It was the pull quote heard ’round the world. “I am ready to die.”

Admittedly, it has a certain zing to it. And as Biggie knew, it’s a pretty undeniably badass stance to take. But when those five words spread around on social media last month, they were missing the point.

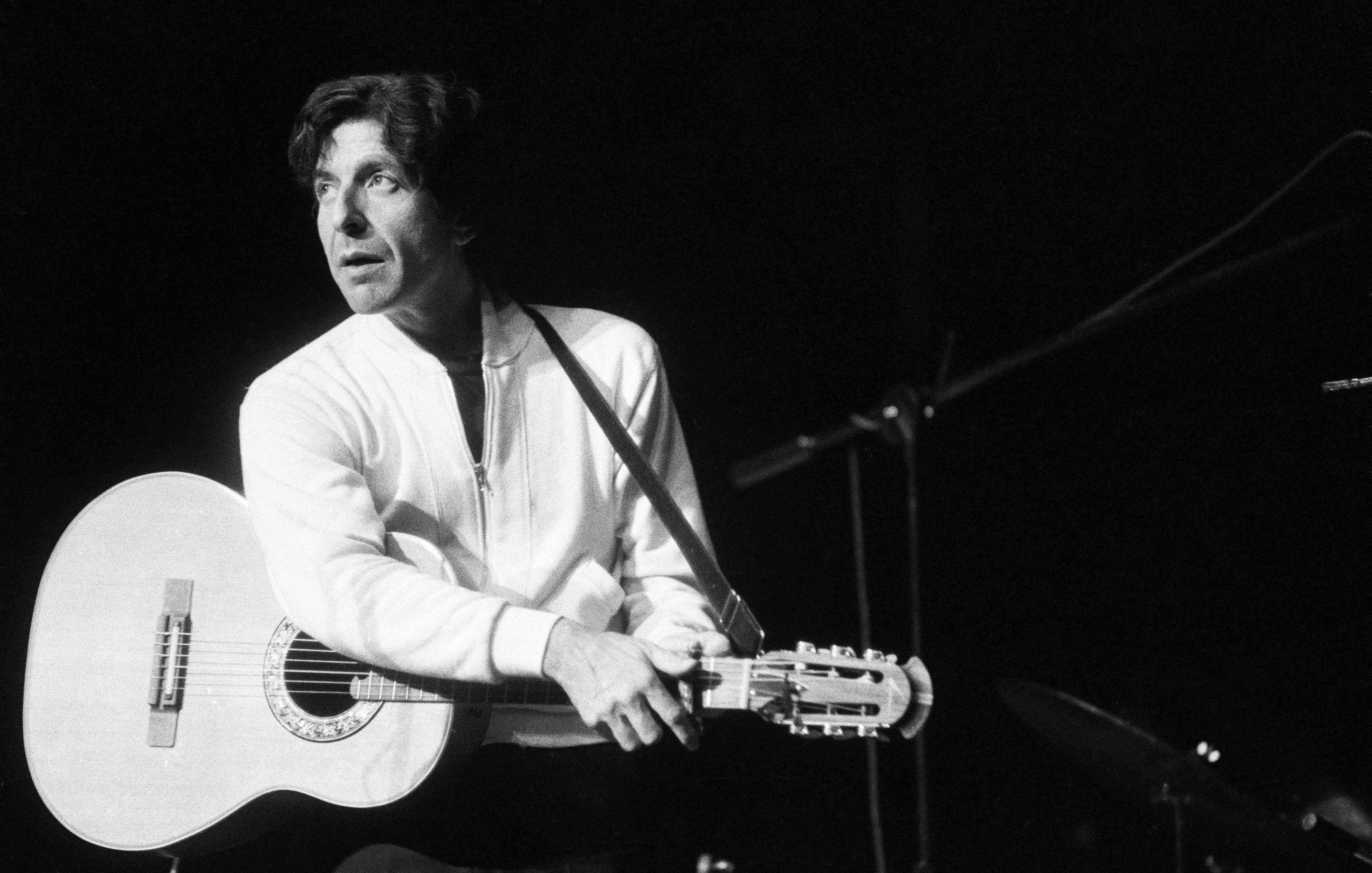

As Steven Hyden wrote recently for UPROXX, Leonard Cohen came out of the womb ready to die. That fact was tied to the whole essence of him—that he was spiritually engaged at the highest level, that he was a seeker. In that regard, Cohen was no more concerned with death than he was with life. It’s just that in his journey to seek answers, he was never afraid to ask the darkest questions of our existence. And clearly, in the end, we did indeed want it darker—and Cohen delivered.

You Want It Darker is, naturally, an album that deals deeply with death. But it isn’t an album wholly focused on death—and for the most part the death inside doesn’t even seem to be Cohen’s own. For my money, anyway, the extinguishing candle consistently referenced within seems more likely to belong to Marianne Ihlen, his longtime muse, who died earlier this year (following one last heartbreaking exchange with Cohen on her deathbed). Regardless, though, I am highly skeptical of the predominant interpretation of this album, in which it is viewed as the outgoing statement of a terminal man.

This suspicion was further validated by the news last week that Cohen’s death was not due to some drawn-out illness, but rather by a fall in the middle of the night. It was just an accident. To call You Want It Darker a deliberate parting gift is an arbitrary interpretation. Cohen was here, he made the album, and then he died. That’s all we can concretely say.

And yet, it’s certainly too perfect an ending to ignore. Whether by design or not, the album does serve as a career-encapsulating bow, itself rivaling Blackstar (a.k.a. ★), David Bowie’s unreal departure, which was definitively conceived and released as a likely final statement on life and death, celebrity and art. But when people look back—in either upcoming year-end lists or far-future retrospectives—it’s hard to imagine that Bowie’s release will not be the more revered artifact. Partially, that’s because Bowie was the bigger star, and partially that’s because the whole Blackstar package—from the music videos down to the album art—was a uniquely curated experience built for us to cope with losing him. Even though it’s somewhat unfair to outright stack up the two releases tit for tat, Cohen’s swan song simply doesn’t have that kind of firepower to it—and it didn’t help that his death was announced in the immediate aftermath of a devastating and highly distracting election.

To call You Want It Darker a deliberate parting gift is an arbitrary interpretation.

That’s a shame because, besides Cohen being infinitely more worthy of our attention than Trump (duh), You Want It Darker is actually a better album than Blackstar. In fact, it’s better than a lot of the truly great music that’s come out this year—and better than a good number of the works that Cohen put out over his own legendary career. Owing in part to the production work of Cohen’s son, Adam (who worked alongside his father and Patrick Leonard), the album is bursting with emotion, but delivered with composed exactitude. Measured in style, but lush in arrangement. In a word, it’s essential. And if it’s a goodbye, it’s sublime. But most of all, if it’s a horse in a race, it’s destined to be the one wearing the sash.

In David Remnick’s now-definitive New Yorker portrait of Cohen (from which the aforementioned “ready to die” quote was pulled), there’s a story about Bob Dylan. According to Cohen, the two were driving together, telling stories, when Dylan told him of a recent compliment he had received from a famous songwriter, who said, “Bob, you’re Number One, but I’m Number Two.” This led Dylan to compliment Cohen (in his own way), saying, “As far as I’m concerned, Leonard, you’re Number One. I’m Number Zero.”

It’s hard to imagine a better anecdote to encapsulate the fifty-year musical career of Leonard Cohen. Even when he came in first, he still couldn’t win. But that’s fine. He was Our Man—our Field Commander Cohen—precisely because of how he tossed the power rankings aside and soldiered on. Year by year. Month by month. Day by day. Thought by thought. FL