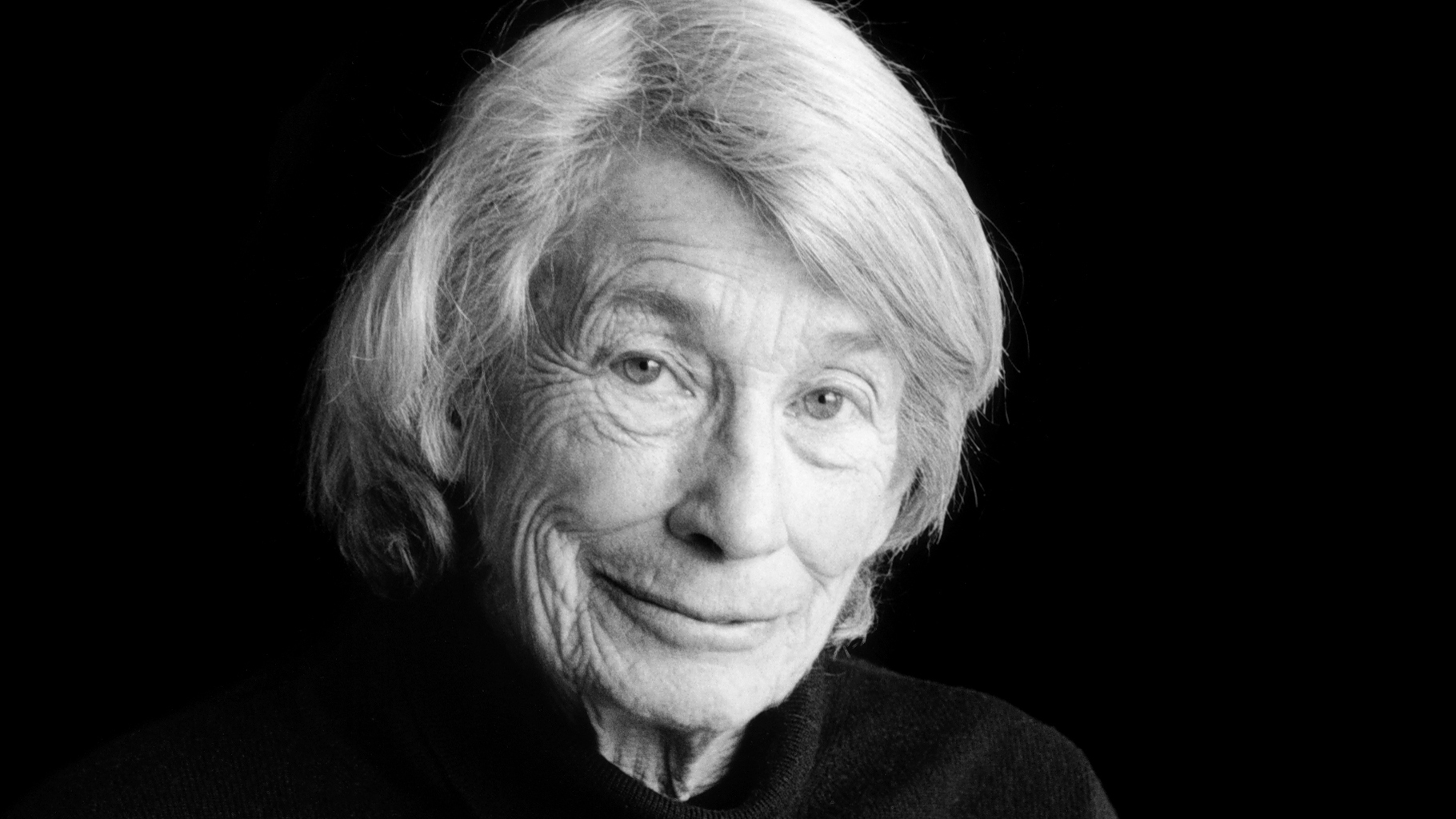

In an essay called “Swoon,” the poet Mary Oliver sees a spider. And it’s not a one-time sighting, either, but a relationship that grows and deepens, moving from trepidation into precise, specific knowledge. Over the course of several days, Oliver observes the shape and dimensions of the spider’s body, so perfectly defined for the laborious work of web-spinning; she notes not only the spider’s dietary habits but also her relational ones. She watches keenly as egg sacs hatch and spill open with a flood of new spiderlings. Oliver describes the physical motion of these hatchlings as though describing the kinetic poetry of a ballet.

Midway through the piece, she arrives at an acknowledgement that yes, this is where most such reflections offer up something like a “moral,” the point where we finally see the utilitarian import of what Elvis Costello might call all this useless beauty. And the great poet shrugs and says that she really has none, and indeed has nothing save for her own curiosity and awe. And this is enough, she suggests, enough to justify the disciplined observance of spider hatchlings, enough to justify the entire pursuit of poetry: it broadens our capacity for marvel. It makes our world bigger—“different, and more,” she offers.

In its act of wonder and its elevation of looking closer to the realm of sacred work, “Swoon” is the Upstream essay that proves most analogous to Oliver’s poetry, so beloved by so many, collected in a number of slender but essential volumes—Blue Horses and Felicity being two personal favorites. Oliver’s verse is often simple in construction but deep in its implication; it sketches clear evocations of the natural world but refuses to put a frame around the picture, leaving each piece open to abiding mysteries of life and love and death.

In its act of wonder and its elevation of looking closer to the realm of sacred work, “Swoon” is the Upstream essay that proves most analogous to Oliver’s poetry, so beloved by so many, collected in a number of slender but essential volumes—Blue Horses and Felicity being two personal favorites. Oliver’s verse is often simple in construction but deep in its implication; it sketches clear evocations of the natural world but refuses to put a frame around the picture, leaving each piece open to abiding mysteries of life and love and death.

This non-fiction prose collection gives the reader a chance to understand how these stylistic traits are habits of being for Oliver; though structured as brief essays, many of these pieces read with the same spirit of patient observation that makes her poetry special. It also gives Oliver a chance to stretch herself and to offer some pieces that are different both in genre and in tone from her more famous work, with a handful of these selections being almost explanatory in their nature.

That’s especially true of a middle section of the book, which we might call the “literary criticism” section. Here Oliver guides the reader through an appreciation of some of her own great inspirations—Poe, Whitman, Emerson, Wordsworth—and does a commendable job of capturing the spirit of each, even if some of these pieces, like the Emerson one, feel a little perfunctory, entirely introductory in nature.

Even better are a few essays that offer insight into the creative life, though not in a didactic way; the title essay is charming for how graciously it moves from personal travelogue to artistic manifesto, Oliver remembering girlhood walks in the woods and marveling at how foundational they remain for her, how important they still are as creative sustenance. And then at the end comes an admonishment: “Teach the children. We don’t matter so much, but the children do. Show them daisies and the pale hepatica. Teach them the taste of sassafras and wintergreen.”

Upstream sketches clear evocations of the natural world but refuses to put a frame around the picture, leaving each piece open to abiding mysteries of life and love and death.

This point offers a chance to glancingly compare Oliver’s approach with that of Marilynne Robinson, whose own When I Was a Child I Read Books is a peerless collection of essays about (among other things) education as a centerpiece of public life and policy. Robinson’s essays are dense and scholarly, though, something Oliver’s never are. Hers read more like dream journals or notebooks from a nature walk; they are seductions rather than arguments, and in their way they are just as persuasive.

But the true riches of Upstream are the pieces that find Mary Oliver just being Mary Oliver. I’ll mention just two more favorites: “Bird” is a hypnotic vignette about a wounded fowl that Oliver and her lover welcomed into their home and kept alive as long as they could; whether they were right or wrong in interfering with nature’s work (for without them, the bird would surely have died almost immediately) is the essay’s unanswered and unanswerable question. And in “Building the House,” she sets down her poet’s tools for actual brick and mortar, recounting her experiences in construction and contrasting this tangible craft with the more mystical trade of the writer.

“I built it to build it” she says of a physical structure she constructed but inhabits no longer; in much the same way, her essays—like her poems—seem to exist for nothing but their own pleasure, though they provide shelter and a privileged view for as long as we need them. FL