As espoused in the greatest short novel ever written, the world will always feel gutted at news of the death of a child; few don’t immediately grasp the significance of the lines “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” Thus when word came last summer that Nick Cave had lost his fifteen-year-old son Arthur in a horrible fall from a cliff in South East England, there came a collective gasp from those who had followed the prolific rocker during his forty-year career.

As a public figure who has featured continuously in the music press since the late 1970s, there was no way that Cave would be able to avoid having his family’s very personal tragedy reported on widely, and that he himself would not be asked to comment on it immediately and repeatedly—or so it would be assumed. Nick Cave had other plans.

Desperate to not subject himself to endless questions about the tragedy, Cave turned to what has always sustained him: his art.

One More Time with Feeling, a feature-length film in black and white and 3D, documents the recording of parts of Cave’s new album Skeleton Tree while also chronicling the Cave family’s emotional state soon after Arthur’s death. Both film and album are substantial artistic achievements.

Director Andrew Dominik has worked with Cave several times, most notably on 2007’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. The two are close, making Dominik something of a natural choice for a particularly unnatural project. Here, on the morning after the film’s worldwide premiere in September, the New Zealand–born filmmaker tells us about the delicate work of documenting the mourning process of someone you love.

You’ve had a professional relationship with Nick since 2000, when you used his song “Release the Bats” in your film Chopper. What’s your personal relationship with him?

Andrew Dominik: I’ve known him since 1986, [but] we’ve probably become [close] friends in the last fifteen years or something. We had a girlfriend in common. Do you know the song “Deanna” [from Cave’s 1988 album Tender Prey]? Deanna is the mother of my child; I started going out with her shortly after Nick. That’s how we got to know each other—he would call up to talk to her and we developed this kind of phone friendship.

A major part of the film’s appeal is technical, thanks to the cumbersome 3D camera that you built specifically for the project. I loved the shot where you wind down a hallway and then down a circular staircase. Was that done with that camera?

No, that was CGI. It’s actually an existing rig that holds two RED cameras, the supposedly handheld REDs that are thirty or forty pounds. The difficulties with the camera actually gave us a way in, as a kind of conversation starter; it would get people to talk to you.

This is the first black and white film you’ve released, and the first in 3D. Why try out those new techniques now?

I’ve been shooting black and white and taking 3D stills for years, so I was aware of the possibility of the medium to bring a kind of intimacy and claustrophobia to a film, as opposed to [the] spectacle [usually associated with 3D]—spaceships and such.

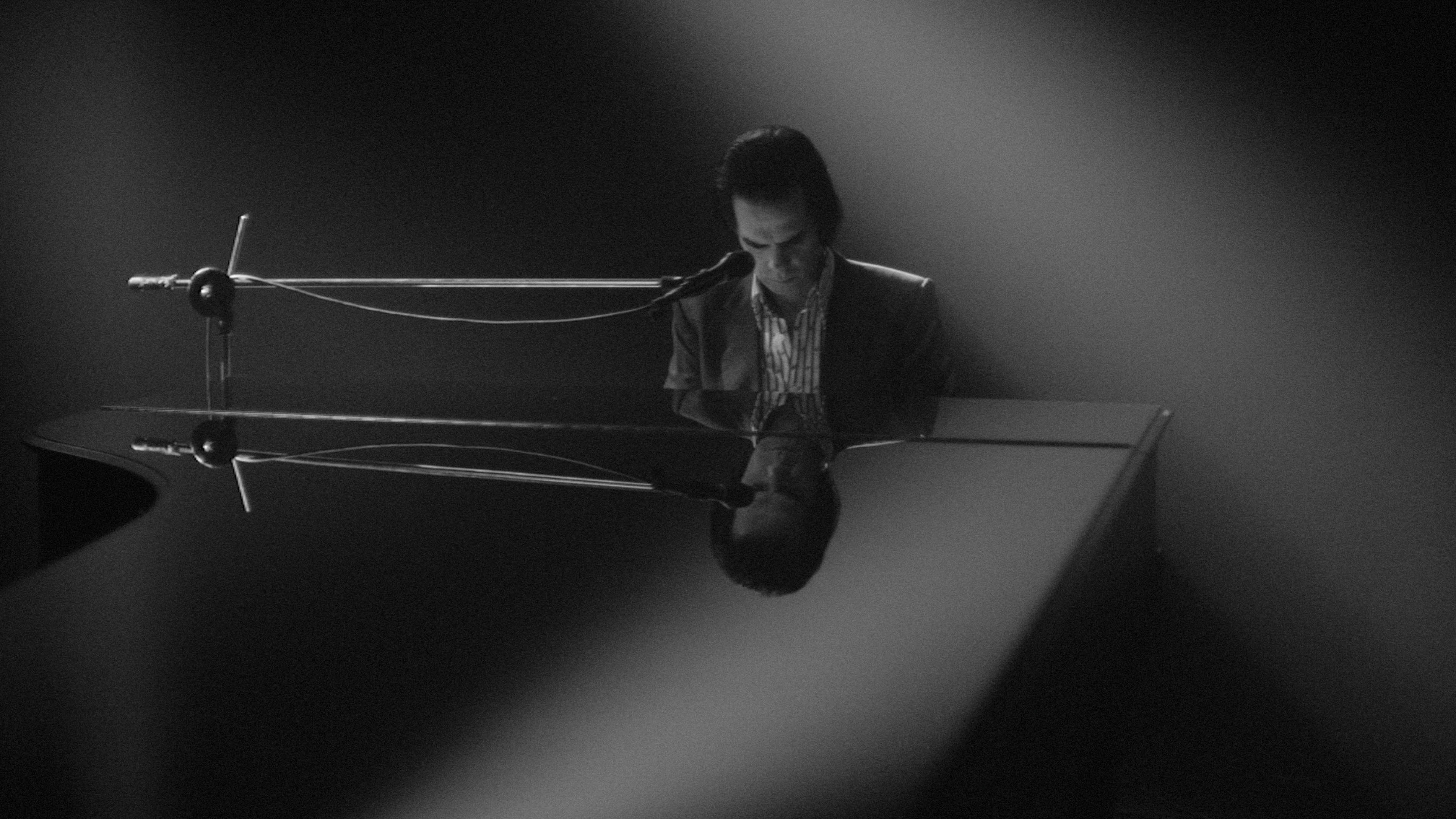

Nick Cave in One More Time With Feeling

Were you influenced by other music films? One More Time with Feeling reminded me of Godard’s Rolling Stones doc Sympathy for the Devil in parts; maybe the pacing is similar.

[D. A. Pennebaker’s 1967 doc on Bob Dylan] Dont Look Back was a big one. It’s black and white, it’s vérité, it’s set in London, it’s a portrait of a poet, it’s a bunch of fleeting moments. [Plus there’s the] stuff in the back of the cab. I stuck Nick in the back of a cab because I was always trying to put him in a situation where real life could intrude, to create situations where accidents could happen and it wasn’t so controlled. I thought if I kept him uncomfortable he would reveal more.

Did you notice his personality changing over this period?

I’ve always found Nick to be fairly open and fairly willing to talk about his crapulent self, and [currently] he feels diminished—“diminishment” is the word he uses a lot in reference to the blow that he’s suffered. There’s been so much going on emotionally for him. For the film I encouraged him to send me voice-over recordings of what he was feeling.

What was your strategy for using these recordings?

I didn’t want him to be too polished about anything. It was more important that he just send me a volume of material and then I could use bits and pieces of it all over the place. Then I’d take a piece of film and construct a poem, if you like, around it. He understood exactly what I was trying to do and was willing to send me stuff and let me monkey around with it.

Susie Bick, Nick Cave, Earl Cave, and Andrew Dominik on the set of One More Time With Feeling / photo by Kerry Brown

Arthur’s twin brother Earl is in the film briefly. It must have been intense to have such a vivid reminder of his brother there.

I thought that people would want to know what Susie [Bick, Cave’s wife of seventeen years] felt and what Earl felt. It was important to me that none of them were victims of the film; I tried to involve [Earl] early in the making of it by giving him the camera, giving him a way to provide his own comment. And to show Susie in her element; she’s a genuinely modest person and it’s really unusual to see someone like that in a movie.

Did you know Arthur well?

I wouldn’t say I knew Arthur well, but he was awesome. Both of those kids have a strong sense of self and are really good company. Arthur was the mouth and tended to do all the talking. He was daring and he was funny as hell and he was an experimenter and it was an awful fucking tragedy.

It must have been hard to tell at just fifteen, but did he seem artistic and apt to follow in his dad’s footsteps?

He used to make little violent home-invasion-type movies that were fucking hilarious. He was into magic, and you can hear him singing in the movie—he does the last song. I’m sure he would have left his mark on the world. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 5. You can download or purchase the magazine here.