Los Angeles is not a bad place to go see a movie. Whether you’re looking for some cult vibes, some art-house shit, or the Cineplex experience, it’s out there, and it’s often surprisingly proximate. But the audience for movies about books about movies directed by critics and starring directors is not robust. And so, in order to see Kent Jones’s new documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut, I had to make a pilgrimage. I had to go to the other side of town.

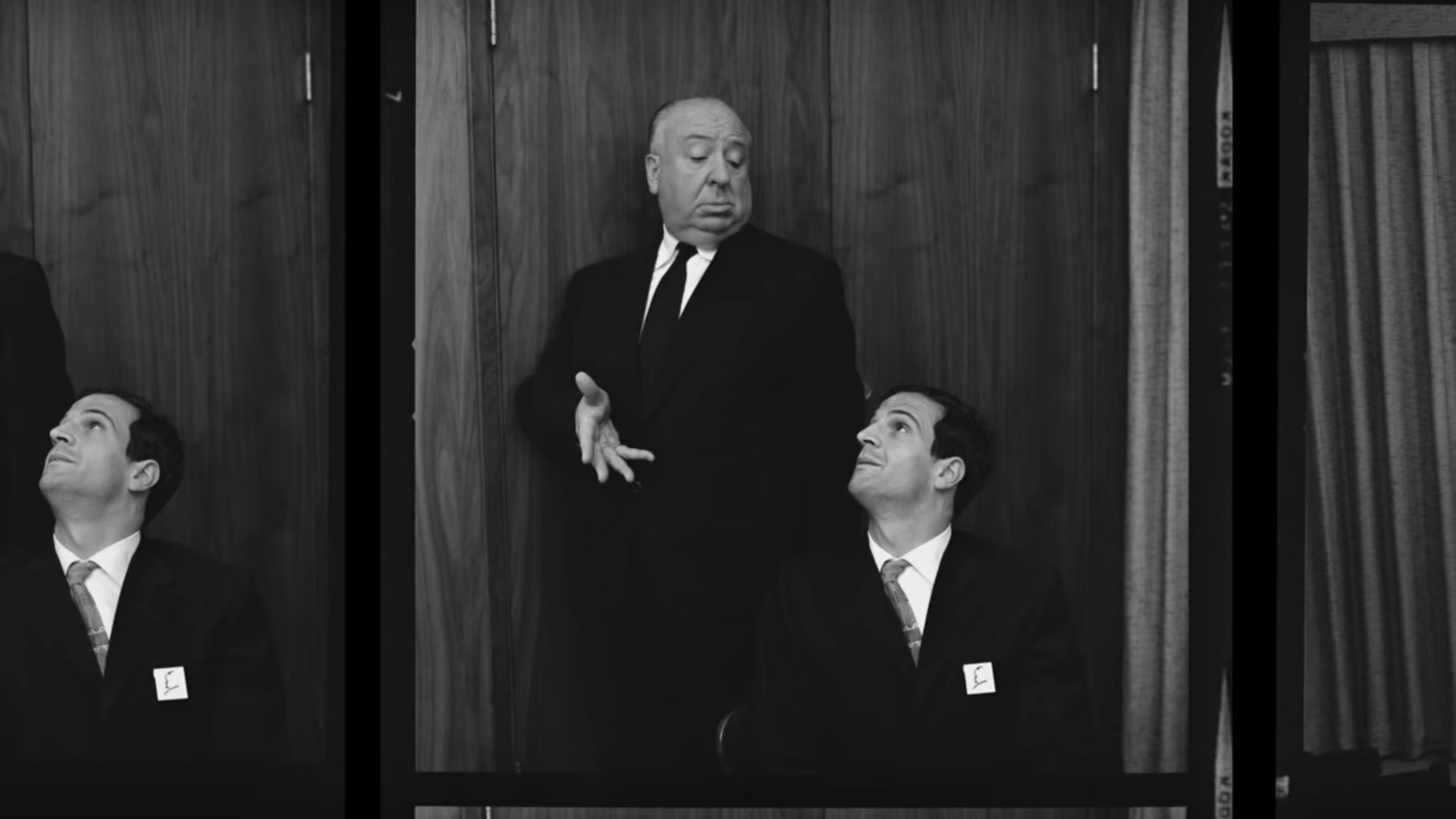

In karmic recompense for this effort, I wound up at a very suitable kind of relic: a single-screen theater situated next to a real-life video rental store. The ideal place to see a movie about Alfred Hitchcock, then, as in his time he was also both a relic of the past and a beacon to the future. Jones takes that tension seriously in his film. He wants to find out what makes Hitchcock—a kind of geometrician of emotion, as he is presented here—work: not just in the ’40s, when he first hit his stride, or the ’60s, when Francois Truffaut hit his, but now.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JuhPG-YA40

And although that fundamental question is never going to be answered completely, this new documentary certainly covers a lot of the working parts, and without giving short shrift to contextual work, either. In addition to the basic questions of what makes a movie good, we also learn about how the source material for Jones’s documentary (Truffaut’s 1966 book of interviews by the same name) came to be, why it mattered at the time, and how its lessons still influence filmmakers today. The book itself actually receives very little in the way of explanation here—surprising until you consider that in a runtime of eighty minutes there’s not a lot of time for anything. Nevertheless, the movie offers a lot that the book could not, including stills, press clippings, movie clips, contemporary photos, audio excerpts, and talking-head reflections from a remarkable set of heads, including directors Martin Scorsese, Peter Bogdanovich, and David Fincher.

Aside from the stunning array of clips (many of which will be familiar to nearly all, but some of which certainly came as a surprise to me), the main feature of the film is the interview content. Truffaut’s original interviews covered every single film Hitchcock had done up to that point, and it is through the discussion of these films that the two directors wind up discussing light, sound, art direction, acting, surprise vs. suspense, entertainment vs. art, and what it is that makes a movie work. This documentary can’t possibly delve as deeply into the individual films as the book did, but it is similarly incisive—and it offers new insights even when tackling old topics. In a segment that touches briefly on the importance of editing, David Fincher (a clear—and very charming—disciple) presents, without attribution, a theory of film that is nearly identical to Hitchcock’s, with both men saying, each in their own style, that film is mainly concerned with speeding slow things up and slowing fast things down.

We see Hitchcock’s influence in movies that hold our attention without appearing to try, in shots that make us wonder who we are, in scenes that go too fast, and in scenes where time stands still.

Jones presents the two observations alongside one another so that the debt is clear, and in the end it doesn’t really matter whether Fincher was aware of the source of his insight or not; what’s important is the extent to which the teachings of the master have been internalized by the next generation of filmmakers—the next next generation, in fact. Truffaut relied heavily on that internalized knowledge in order to ensure that, however loose his films might have felt, they always kept the viewer engaged and entertained. The directors here are working in a different age and with a different audience in mind. Few of them would get very far by referring to their A-list actors as “cattle,” as Hitchcock did. But they all speak of Hitchcock with a reverence that, like Truffaut’s, is different from mere nostalgia. They revere him because he still holds a power over them, as he does over us.

Truffaut and his cohort at the Cahiers du Cinema set the terms of the debate in the ’50s and ’60s. They forced us to question the divide between high art and low, demanded that directors be treated as authors, and used philosophical language to describe what they saw on screen. But they also absolutely loved the movies. Jones has the critical chops, of course, but here he eschews some of the old, tired language, and finds his way back to what really concerned the French critics of the ’60s: the question of how these factory-produced cash crops could be so mind-meltingly fun.

There are a lot of reasons for that, of course, and a lot of ways that fun happens. The diversity of the directors that Jones has enlisted (diverse in terms of style, that is) demonstrates the truly fundamental nature of Hitchcock’s impact. He is, in fact, so fundamental that he’s almost impossible to see. (“Hitchcockian” films are rarely that.) Instead, we see his influence in movies that hold our attention without appearing to try, in shots that make us wonder who we are, in scenes that go too fast, and in scenes where time stands still.

Truffaut’s first film, The 400 Blows, ends with a very famous freeze-frame shot. Freeze-frames were not really Hitchcock’s thing, but you can see the connection when expressed in terms of time manipulation. Jones’ film ends on a frozen frame as well, but it features a classic Hitchcock image instead. There’s a metaphorical object in that shot, but rather than spoil it, it’s probably better to just use the word that the directors ultimately default to. Better to just call it poetry. FL