Staged in the intimate confines of the New York Theatre Workshop on an Off-Broadway side street in Manhattan, the mournful tale that was Lazarus—the continuing saga of emotionally impotent astronaut Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien/man stuck metaphorically inside a tin can, as one of the play’s authors once wrote—unfolded with the morbid energy of a weird funeral pyre.

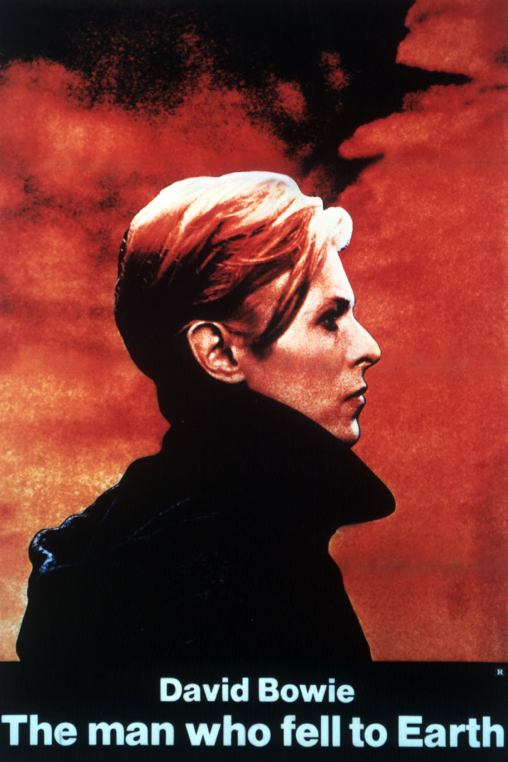

Penned by David Bowie and famed playwright Enda Walsh, Lazarus followed in the melancholy footsteps of its father film, Nicolas Roeg’s seminal, time-and-shape-shifting 1976 classic The Man Who Fell to Earth. Lazarus allowed itself to soak its extraterrestrial troubles in gin and swim in soapy milk while psychically sailing to a sad yet utterly fulfilling denouement—fitting, of course, as this and the January 2016 album ★ (a.k.a. Blackstar) would feature as Bowie’s final works.

While Lazarus prepares for a London run, The Man Who Fell to Earth is being re-released globally in cinemas and on Blu-ray with a new 4K print just in time for its fortieth anniversary. Also seeing light for the first time is the never-before-issued soundtrack, which was penned and produced by the late John Phillips (of The Mamas & the Papas) with the aid of one-time Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor and famed pedal steel player B. J. Cole.

The Man Who Fell to Earth is not simply an acting triumph for Bowie and his co-star Candy Clark; it’s also an aesthetic victory for director Roeg, cinematographer Tony Richmond, and editor Graeme Clifford (the team that crafted 1973’s magnetic Don’t Look Now and its splinted tale of careening grief and psychic phenomena). Their time-shattering, flashing-forward vision of a verdant American landscape that stretches from New Mexico to Los Angeles lives beyond our galaxy, as did the film’s protagonist. In the titular role, Bowie’s portrayal of Newton’s alternating senses of hope, loneliness, and despair drew cinemagoers in closer to the man himself—much as his mere casting worked to draw crowds, period.

“The camera absolutely loved him—that pasty, pale, translucent skin; that red hair; those eyes and cheekbones,” says Richmond.

When Roeg was an industry-famed cinematographer in the ’60s, Richmond was a young cameraman just starting out in the biz. Together they worked on 1965’s Doctor Zhivago, 1966’s Fahrenheit 451, and 1967’s Far from the Madding Crowd. “We became great friends; still are, really,” says Richmond, knowing that, for now, he is speaking for Roeg on all matters Man Who Fell to Earth, as the director is ailing. “We all get old,” he adds regarding his friend.

The Man Who Fell to Earth moves at blinding speed, both cinematically as a boundary-breaking film and thematically as a story fractured without warning. It bounces between an alien-turned-billionaire’s journey to Earth in search of life-saving resources and the future of his two families (the one here and the one beyond this solar system), both seemingly fraught with gloom and frustration.

“I know good writing when I read it, and I could visualize this straight away,” says Candy Clark, who got the Man Who Fell script early on from Roeg for the part of Mary-Lou. The actress was a solidly inventive, up-and-coming model turned thespian who had been nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for American Graffiti a few years prior. At the time, the director was still only considering the project from Walter Tevis and Paul Mayersberg, the author of the novel and the film’s screenwriter, respectively. “I never asked if financing was in place,” says Clark. “I was just pleased to have it offered to me without having to audition.”

Richmond considers himself a slave to the story as well as a director’s vision. Roeg advised him to let a script dictate the style of photography he’d execute, rather than trying to impose his own aesthetic will. Preferring to work for independents rather than big studios (“the studios want things bright, without texture or nuance”) made them natural collaborators on The Man Who Fell’s New Mexico set.

The film’s paradoxically earthen yet star-bound look—clouds that hover overhead for hours, deep azure blue skies—are owing to the fact that most of Roeg’s completely British crew had never before experienced American vistas. “We were filming in [the US] for the first time and there was this massive amount of amazement,” laughs Richmond. “Everything was so new.”

That vision of the new is as good a point as any for David Bowie’s entrance. While Paramount boss Barry Diller wanted Robert Redford for the role of Thomas Jerome Newton, Roeg pushed for Michael Crichton, the impossibly tall novelist whom the director best believed resembled the lanky giant in Tevis’s novel. When neither came to pass, Peter O’Toole was considered—until Roeg caught Bowie in “Cracked Actor,” a 1975 episode of the British documentary series Omnibus, where the lean singer sniffed and mumbled his way through limo rides and backstage confabs until he hit the stage.

That vision of the new is as good a point as any for David Bowie’s entrance. While Paramount boss Barry Diller wanted Robert Redford for the role of Thomas Jerome Newton, Roeg pushed for Michael Crichton, the impossibly tall novelist whom the director best believed resembled the lanky giant in Tevis’s novel. When neither came to pass, Peter O’Toole was considered—until Roeg caught Bowie in “Cracked Actor,” a 1975 episode of the British documentary series Omnibus, where the lean singer sniffed and mumbled his way through limo rides and backstage confabs until he hit the stage.

Bowie was alive with alien grace; he was an unproven talent as an actor, but certainly a presence. “I wasn’t a Bowie fan to begin with, or into the whole glam rock thing,” says Clark. “I was into Marvin Gaye and soul music, and besides, going to concerts killed my ears.” However, the actress did see Bowie in D. A. Pennebaker’s Ziggy Stardust documentary and thought he was interesting. “I’m glad now that I hadn’t seen him in concert until after we filmed together. It would have spoiled our acting relationship,” she says. “I think I would’ve been too goo-goo-ga-ga over him. When I did see him perform, by his invitation, I immediately became a [devotee].”

At that point, Bowie had his eye on film. As he penned the Diamond Dogs album, he also famously wrote a film treatment of its apocalyptic tale to star Terence Stamp and Iggy Pop. Didn’t happen. At Elizabeth Taylor’s urging, he was in talks to co-star in The Blue Bird. Didn’t happen. There was a modern Around the World in 80 Days script co-written with Flo & Eddie that he was set to direct. Didn’t happen. He was asked to co-star with Richard Burton in The Eagle Has Landed. Didn’t happen. Only the urging of his then-agent Maggie Abbott and Roeg’s fascination with the “Cracked Actor” doc pushed Bowie to the filmic fore.

“As soon as Bowie got to New Mexico, he was the man who fell to Earth,” says Richmond. “There were times when you felt as if he was just [barely] holding it all together in his daily life, but he made that work.”

Clark believes Roeg chose Bowie because the singer was used to stopping and starting during the middle of takes in the studio to get things just right. “David loved running lines over and over from top to bottom between scenes,” she says of a rehearsal schedule and budget that did not allow for table reads. “He never griped about stopping a scene in the middle and picking it back up with a certain line, because that’s what he was used to doing during recording sessions. He wasn’t ever precious about it. That wasn’t David.”

Where Bowie did tense up, oddly enough, was during one of the film’s three nude scenes—the most gentle, romantic one, according to Clark. “We’re supposed to be precious—all young love and natural—but we’re naked in front of a crew of people. It was mandatory throughout the 1970s. I felt as [though] he was uptight,” she laughs, recalling that when the two had to perform a nude scene after her character had aged some forty years, Bowie was less reluctant. “Oh, when they brought in my sixty- or seventy-year-old body double, he was all over her, really into that, down there licking. Loving it really. Maybe he was just uptight with me.”

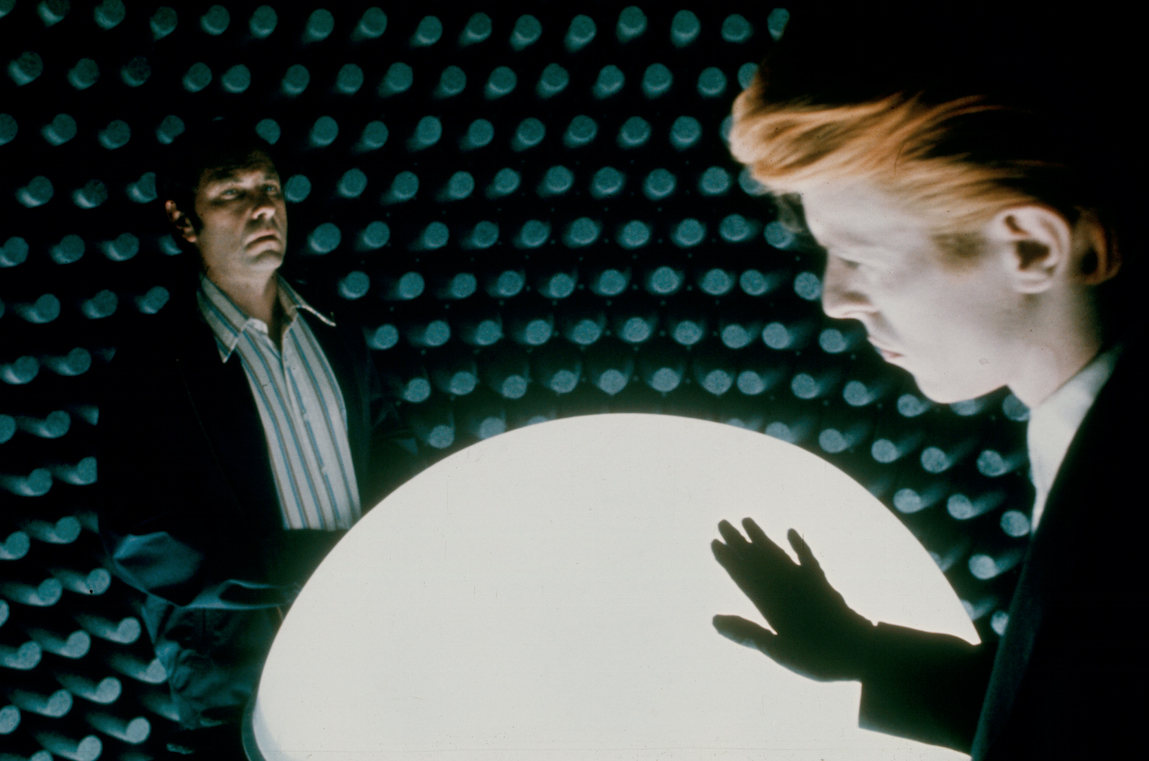

While Clark mentions their poignant breakup scene as her favorite of the film (“Nic’s only direction was to remember that this was the last time I would ever see [Newton]—that choked me up”), Richmond picks a more iconic image: the one that provides the cover of Bowie’s 1976 album Station to Station. “That scene where we used this simply designed white spaceship, spare lighting, and David and Rip Torn talking about space travel versus weaponry is dazzling to me—funny, too. When Bowie asks about being an alien and Rip asks if he’s from Lithuania, I still laugh.”

What was no laughing matter to the filmmakers was how the film, upon its original US release, got hacked up by its distributors for no good reason other than to accommodate more screenings. “Am I upset that the American version was chopped?” asks Richmond. “Yes, unabashedly. They butchered it. Those idiots didn’t get it. That’s why we made sure to get [the new 4K restoration] right. We got the colors on this new one closer to the original film, more lustrous yellows and shadows.”

What was no laughing matter to the filmmakers was how the film, upon its original US release, got hacked up by its distributors for no good reason other than to accommodate more screenings. “Am I upset that the American version was chopped?” asks Richmond. “Yes, unabashedly. They butchered it. Those idiots didn’t get it. That’s why we made sure to get [the new 4K restoration] right. We got the colors on this new one closer to the original film, more lustrous yellows and shadows.”

The film’s soundtrack was similarly fraught. It was originally to have come from Bowie himself, who intended for the project to be his follow-up to 1975’s Young Americans. Arranger Paul Buckmaster worked with the musician on a score featuring bits of music that turned out to be little more than unmixed, bluntly edited instrumental tracks, discordant electronic cuts, and African thumb piano suites.

“Bowie had been doing stuff for over three months in Bel Air and Cherokee Studios in Hollywood, and Roeg was getting impatient, especially as his editor was clamoring for product and the tracks that he had received weren’t yet mixed,” says writer Chris Campion, who is currently working on a biography of John Phillips. “It hadn’t even been timed or synced to any of the scenes in the film.”

It’s been rumored that the five or six songs Bowie composed were a mess, that his contract to score the film was botched, and that he had perhaps devoted too much of his post-filming time to completing Station to Station. For now, those songs remain a mystery; the music is sealed in a vault and will only be released if Bowie’s estate allows.

Either way, Roeg ditched Bowie’s efforts for those of Phillips. In 1976, Phillips was still a remarkably productive musician and composer who happened to be a longtime pal of Roeg’s. “They knew each other from the clubs of New York City and Roeg thought of Phillips—certainly a character but a capable one—as the perfect man to score his film,” says Campion. “Roeg wanted American music, and he knew that Phillips was steeped in folk, ragtime, blues, and country.”

Either way, Roeg ditched Bowie’s efforts for those of Phillips. In 1976, Phillips was still a remarkably productive musician and composer who happened to be a longtime pal of Roeg’s. “They knew each other from the clubs of New York City and Roeg thought of Phillips—certainly a character but a capable one—as the perfect man to score his film,” says Campion. “Roeg wanted American music, and he knew that Phillips was steeped in folk, ragtime, blues, and country.”

Bowie’s music would surely have been intriguing, but it might have been an obvious way to go considering that most alien-oriented films would use such a spacey score. “What was brilliant about Roeg is that his brief totally went against expectations,” notes Campion. “What would be more alien to a visitor—and more quintessentially American—than bluegrass, country, and folk? That would all be part of the information overload that Bowie’s Newton character was receiving from radios, television, and alcohol consumption.”

Richmond agrees, stating that though Roeg knew exactly what he wanted for The Man Who Fell to Earth, he was an organic director content to let his actors fly and the ambience of the moment have its way. “Best I’ve ever worked with, and that film is the best he ever made,” he says. “There are no storyboards with him, no shot lists, [he] just let things play. We need more films from him.”

For now, The Man Who Fell to Earth, as a full package of restored sound and vision, will have to do. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 5. You can download or purchase the magazine here.