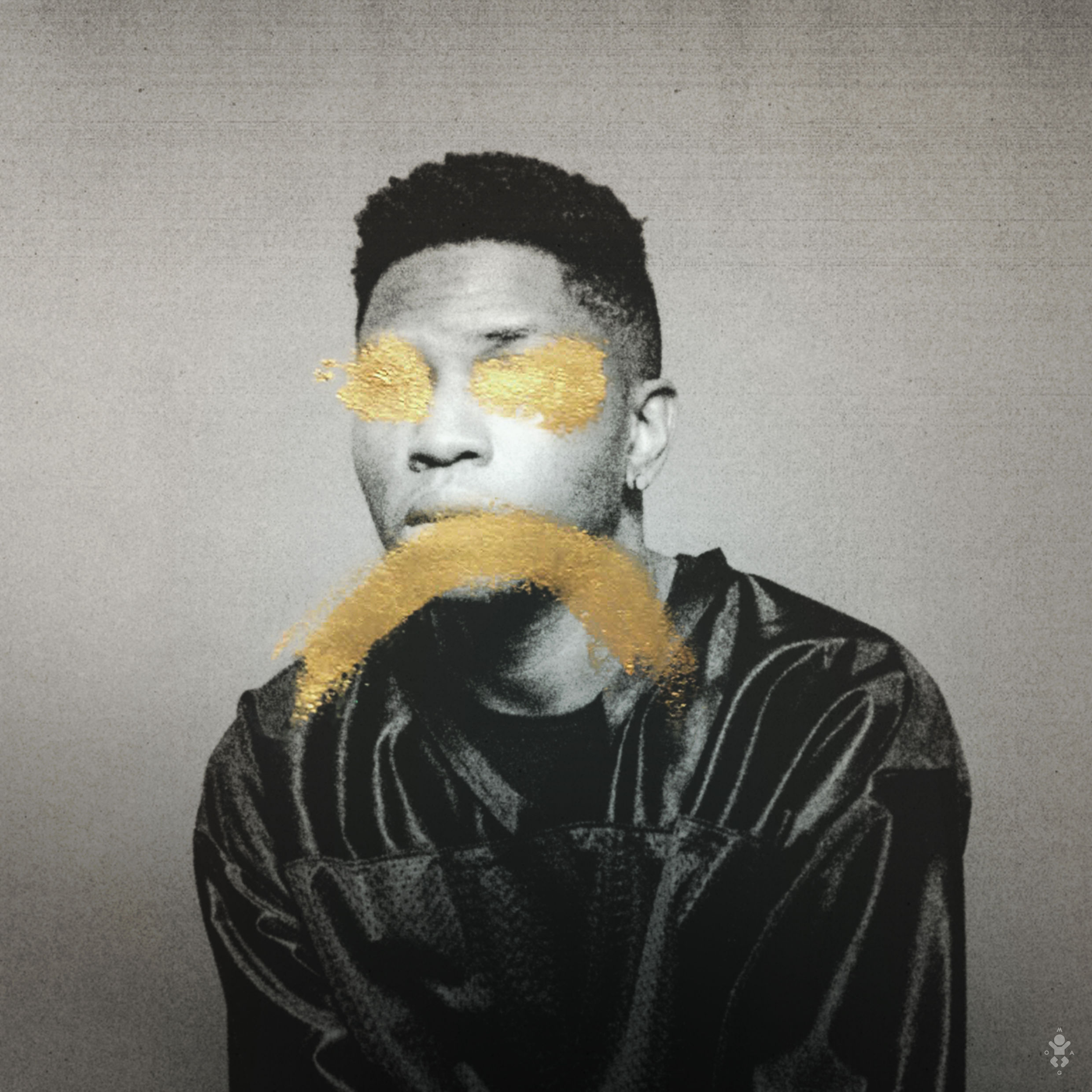

Gallant

Ology

MIND OF A GENIUS

8/10

Christopher Gallant relocated from New York to LA after being told his music was too weird—in order to sell it, he’d have to make it more “this” and less “that.” In response, he self-released an EP, 2014’s Zebra. Gallant’s influences are not more “this” and less “that.” He knows and loves alt-rock alongside R&B. His version of the Foo Fighters’ “Learn to Fly” is enough to make the original’s famously goofy video cover its face in shame.

Ology, twenty-four-year-old Gallant’s debut LP, makes the wait for Frank Ocean’s new album much easier to take. “First”/“Talking to Myself” is one of the best album openers in recent memory. “Weight in Gold,” a 2015 single, caught the attention of Sufjan Stevens and Seal for a reason. If you know anything about him, it’s that vocally, Gallant is virtually untouchable.

The record has the intimate feel of a D’Angelo album, but the sex and romance are largely gone. Love comes up, as it tends to, but Ology is ultimately Gallant trying to find himself rather than someone else. On “Bone + Tissue,” he sings about “spending all your days making days feel shorter.” “Tell me I’m a monument to more than bone and tissue,” he implores.

As promised, there’s no genre to fit this neatly into. “Oh, Universe” is a jazzy interlude. “Skipping Stones” finds Gallant trading vocal runs with the equally smooth Jhené Aiko. “Chandra,” the album’s final full song, is, according to Gallant’s Twitter, “a [D]isney song” about taking too much Tylenol. Indeed, it’s soaring, orchestral, and cinematic, with French horns that don’t seem out of place at all.

Ology is for anyone who’s put at least a couple of decades in, and the titular suffix speaks to that universal relatability. Gallant has carefully studied everything the world’s thrown at him in his brief number of years. Children of the ’90s, with The Lion King and There Is Nothing Left to Lose in their blood, are now in their mid-twenties and putting out work like this. It’s not sarcastic. The energy and heart permeating it is contagious.

In a stroke of genius, the album concludes abruptly—like so many important moments do—with the sound of a vibrating phone. Because nothing gold can stay, and this is certainly gold.