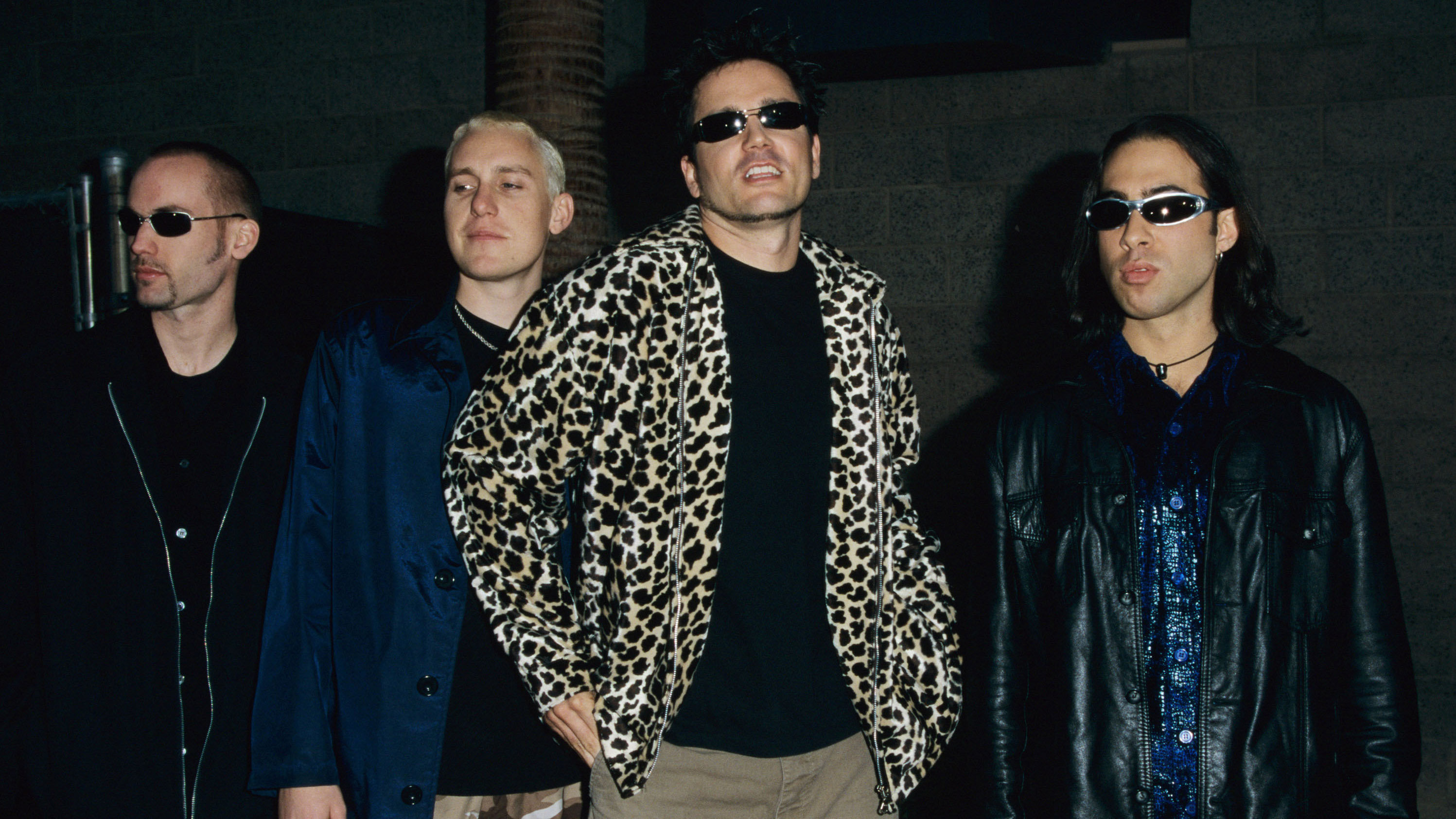

To millions who came into adolescence in the late ’90s, the names of the songs still jump off the page: “Semi-Charmed Life,” “Jumper,” “How’s It Going to Be.” The melodies still impart a longing sense of nostalgia. San Francisco band Third Eye Blind enjoyed half a decade of mainstream success with their six-times-platinum 1997 self-titled album and 1999’s Blue.

This summer has seen a resurgence in attention for singer Stephan Jenkins, who’s made headlines by reportedly rescuing paddle boarders in North Carolina, enraging Republican fans at a Cleveland fundraiser during the RNC, and following it up the next week with a Black Lives Matter song that perhaps didn’t quite get the reactions Jenkins envisioned. Not that it stopped the band from drawing one of the largest non-headlining crowds at Lollapalooza a couple of weeks later.

Of course, the band that stepped on stage at Grant Park isn’t the same Third Eye Blind that’s responsible for those hits. Infighting splintered Jenkins, bassist Arion Salazar, guitarist Kevin Cadogan, and drummer Brad Hargreaves years ago. What followed was firings, replacement members, lawsuits, courtrooms, and bitterness that remains to this day.

Third Eye Blind now has five albums to its name, including 2015’s Dopamine. But as the band nears the twentieth anniversary of its debut, now-former members Cadogan and Salazar have begun playing the songs they co-wrote at small clubs around the Bay Area. They say that has led to numerous cease-and-desist letters from Jenkins, who owns the trademark to commercial use of the name “Third Eye Blind,” and, according to previous lawsuits, has referred to other band members as contract employees.

“We are not trying to present our sides of a battle,” said Cadogan the day before a June concert in San Lorenzo, CA, advertised as “Original Members Of Influential 90’s Band Play Their 1997 Debut Album!” The two are planning a show celebrating the anniversary of the debut later this month at a popular San Francisco brewery.

“We just want to play our music.”

Cadogan left the band in 2000 after seven years, voted out by the three other members, including Salazar.

“I was being fed a line by everyone surrounding the band—management, lawyers, accountants—and so was [Hargreaves], about how Kevin was making trouble,” Salazar said.

“We are not trying to present our sides of a battle… We just want to play our music.” — Kevin Cadogan

As he explains it, Cadogan had found out that while the singer had told him and the others that they were equal partners in Third Eye Blind, Jenkins had filed for the band trademark in his name only and was in the process of securing sole copyright to all of the band’s songs, which were co-written by everyone.

“The first album featured ten of my songs, and the second, six,” Cadogan said. “That definitely didn’t sit well.”

Cadogan says that he was able to secure his own copyrights to his songs—the only other Third Eye Blind member to have any ownership.

“What they did subsequently to other band members is, they would take the copyright and make the band member feel like they owned their own songs when in fact they didn’t,” he said.

Tony Fredianelli, the guitarist who went on to replace Cadogan in the band, allegedly got much the same treatment before being fired in 2009. He sued Jenkins in 2011 and was awarded nearly half a million dollars.

Cadogan also sued the band, citing fraud, breach of contract, and wrongful termination. He eventually settled out of court. His payout was small due to statutes of limitations, he said.

Third Eye Blind’s first manager faced a similar fate. Eric Godtland was Jenkins’s friend. According to California Superior Court documents, the two met in 1991, and Godtland suggested Jenkins start a new band (at the time, Jenkins was in the hip-hop duo Puck and Natty). The documents say that Godtland personally financed the project, paid Jenkins’s living expenses, and helped write songs. He incorporated the band in 1996, with all shares going to Jenkins, and helped the band land a deal with Elektra.

In a recent call, Godtland said working with Third Eye Blind was the most difficult experience he has ever had as a music professional.

“Other industry professionals around me…would tell me just how bad I had it,” he said. “It was a difficult situation all the way around… I think Stephan in particular was pretty selfish.”

Godtland says the major rift between Cadogan and Jenkins began over whether the other original members agreed to give Jenkins final say in creative and business decisions. He said he was not involved in filing for a trademark on the band name.

“I think [Jenkins] discovered that he didn’t have a trademark on the name sometime later down the road and had it done,” Godtland said.

“I was being fed a line by everyone surrounding the band—management, lawyers, accountants—about how Kevin was making trouble.” — Arion Salazar

In 2008, Jenkins fired Godtland and sued him, saying he was not getting paid enough. Godtland counter-sued, alleging that the band breached its contract and Jenkins put his own interests ahead of others, creating a lack of productivity and a loss of finances for himself and the group. According to the countersuit, Jenkins withheld payment from Godtland until Godtland allowed Jenkins to get a larger share of profits for himself and distributed less to the other band members.

Jenkins’s suit was eventually dismissed. Godtland settled.

The former manager said he stuck with the singer from the very beginning to the point when he was left high and dry.

“[But] I always knew what kind of guy I was dealing with,” Godtland said. “Somebody who was self involved and narcissistic.”

After Godtland was fired, Jenkins offered the job to tour manager Bobby Schneider, said Schneider, who had been with the band since 1997. Instead, Schneider quit. Later Jenkins accused him of stealing the band’s equipment, he said.

“My exit was not good,” he said. “He was an asshole.”

A representative at the band’s current label, Megaforce Records, declined comment for this story. Numerous calls and e-mails to Jenkins’s attorney were not returned. E-mails to Third Eye Blind’s current publicity team were not answered either.

Salazar left the band after one more album cycle, surrounding 2003’s Out of the Vein. By that point, he also had become disillusioned. He says he wasn’t even allowed to keep some of his bass equipment when he left the band, an accusation backed by Schneider; Jenkins allegedly claimed it as his own. Salazar, meanwhile, continued to feel bad for his role in Cadogan’s ouster.

And then, in 2011, the two East Bay residents ran into each other at a DMV office. Cadogan invited Salazar to play some of his original songs with him at an upcoming show.

“At that point I hadn’t played music at all in two years,” Salazar said. “It was a really big deal because he got me to play music again.”

For that show, Cadogan and Salazar included in their bios that they were original members of Third Eye Blind. Soon after, they say they received their first cease-and-desist letter from Jenkins, who had a problem with any use of his band’s name for a commercial purpose.

They say they’ve continued to receive such notices for most of their shows. Most recently, Jenkins and Third Eye Blind successfully lobbied ticket service Eventbrite to remove all mentions of the name off the Cadogan Salazar (as the duo is calling themselves) event listing in June.

“It really is as simple as ‘we wrote it, it’s our music, it’s a part of our legacy.’” — Arion Salazar

“Due to a trademark violation complaint we received, we were obligated to remove all references to ‘Third Eye Blind’ from the event listing,” Eventbrite spokeswoman Amanda Livingood said. “Eventbrite performs legal analysis on a case-by-case basis. In this case we concluded that the removal was appropriate.”

Cadogan called the cease-and-desist letter to Eventbrite silly and an extension of Jenkins’s harassment.

“Jenkins is threatened by us, and you can see that it’s a competition to what he’s presenting to the public [of] what Third Eye Blind is,” he said.

Cadogan Salazar shows typically consist of newer material along with a Third Eye Blind album played from start to finish. Between playing those songs, the two tell stories, rarely referring to Jenkins or mentioning his name.

“The only other time Third Eye Blind played the first record from start to finish was on the first tour,” Salazar said. “There’s a lot of songs we’re playing that people haven’t been able to see live…by any version of Third Eye Blind since 1998.”

Trademark law is firm regarding use, but it gets stickier when no legal agreement is in place, and it’s often judged subjectively by courts. Federal trademark protection gives the owner of the mark exclusive rights to its use for goods and services that it represents, said Erin M. Jacobson, a music industry attorney based in Beverly Hills. Whether Jenkins can stop Cadogan and Salazar from using the name depends on aspects as diverse as the size of the type on a poster, how they use the name, and whether there is any chance of people being confused by that use, she said.

“If someone buys a ticket thinking they’re seeing Stephan but they’re seeing the other guys, then they’re being misled,” Jacobson said. “They can’t profit off it.”

Cadogan and Salazar insist they’re not trying to take any money or fans away from Jenkins and Third Eye Blind.

“It really is as simple as ‘we wrote it, it’s our music, it’s a part of our legacy,’” Salazar said. “We aren’t getting rich doing it… There are young fans who are probably just starting to realize there were original members that played and made the records that built the foundation and gave the band a career. I like the idea of people getting to learn the history of the band.”

They have no intention of giving in, either, and believe they’re just as entitled to the early Third Eye Blind songs as Jenkins. They’re proud of their accomplishments with the band. Cadogan and Salazar hope for a peaceful resolution with Jenkins that would allow them to use Third Eye Blind’s trademark, but they don’t predict reconciliation or ever again sharing the stage with their former bandmate.

“What we’d like is to live and let live, ideally, and we’d like to stop being harassed by him,” Cadogan said. “Taking the name for himself, taking all the shares of a corporation. Pieces of paper [were] created to cause problems, and there are pieces of paper that can be created to fix problems, I suppose. But certainly the damage is done there.” FL

This story originally ran on the writer’s website.