent incident, and eerily presage it; others McCann concocted afterward, trying to make sense of what had happened to him.

Regardless of the chronology, all four tales here convey creeping unease, the haunting insinuation of a violence that sometimes goes unnamed. The titular novella leads the collection and is itself modeled on a structure McCann borrowed from Wallace Stevens. He paints an elderly, retired judge who reflects on his own life, unaware that his death (murder?) is imminent. The circumstances of his death are at first cryptic and unclear, revealed to us piece by piece over the novella’s thirteen episodes—some of them diaristic reflections by the judge himself, others told from the perspective of detectives working his case.

And so we see an eruption of violence from various vantage points—the judge looking forward to it, however unknowingly, and the detectives tasked with determining what happened trying to piece it together in hindsight—in much the same way that this collection both anticipates and appraises the violent eruption in McCann’s own life. The detectives are cast as CSI-styled analysts, but also, tellingly, as poets, a metaphor the piece returns to time and time again.

These stories are decisively about individual lives, personal fractures, and the power of art to bring balance—if not exactly healing.

“Poets, like detectives, know the truth is laborious,” one episode begins. “It doesn’t occur by accident, rather it is chiseled and worked into being, the product of time and distance and graft. The poet must be open to the possibility that she has to go a long way before a word rises, or a sentence holds, or a rhythm opens, and even then nothing is assured, not even the words that have staked their original claim or meaning.”

McCann’s characters all seem to have the puzzle pieces of reality laid out before them, but the full truth seems somehow elusive. In a story called “What Time is It Now, Where You Are?” McCann blurs the line between poet and detective further, giving us a writer who’s stuck on a story about a soldier in the Afghan War. The story is a straight-ahead but compelling walk through the writer’s process—a sort of fumbling through shadows for an austere truth that’s only faintly visible. Fiction itself is a case the artist must solve, and it inflicts its own ghostly bumps and bruises.

It’s worth noting, perhaps, that this story replicates the thirteen-episode structure of the novella, albeit in a greatly condensed format, and for that matter that the myriad security cameras that haunt the novella reappear in the final short story, “Treaty,” suggesting infinite angles on the same grisly scene—multiple perspectives for the poet, myriad clues for the detective.

“In the hands of detectives,” McCann writes, “the past never stops happening.” His characters in this fine collection are caught between repeating pasts and uneasy futures, personal chronologies arranged around violence and grief. There is never any guarantee that they’ll piece things together in a way that makes sense—but perhaps there is something redemptive just in the attempt. FL