Barry Moser’s We Were Brothers is a book about many things, none of them easy to swallow. It’s a book about the fracture we all share as human beings, and about a particular rift that exists between two brothers. It’s a book about racial prejudice as our American birthright, and about reconciliation as something elusive and hard won.

But here is the hardest one of all: We Were Brothers is a book about loving our enemies—never an easy mandate, and perhaps never a less welcome one than in the dawning days of Donald Trump’s America.

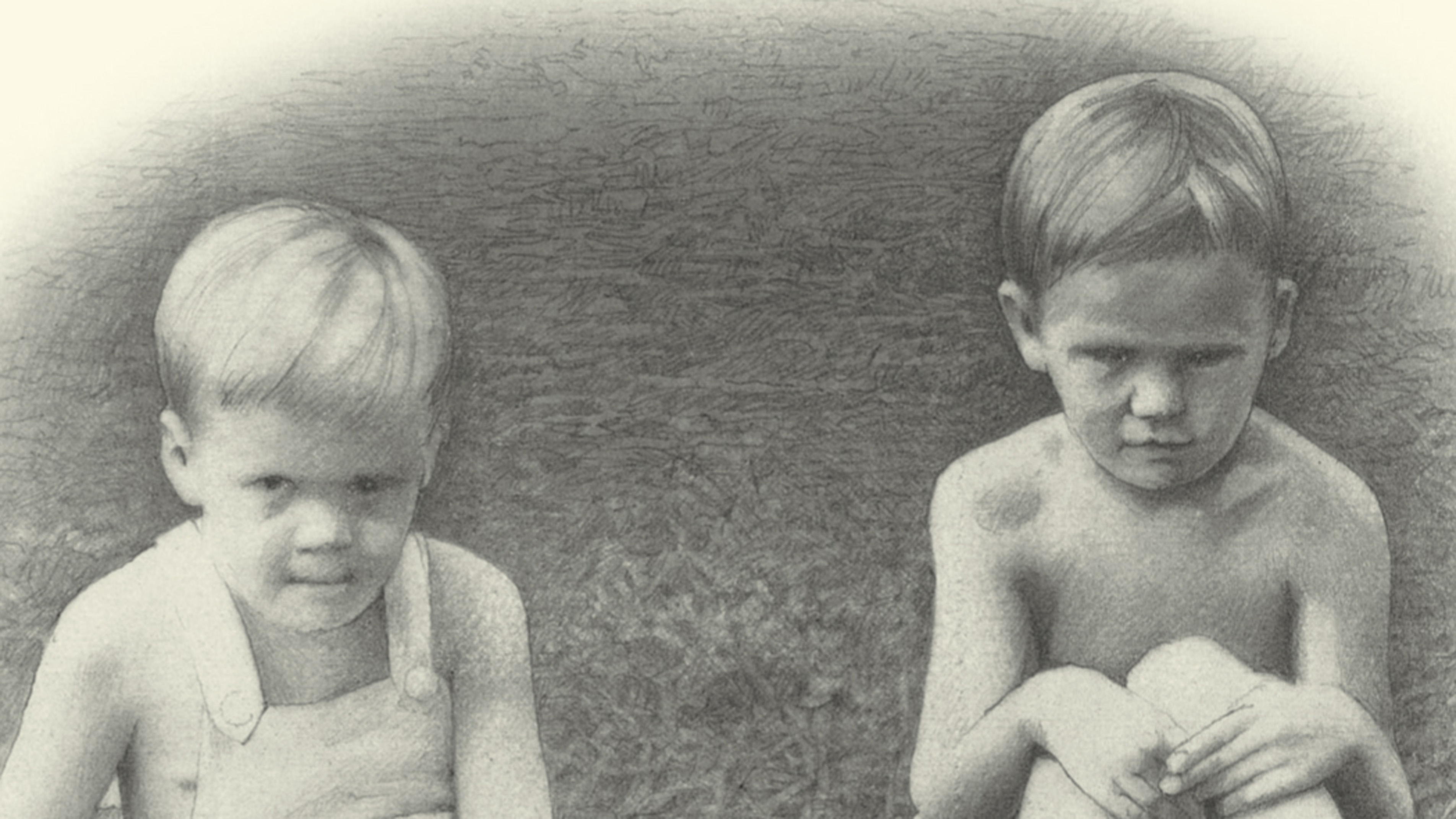

A reflection on Moser’s childhood in the Deep South—he was raised in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and by his own admission he was born into a deeply racist family and worldview—the book’s sociopolitical remembrances are all offered as a way to understand the estrangement the writer felt from his brother Tommy. Tommy is portrayed in the book as someone of profound ignorance and hate; Barry, conversely, is the brother who was fortunate enough to receive enlightenment and education, to become a recovering racist and a passionate spokesperson for justice and equality. (In addition to being a fine writer, Moser is also a printmaker, illustrator, and teacher.)

There are harrowing depictions of racism here, including one incident in which a young Barry’s family reverie is interrupted by the panic of their black neighbor. She has just heard that members of the KKK have committed an act of grave violence against another black family in town, and she is justifiably worried. The white members of the Moser family assure her that she’ll be alright—just so long as she remembers her place.

There are harrowing depictions of racism here, including one incident in which a young Barry’s family reverie is interrupted by the panic of their black neighbor. She has just heard that members of the KKK have committed an act of grave violence against another black family in town, and she is justifiably worried. The white members of the Moser family assure her that she’ll be alright—just so long as she remembers her place.

Of course she is meant to be a recipient of our empathy, and We Were Brothers may prove eye-opening to anyone whose comfortable life experience leads them to believe that reports of America’s historic racism are somehow exaggerated. They are not, and Moser respects the gravity of his subject matter enough to depict it using a suitably blunt, period-appropriate vocabulary. It is impossible to read these remembrances without experiencing active sorrow on behalf of the marginalized communities it depicts.

But here’s the thing: reading this memoir, I also found myself feeling a certain empathy for Moser himself, whose early attitudes about race he inherited and in some ways never stood much chance of resisting. I do not mean to diminish the wrongfulness of racism, or to allow anyone a way out, but when children are forced into the prejudicial mindsets of their parents, maybe they are victims of a different kind of violence.

For that same reason, I also feel a real compassion for Tommy. He is not made likable here at any point; Moser suggests that he regrets this, but must offer a faithful telling of their broken brotherhood, which sounds as though it was never anything but troubled. He never suggests, in all the exchanges he shares between himself and Tommy, that his brother was a secret saint with a heart of gold.

And yet he does suggest that Tommy—who died before this memoir was written—might have had his own story to tell; that he carried close his own brokenness and fear; that behind his hatred was real hurt. That doesn’t mean Tommy’s racism deserves to be excused or forgiven, and Barry doesn’t do either, but it does offer a possible way forward—if not for the Moser boys, then for us: true healing means showing love and empathy not just for the oppressed but for the oppressors; not only for America’s marginalized, but for Donald Trump, Steve Bannon, and anyone else whose hostility masks deep internal fissure. They are broken and may even be evil—but our hope lies in imagining that they may still dwell within redemption’s sway.

“If progress is really what we’re after, calling evil out for what it is can only be the first step in a longer journey of compassion.”

That’s not to suggest that white supremacy should be labeled otherwise, nor that bigotry’s rotten fruit should be coated in sugar; it is also not to suggest that we all simply hold hands and sing campfire songs with the oppressors. But I think Moser’s implication in all of this is that if you want to dissuade someone from racism, calling them a racist isn’t likely to do the trick. The argument is almost a pragmatic one: if progress is really what we’re after, calling evil out for what it is can only be the first step in a longer journey of compassion.

The final section of We Were Brothers is remarkable, and completely paradigm shifting. Up to that point, everything is presented in short-form narrative essays, each chapter a particular childhood memory that Moser recounts. Then he comes to a place where he reprints, verbatim, a series of lengthy letters that he and Tommy exchanged in the final years of Tommy’s life.

I can’t tell you anything too specific about the contents of these letters without spoiling their impact—but I’ll tell you that they hint at a side of Tommy Moser that we hadn’t seen before, and that even Tommy’s little brother seems disrupted by it. There’s not much that Tommy says that I agree with; much of it, in fact, strikes me as deeply ugly. But there is something healing and transformative in listening, and in remembering that his humanity is no more or less feeble than my own.

We Were Brothers emboldens that kind of listening. It dares to wonder what could happen when we attend to the earthy work of reconciliation—and to warn us that we don’t have forever to do it. FL