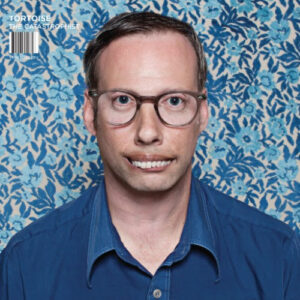

Its members are now scattered as far away as Los Angeles, but twenty-five years after its inception, Tortoise is still a Chicago band—so much so that its seventh studio album, The Catastrophist, started out as a commission from the city. The request was for the band to compose and perform a sort of tribute, combining Chicago’s established jazz and improvisation traditions with Tortoise’s style. It was a fitting assignment for the group that’s been releasing what’s most easily described as post-rock—experimental, nearly entirely instrumental, often improvised.

The first result of the project was five pieces of music, each written by a different member of Tortoise. The second was three performances of that material alongside musicians from the city’s jazz and improv music communities: one in Chicago’s Millennium Park, one at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and one at the Paris Jazz Festival.

The third is The Catastrophist. An album wasn’t part of the initial request, but in the spirit of experimentation, Tortoise wanted to see how far its material could go. The music the quintet wrote for the performances was designed to accommodate solos, spontaneous interpretation, and riffing; they turned those somewhat skeletal pieces into full-on Tortoise songs with the addition of bridges, harmonies, and melodies. The Catastrophist also boasts two (!) songs with vocalists: one a cover of the 1973 David Essex song “Rock On” featuring Todd Rittmann of U.S. Maple and Dead Rider, and one an original track called “Yonder Blue,” which was co-written and sung by Yo La Tengo’s Georgia Hubley.

Ahead of the release of The Catastrophist and with an international tour in support of the album on the horizon, bassist Doug McCombs sat down with FLOOD at Cafe Mustache in Chicago to talk about Tortoise’s influential studio output, all of which has been released by Thrill Jockey.

Tortoise (1994)

Your debut album. First thoughts, recollections?

The main thing about that record was that we still really hadn’t played live very much when we made [it]. We’d probably only had maybe, at the most, three shows that we’d played, and they were all very far apart and they were all very different. I kind of already knew that we were on to something interesting, so when we were able to record these weird ideas that we had and make them into something that was coherent, I really started to believe that we could do just about anything. It wasn’t predicated on any idea that anyone would really like the band or anything, it was more just really satisfying in a creative way.

Millions Now Living Will Never Die (1996)

Millions Now Living Will Never Die (1996)

This is the one where everybody gathered around and paid attention.

The main thing about that record is that we were so encouraged by the first record that we just threw it all out there. We were trying anything and seeing what we could make work. And in a certain way, I think it was kind of like what we did on the first album, but even more adventurous. We were starting to have a lot of confidence in what we were doing, and [we weren’t] afraid to try different stuff [or] to fail. It doesn’t matter if it fails. You don’t have to put it on the record. And John McEntire [Tortoise’s drummer and producer] enabled us to try a lot of experiments in the studio. But on top of that, we were getting better at writing interesting music and getting better at harmony and melody and stuff like that. Just getting better at writing songs.

TNT (1998)

Jeff [Parker] was joining the band. Dave Pajo was still in the band, but Jeff joined also. Dave didn’t really quit Tortoise until that album was almost finished, so there were six of us working on that record. That was the time when everybody had tons of ideas, and we were determined not to let any one of them go unexplored. That’s why it’s a double album, and it’s so long. I think we did end up throwing out a couple things, but we were like, “We have to see each one of these things through to the end.”

And it was just more of continuing to be determined to make this statement. Music can be a lot of different things, and we want to try a lot of different things and still try to retain some kind of our imprint on it—not just make one pastiche and then another pastiche and have them all sound different, but have all these different songs that could have different feels to them and different types of melodic ideas to them and still retain this imprint of what our personalities are in the music.

Do you purposely take the time to let each person have his say, or do you know each other well enough to not have to make such an effort to do that?

Nowadays, the way we work best is whoever has an idea for any particular piece of music that we’re working on is encouraged to try and get that idea onto the song. And if someone doesn’t have an idea, they don’t have to participate in the song if they don’t want to. Or, sometimes it can be more like, “I have an idea for this song, but I’m probably not going to be able to execute it very well. Here’s the idea. Can you try it?” There’s a healthy interplay in the band of idea-swapping and collaboration. It was pretty natural. TNT was recorded mostly in this warehouse that some of us lived in—this warehouse loft space where John had set up his first version of his recording studio. It took us about a year to make that album. It would be like, if you woke up that day and you could hear that John had something playing in the control room, you’d step in and say, “Oh yeah, I have an idea for this song.”

Standards (2001)

Standards (2001)

Standards in a way is probably my favorite Tortoise record, although I haven’t listened to it in a long time. When we started touring around ’95, there weren’t a whole lot of dynamics to our music, and I feel like we were a fairly quiet band. We weren’t exactly not a rock band, but our music in those early days we felt was…not delicate, but there were a lot of “little” sounds. It was more about paying attention to what was happening in the music. And by the end of ’98 or ’99, when we started working on Standards, we had been a touring band for like five years and we had definitely become more dynamic and more powerful as a group. It took Tortoise a while to develop that aspect of our personality. To me, Standards was kind of like that. I know it doesn’t sound like a loud rock band, but it was us being a more powerful band. And I feel like it’s more concise. The things that happen in the songs happen in a more deliberate way, and sometimes even a verse-chorus-bridge kind of way. Occasionally. Not that often.

It’s All Around You (2004)

At that time, we were really putting a lot of focus on the songwriting aspect—getting really detailed about the melody and harmony and how it all fits together. Almost in like a—and I don’t mean this in any kind of egotistical way—almost like in a Beach Boys kind of way. We were trying to get somewhere near that kind of complexity. It was in some way trying to perfect and boil down what we had been doing for the previous ten years. In a way, it’s always kind of like that. We’re in some way trying to perfect the things we’ve done before, or get them to another state.

![]() Beacons of Ancestorship (2009)

Beacons of Ancestorship (2009)

To me, that feels like the first really big gap we had between records. So it was kind of like, now we really have to push ourselves in some other direction. We did a few things, like some of the guys were getting a little tired of the mallet instruments—we always had vibes and marimbas on everything—and some of the guys were like, “If we take that out of the equation, what would we do?” I personally didn’t have any problem with those instruments; I felt like we were creative enough that we could figure out different ways to incorporate them, but what ended up happening was that all the guys got really into synthesizers. To a certain degree, we all were anyway. We wanted to also get more immediate, raw-sounding recordings. It’s All Around You had been this pristine, highly produced thing, so [with] Beacons, there’s a certain rawness to it. The way we work, there’s not always—in fact, there’s never probably ever five people playing a song together in a room, so we tried to get some of that on that record. And it just made a more immediate, sort of rawer-sounding thing.

The Catastrophist (2016)

How do you feel about the album?

I think it’s great. It takes me a while to let it sink in and see how I really feel about it, especially in relation to our other albums. A few weeks ago, we started rehearsing for our upcoming tours—I think we can play every song on the album, which has never happened before with Tortoise. There’s always been like one or two songs that we just can’t figure out a way to play live. But I’m just excited. That’s another thing that happens with Tortoise. When we go out and start to play songs, they start to change. I’m interested to see where some of these songs go. Songs of ours that are twenty years old—it’s subtle and gradual, but they don’t exactly sound like the songs on the record from twenty years ago when we play them live. They’re slightly different, and I’m interested to see what happens with some of the songs on this new record. There are songs on this record that are hard to play, and there are some that are really, really easy to play. And that’s interesting to me, that we have a handful of these pretty simple little songs on this new record.

That’s what I noticed about this one.

Yeah, they’re sort of simple and understated, and I want to see what reactions those kind of songs get. An audience responds to something that’s visceral and dynamic, and I want to see what happens when they get these simpler, understated things.

You talk about challenging yourselves from album to album. Is it something as simple as you all knowing, “This is the album where we didn’t do this, this is the album where we did do this,” or is it more complicated than that?

It’s a little more complicated than that. It can happen on a personal level with some of the stuff, where you’re actually challenging yourself as a musician, but it’s mostly just pushing ourselves to not rest on things that are comfortable to us.

So it can be a hindsight thing rather than, like, “Band meeting, here’s what we’re not doing this time.”

Yeah. I mean, everything happens in hindsight with this band. There’s never any planning. We never have our shit together enough to just plan something and do it. We have to sort of stumble into it and then let it happen. FL