It was 1996, and Comedy Central President Doug Herzog was in a quandary. Politically Incorrect was about to jump ship for ABC, leaving the fledgling comedy network without a late-night talk show—a vacuum Herzog very much wanted to fill.

He had a vision: a daily show that could be both funny and topical, and that would stand as the network’s flagship program. But his decision to hire Madeleine Smithberg and Lizz Winstead as co-creators would have consequences for late-night TV, comedy, and politics far beyond what he could have seen at the time.

Smithberg, a former talent coordinator and segment producer for Late Night with David Letterman, had previously collaborated with comedian Winstead on the ill-fated Jon Stewart Show. (In an odd turn of events, Stewart began his stint as the host of The Daily Show the year after Winstead departed in 1998.)

The pair had been swatting around a different idea for a Larry Sanders–style satire that would depict a failing network and incorporate clips from its terrible shows. Herzog said he couldn’t afford that venture but wanted Smithberg to helm the still-untitled daily show.

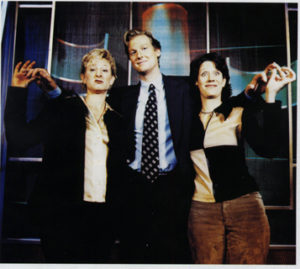

Smithberg, Craig Kilborn, and Winstead on set

Smithberg had recently declined Comedy Central’s proposal that she head the network’s programming but salivated at Herzog’s pitch: she would have an entire year to experiment with the show, and wouldn’t even be obligated to do a pilot.

“That type of opportunity doesn’t exist anymore,” she says.

“We wanted The Daily Show to do something that hadn’t been done before, satirizing the media landscape [and] not just covering the news like [SNL’s] ‘Weekend Update,’” Winstead adds.

Smithberg and Winstead were the captains of the ship, but they needed a steward; ESPN’s Craig Kilborn signed on to fill that role, and the cocky-but-likeable host sat behind the anchor desk for the program’s first 386 episodes. They also tapped the likes of Brian Unger, Stacey Grenrock-Woods, and Frank DeCaro—all of whom had news backgrounds—to serve as early talents on the show.

They were “this accidental family,” as original correspondent Beth Littleford says. And they were one of a kind.

“The Daily Show’s responsibility was to be smart and funny, and our [ethos] was to expose hypocrisy in the media and politics,” Winstead says. “There was so much filler on the news channels, and we wanted to talk about important issues that we could satirize.”

Beth Littleford and Frank DeCaro get hitched

Most of the ensuing twenty years of The Daily Show—especially Stewart’s tenure—have been exhaustively documented. But sorely underrepresented (if not quite lost) in those retrospectives is the headiness of the early years, before young people would claim it as their most trustworthy news source and before sitting presidents would grace it with interviews.

It was a time when Herzog and Unger would battle over the number of sex toy references that could be made in one episode, when DeCaro’s modus operandi was cramming his “Out at the Movies” segments with double-entendres—and when comedic minds finally learned how to successfully mock the news.

“If you ask Doug Herzog, he will say the first year of The Daily Show was the most fun he’s ever had,” Smithberg says. “Because we were stumbling into brilliance.”

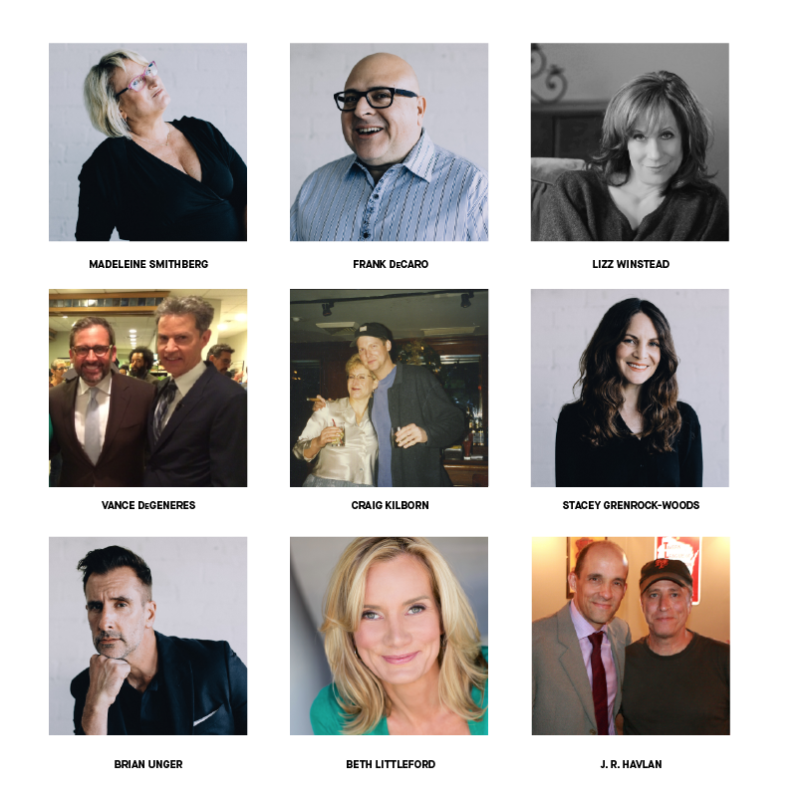

To give that time its proper due, and to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of The Daily Show’s creation, FLOOD convened Smithberg, Winstead, Unger, DeCaro, Grenrock-Woods, Littleford, Vance DeGeneres, and writer J. R. Havlan to provide an oral history of the show’s early years.

Face the Nation

Madeleine Smithberg: It wasn’t really until Brian came from CBS News that we realized what an opportunity we had as a fake news show. There wasn’t enough news to fill all the outlets on television, so the people who were reporting the news made it about themselves, and that was our in. We weren’t making fun of the stories in the news—we were making fun of the way people were reporting those stories.

Brian Unger: The genesis of The Daily Show was rooted in real reporters who came from these respected worlds of writing and reporting, and who brought their rage and anger at the system. I’m not sure the show has the same gravitas now [since it relies more on comedians for its correspondents].

Lizz Winstead: On our first show, [Kilborn] interviewed a woman whose cat was killed by a BB gun, who then channeled the cat through a psychic and wrote a eulogy for her based on what the cat had said from the grave. We knew from that point on that we were never going to stop laughing.

Unger: Frank Rich [of The New York Times] sent me a handwritten note saying, “Thank you for what you’re doing, keep doing it.” And I thought, “What are we doing?” The show really, at its spine, is about journalists abdicating their responsibility as journalists. There are some journalists who are really trying to do their job, but their bosses are just looking for ratings and profit. Now it’s gotten so complex with the digital universe, but we were at a time of great innocence. We were trying to satirize news and the structure and the form of it.

The McLaughlin Group

Frank DeCaro: I was a journalist. I wrote for The New York Times and some other magazines. One of the [other] writers brought me in. It helped that a lot of us came from a journalism background, so we could subvert from the inside.

Stacey Grenrock-Woods: I started as a journalist, did a piece for an MTV pilot, and then The Daily Show tracked me down.

Winstead: I had known Stephen Colbert and saw him on Good Morning America one day and realized they didn’t know what they had on their hands. [Colbert would join The Daily Show in 1997.] And we had Lewis Black [in 1996], whose character fit perfectly into the model of a modern-day Andy Rooney.

J. R. Havlan: I knew Lizz from standup, and she asked me to submit to the show. In my eighteen years there, I looked at the show as having four distinct phases: with Craig, with Jon, after the 2000 election, and when The Colbert Report launched.

Beth Littleford: Some people had dabbled in news, but I was a straight actress doing gender-bending roles and found my way at The Improv via a one-woman show. I was brought in as the pseudo–Barbara Walters. I later did two half-hour “Beth Littleford Interview Special”s on Boy George and Anthony Michael Hall.

Vance DeGeneres: I was not there in the beginning years but was lucky enough to be hired by Madeleine and Jon right before he came aboard [in 1999]. I met Steve [Carell] when he joined The Daily Show [the same year]. I remember seeing his first piece and thinking, “I wish I thought of that idea.” It was really brilliant. We became best friends.

Littleford: We were a little community that pulled together and put on a show with a little-show vibe. There was a feeling in the office of real camaraderie, and we’re all in the trenches together—but nobody got killed.

Grenrock-Woods, Smithberg, DeCaro, and Unger photographed at FLOOD Gallery in Los Angeles by Rozette Rago

The Situation Room

Havlan: There were only five writers at the beginning, and we were busy working on six stories a day. We were trying to write punchlines to a crap-load of stories. Our main thing at the beginning was headline jokes, far more setup and punchline–oriented than in the later shows. The original format was “Headlines,” “Other News” (which was three different stories), “This Just In,” and an interview.

Winstead: Each writer and producer was assigned a major newspaper and a regional area, and we would come in at 8 a.m. and they would pitch stories. We would pick the stories we wanted to do, then talk with the graphics and design departments. We’d meet back at 1:30 for the joke read, Madeleine and I would pick the jokes we liked, I would form that into a working script for Craig, and he would look it over and do rehearsal. I worked fifteen hours on a good day.

Smithberg: Our pitch meetings were so great.

Unger: We brought a woman [into Madeleine’s] office who had finally nailed [creating] a diaper for her dog. She was this eccentric French woman and we interviewed her [with] a stuffed German Shepherd and quizzed her about how much poop she could get into the diaper. People are locked into a reality and, like horses with blinders on, they don’t see anything else. That was my biggest revelation: you can come at people with any question when they’re really narcissistic or self-obsessed. But when people write about The Daily Show and its arc, it’s a misnomer to think we picked stories to make fun of people who weren’t “newsworthy.” We were experimenting with the form of news. It really wasn’t about those people; it was, “How do we make this about ourselves?”

Smithberg: We were always the idiot.

Grenrock-Woods: But there was a doctor who was convinced that, every night, he would be called up to a spaceship and [together with the aliens] would anally impregnate various celebrities. I had come up with a dream list of celebrities, and when he started naming all the Golden Girls, I said, “I’m fucking in!” I felt like I had struck gold.

“We were always the idiot.” — Madeleine Smithberg

DeGeneres: My first piece was in Saskatchewan, and it was about an old guy who didn’t follow The Farmer’s Almanac and instead forecasted the weather by licking fresh pig spleens. I had a great time shooting it.

Littleford: We weren’t trying to pin anyone against a wall. We could just go to uncomfortable places where the person was comfortable. I did two pieces in Vegas in one day, one on midget cannonballs and one on a Miss America rodeo. The camera has a lot of power. As long as we could pretend we were some kind of authority, and ask our questions with authority, they would answer.

The No Spin Zone

Littleford: When Jon took control of the whole show…it had become very political on a national scale, and because of Jon’s voice, correspondents were sent to do bits that were written for them, and Jon dictated what he wanted.

Havlan: Jon’s early shows are like the other shows, but it wasn’t long before it became more focused. He wasn’t afraid to say, “Let’s not call it ‘Headlines’ anymore.” Other news segments also went away. But Jon was very good at not [just] making changes for change’s sake, not making too many changes at once or forcing them overnight. He didn’t say, “We’re never going to write another pop culture joke.” But he eventually wound up on the cover of Time magazine.

Winstead: Jon asked me to come back twice, but I felt like he wasn’t going to have any problem carrying the show forward. I wanted to be able to create other franchises that were different from The Daily Show but [still] used humor to speak truth to power.

Smithberg: The moment The Daily Show became “The Daily Show” was the 2000 election. We had a live election show from 9 to 11 [that night], and at, like, 10:35, Florida flipped, and then we went into thirty-six days of not having a president[-elect] and hanging chads. By day fourteen, the “real media” did not know what to do, and they would use our clips [because] we dealt in absurdity and were the only ones who could make sense of it.

Unger: And before that, I’m not sure we could’ve filled the show with any more politics. We were proportional to what the media shows were filling at the time. It was mirroring the times, and the media landscape changed. And once the three major networks started fighting for ratings…

Smithberg: …it was like fish in a barrel.

DeCaro: It was like satirizing news in the beginning, but then it became the news. [More] people started getting their news from The Daily Show.

Havlan: After the 2000 election, we realized that we could dig into the Iraq War and didn’t have to be dependent on the content of the story, but on how it was being covered. I knew our show was doing well when we won our first Emmy in 2001. I said, “I guess this is going to go on forever.”

Grenrock-Woods, Unger, Smithberg, and DeCaro photographed at FLOOD Gallery in Los Angeles by Rozette Rago

Last Week Tonight

Grenrock-Woods: When the show got more political, it sucked for me because I was doing human interest stories, although I managed to keep them going for a while.

Winstead: I wish the old episodes were up [on the Comedy Central website] so we could see the evolution of the show. There’s a great clip called “Model Olympics,” in which Donald Trump has models on the beach doing bean-bag races and other ridiculous tests.

DeGeneres: I know for a number of years the Daily Show website had most of the segments. It would be great to get those old pieces out there.

Littleford: I’m not sure what happened to the first two and a half years of tape. I can’t find my David Cassidy interview, it’s gone. I heard that Jon donated that tape. It’d be very sad if they were lost or tossed.

Unger: I have heard three rumors: 1) that there was a fire and all the tapes were destroyed; 2) that they were erased because someone felt they were not important; and 3) they were intentionally destroyed. I would love to see some of those things thrown up on digital. The show has become an institution; they belong in a vault somewhere.

Grenrock-Woods: We demand to know where the tapes are! FL

Special thanks to original Daily Show Talent Coordinator Kate Post Spitser for her help with this story.

Archival photos courtesy of Comedy Central, Madeleine Smithberg, Beth Littleford, J. R. Havlan, and Vance DeGeneres. Archival Frank DeCaro portrait by Frank Veronsky.

This article appears in FLOOD 4. You can download or purchase the magazine here.