Here’s a little story that must be told. When the Beastie Boys released Check Your Head on April 21, 1992, they weren’t sure whether they still had an audience. Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz, Michael “Mike D” Diamond, and Adam “MCA” Yauch signed to Capitol after their 1986 debut, Licensed to Ill, became the first hip-hop record to gun its way to the number-one spot on the Billboard 200. Expectations were understandably high. When Paul’s Boutique failed to do even a respectable fraction of its predecessor’s numbers in 1989, the label’s promotional wing turned its attention to Donny Osmond’s comeback record. The Beastie Boys were busted, and most everyone associated with them at Capitol was fired. The week after the album was released, Yauch, the group’s elder statesman, turned twenty-five.

It seems strange to think of Paul’s Boutique as a failure, even knowing its context. It is the mostly-agreed-upon gem of the band’s discography, a masterpiece of concept and execution that boils the Beasties’ exquisite record collection in a gonzo sauce of tossed-off references and passed-around verses. Like only a handful of other records in existence, one of its chief joys comes from thinking of how impossible it would be to make today.

But its greatest legacy might stem from its commercial failure. Suddenly liberated from expectations of any kind, Ad-Rock, Mike D, and MCA were free to pursue whatever they found interesting. The immediate result was Check Your Head, but the end result was something bigger: While they were creating the album, the Beastie Boys were also creating themselves.

261278-019-v3.psd

“We[’d] just made something we were very proud of, so we were crushed by the fact that nobody seemed into it,” Diamond says of the days after the release of Paul’s Boutique. He’s sitting in the green room at one of Apple’s studios, in a part of Culver City, California, that you might call “industrial posh.” In another room, the producer A-Trak is putting together a mix for Diamond’s Beats 1 show, The Echo Chamber. It goes without saying that hardly anything Diamond does anymore is ignored, and that that has been the case for a very long time.

“Nobody at the record company wanted to have anything to do with us,” he continues. “So it gave us this total freedom and this vacuum in which we could create Check Your Head. If it were an anticipated record, they would’ve wanted to hear what [was] going on. But nobody was fucking paying attention, so we could do what we wanted.”

Even more than its audacious predecessor, Check Your Head presented an ambitious vision of a group who were still best known for a handful of novelty hits. Where Paul’s Boutique and, to a lesser extent, Licensed to Ill derived their thrills from the head-snapping sampling, they were both recognizable as hip-hop albums of their era; Ill is simpatico with contemporary records from the Beasties’ tourmates in Run-D.M.C., and Paul’s Boutique was released three months after De La Soul brought psychedelia to hip-hop with 3 Feet High and Rising (“Here we were trying to make something really creative and out-there, and we felt like, ‘Fuck, these guys beat us to it,’” Diamond says). Check Your Head, though, asks more of its listeners—a particularly bold move given that the band didn’t know whether they had any listeners left. It shoves muddy, overdriven hip-hop rapped through several layers of vocal distortion against hardcore pastiche and the kind of organ jazz you’d imagine hearing at someone’s lounge-age bachelor pad.

It’s not the most popular record in their catalog (Licensed to Ill still accounts for nearly half of their total sales), nor does it show them at the peak of their powers (that’d be its sister record, 1994’s Ill Communication, which delivers on Check Your Head’s stylistic promises while returning to the gang-shout jokiness of the first two albums). But that feverish pursuit of whatever sound Ad-Rock, MCA, and Mike D happened to be feeling—regardless of whether it fit the preconceived idea of who they were or what they could do as a band—as well as its budding sense of social consciousness make it the Beastie Boys album par excellence. Say the band’s name and the burst of allusions and associations that spill out like playing cards onto a tile floor all have their origins here.

With no tour scheduled after Paul’s Boutique, and feeling like they’d pushed sample-based hip-hop as far as they could take it, the Beasties didn’t have anything to do but bum around Los Angeles in vigorous pursuit of leisure. Horovitz picked up a few acting gigs, Yauch got into snowboarding and booked a trip to Nepal, Diamond helped to launch the X-Large streetwear brand. “Because of that failure, we had nothing but time on our hands,” he says. “Every single day, our ritual was to wake up, have coffee, eat breakfast, smoke pot, go record shopping, and get inspired.”

A normal day for most Angelenos, in other words, but it’s that last little action that separated them from their peers. The group was still reeling from the double-blow of 3 Feet High and Rising and Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (“We knew we’d never make something that good,” Diamond says of the latter). When A Tribe Called Quest released People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm in the spring of 1990, the Beasties recognized a kindred spirit in their leader. “We could see ourselves contextually fitting with [Q-Tip],” Diamond says. “We had a kinship with him and Biz Markie and Mike from the Jungle Brothers. We were all going out, digging for records, being inspired by some of the same stuff, and all wanting to push what people thought—and what we thought—hip-hop could be.”

“Every single day, our ritual was to wake up, have coffee, eat breakfast, smoke pot, go record shopping, and get inspired.” — Mike D

But to make a new kind of hip-hop record, they’d have to look beyond hip-hop itself. The Beasties had always had heterogeneous taste—they began life as a hardcore band, and the music critic Sasha Frere-Jones, who went to school with Diamond, remembers trying and failing to impress the young Beastie with his newfound knowledge of Isaac Hayes’s more obscure work—but the heady momentum of Licensed to Ill and all that followed had carried them away from their roots.

“There’s a weird thing that happened to some degree with Licensed to Ill. You come from hardcore and punk and this not-very-mainstream world where you print up some flyers and hopefully your friends show up and try to have fun,” Diamond says. “And then hip-hop was a bigger playing field, but it was still a very homemade culture. People weren’t trying to make records that sounded like hit records; the records were radical at the time.”

To reconnect with the humble radicalism that had provided their original guiding light, the band returned to the instruments they’d played when they were still a hardcore band goofing on other hardcore bands in the downtown scene. Horovitz played guitar, Yauch bass, and Diamond drums. And while they were still able to bash (“We felt like we had come full circle…[and] could embrace Black Flag and Minor Threat and Bad Brains,” Diamond says), they didn’t limit themselves to orthodoxy of any kind. Jamming first in Horovitz’s Hollywood apartment with producer Mario Caldato Jr. and keyboardist “Money” Mark Ramos-Nishita, and then at Cole Rehearsal Studios nearby, they’d run through funk workouts inspired by The J.B.’s, with Nishita’s versatile keyboard work rounding out and rooting their sound.

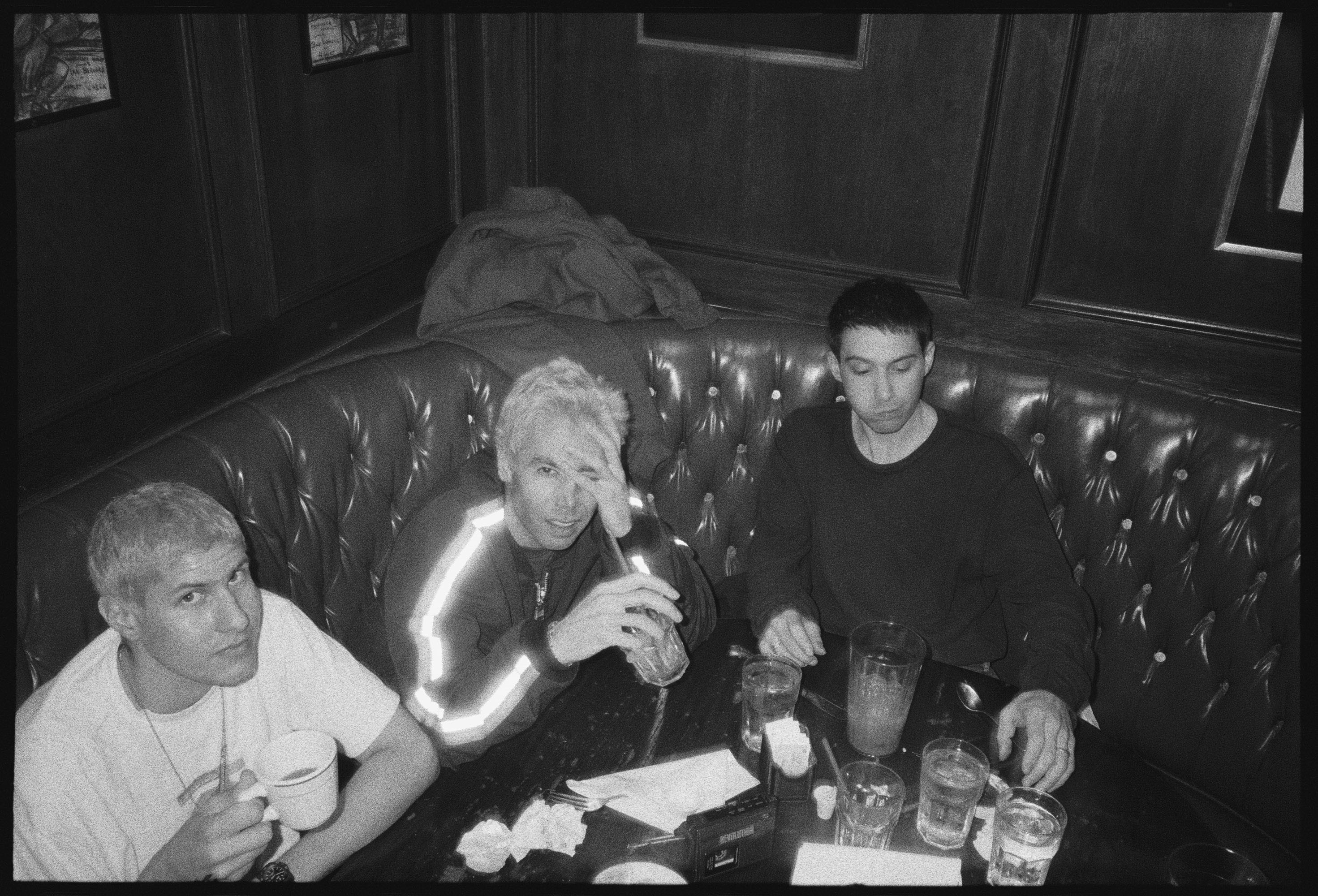

Money Mark, Mario C, and Mike D / photo courtesy of Mario Caldato Jr.

Caldato eventually noted that they could rent a space and build their own studio for a fraction of the cost of a professional room, so they found a rental in a former ballroom above a drugstore on Glendale Boulevard in the then-humble neighborhood of Atwater Village. Nishita, who was a carpenter by day, installed a basketball hoop and a half-pipe and occasionally slept in the space. Caldato filled it out with equipment. Outside, a sign proclaimed the name of a previous tenant—“GILSON”—but in a tidily poetic move the winds of change (or sheer entropy) had worn away the “IL.” G-Son Studios was born.

“We set everything up, and a lot of times we wouldn’t even make music,” Caldato says. The Brazilian-born producer had engineered Paul’s Boutique and would go on to co-produce Ill Communication and Hello Nasty after Check Your Head. Late-night sessions would be booked only to devolve into record-listening parties. “We were all [deep] into music, so everybody would go shopping individually and show [off] bags of records every night. We’d be playing basketball and listening to records by Sly Stone, James Brown, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry.”

It’s impossible to overstate the importance that those listening sessions had on the record and on the band. “We’d be listening to The Meters and then try to get up there to play like The Meters, and it would never sound like [them],” Caldato laughs.

“We came from hardcore! We didn’t come from conservancy, we didn’t go to music schools,” Diamond says. “So we can be totally inspired by [other artists] but we can’t in any way compete. [Instead,] we can just look at, like, what makes that work, why do we love it so much, what do we think is the coolest part? And then we’d try to make one bar that seems somehow cool to us in a similar way. In the process of doing that, it ends up being totally different.”

Still, it can be tempting to think of Check Your Head as a handful of big-beat hip-hop songs strung together by a series of genre exercises, and giving a song that sounds like an imitation of Richard “Groove” Holmes the name “Groove Holmes” doesn’t exactly dispel the criticism. If “Time for Livin’” comes across as a convincing take on early hardcore, that might be because its music was originally written by small-time punks Front Line (with lyrics ripped from Sly Stone, to boot). “Live at P.J.’s” name- checks Kool & the Gang in its title and Fugazi in the acute angle of Yauch’s bassline. “POW” sidesteps The Meters by swapping its titular bit of onomatopoeia for “Cissy Strut”’s “Hi-yah!”

"[Try] shit and be inventive and use the whole century as a palette." — Money Mark

But the album is guided by a kind of audacity that refuses to recognize itself as audacity. It doesn’t even dare you to suggest that following the sunbaked rock of “Gratitude” with a conga-led organ jammer is a bad idea; it succeeds almost entirely on the power of the Beastie Boys’ conviction that it would succeed, that the contours of their map might be recognizable even if the landmarks aren’t. “They could relate and dig deeper with Check Your Head, because it fit their [evolution] in a lot of ways, too,” Diamond says of the audience they discovered when they finally took the album out on tour. “It may not have been the same trajectory of music that they discovered along the way, but they could relate.”

It was “this freedom to [try] shit and be inventive and use the whole century as a palette,” as Nishita puts it. “Let’s just smash it all together.”

For all of the musical progressivism they demonstrated on Paul’s Boutique, the Beasties were far from sophisticated in their lyrical worldview at the time. Women are chased and left behind, and Yauch casually flashes his gun and—in a line that would quickly become infamous—tells a hater “I was making records when you were sucking your mother’s dick.” After all this time, it’s still shocking to hear that line coming from the same voice that would just a few years later pledge his “love and respect to the end” to all of the women in his life.

Licensed to Ill’s artistic merits are obscured by the immaturity that is occasionally the album’s motivating force, and the Beasties’ extended demonstration of their commitment to human rights both on- and off-stage (as well as Yauch’s hat-in-hand apology in Ill Communication’s “Sure Shot”) make the album something of an aberration within their catalog. Far from signalling a reinvention, the rhyming on Paul’s Boutique feels like the natural next step: the gang-shouting is more sophisticated and the references are more oblique, but they hadn’t yet realized that they might have something to say.

“It wasn’t until Check Your Head that we discovered ourselves and how our records affected people and how our actions affected people,” Diamond says. Later, while discussing the Check Your Head tour, he notes that it was the first time that they’d played rooms small enough to actually interact with the crowd in a meaningful way, and that they were no longer “these rock star people that needed to be separated from [the audience] anymore.”

A growing sense of responsibility might be why the group were hesitant to say much of anything at all on Check Your Head. Yauch at one point declared that it would be an instrumental album—an inspired idea, artistically speaking, that they would eventually realize on 2007’s The Mix-Up, but that almost certainly would’ve ended their career in 1992—and even when they relented, most of the vocals were delivered through “bullshit mics,” the rappers’ voices typically processed beyond recognition. Check Your Head is often at its most effective when saying least—see the narco-dub of “Something’s Got to Give,” one of the album’s conceptual high points that’s built around a wordless chant, Nishita’s wonky keyboard line, and Diamond’s dubby drumming. Caldato’s production takes cues from Lee “Scratch” Perry, but the lyric is decidedly of this world. “I wish for peace between the races,” the song’s opening lines go. “Someday, we shall all be one.”

"[Yauch] was an incredibly compassionate and empathetic human being. I don’t know why he had those qualities, but he had them in spades." — Mike D

Between sessions, Yauch took the aforementioned trip to Nepal. There, he was confronted with the effects of the Tibetan exile, which saw the Chinese forcefully removing Tibetans from their native land. “He was an incredibly compassionate and empathetic human being,” Diamond says of Yauch, who died of cancer in 2012. “I don’t know why he had those qualities, but he had them and embodied them in spades, and what he saw in Nepal deeply affected him. The concept that somebody who had certain ideological and philosophical beliefs that led them to get exiled from a country when they themselves were practicing nonviolence—it’s pretty hard to see the justice of it, obviously.”

When Yauch returned to G-Son, Diamond says, “It immediately shifted our awareness and our consciousness to a large degree, and that became a guiding—or changing—thing on the record.”

Diamond’s qualification seems apt. While the Ill Communication era would find them sampling the chants of Buddhist monks and Yauch co-founding the Milarepa Fund to benefit Tibetan independence, Check Your Head paints a portrait of a band in transition. The album-closing “Namasté” aside, it stakes its morality on a kind of non-sectarian sense of responsibility and happiness that takes as much from the noisy positivity of Bad Brains’ Positive Mental Attitude as it does Mahayana Buddhism.

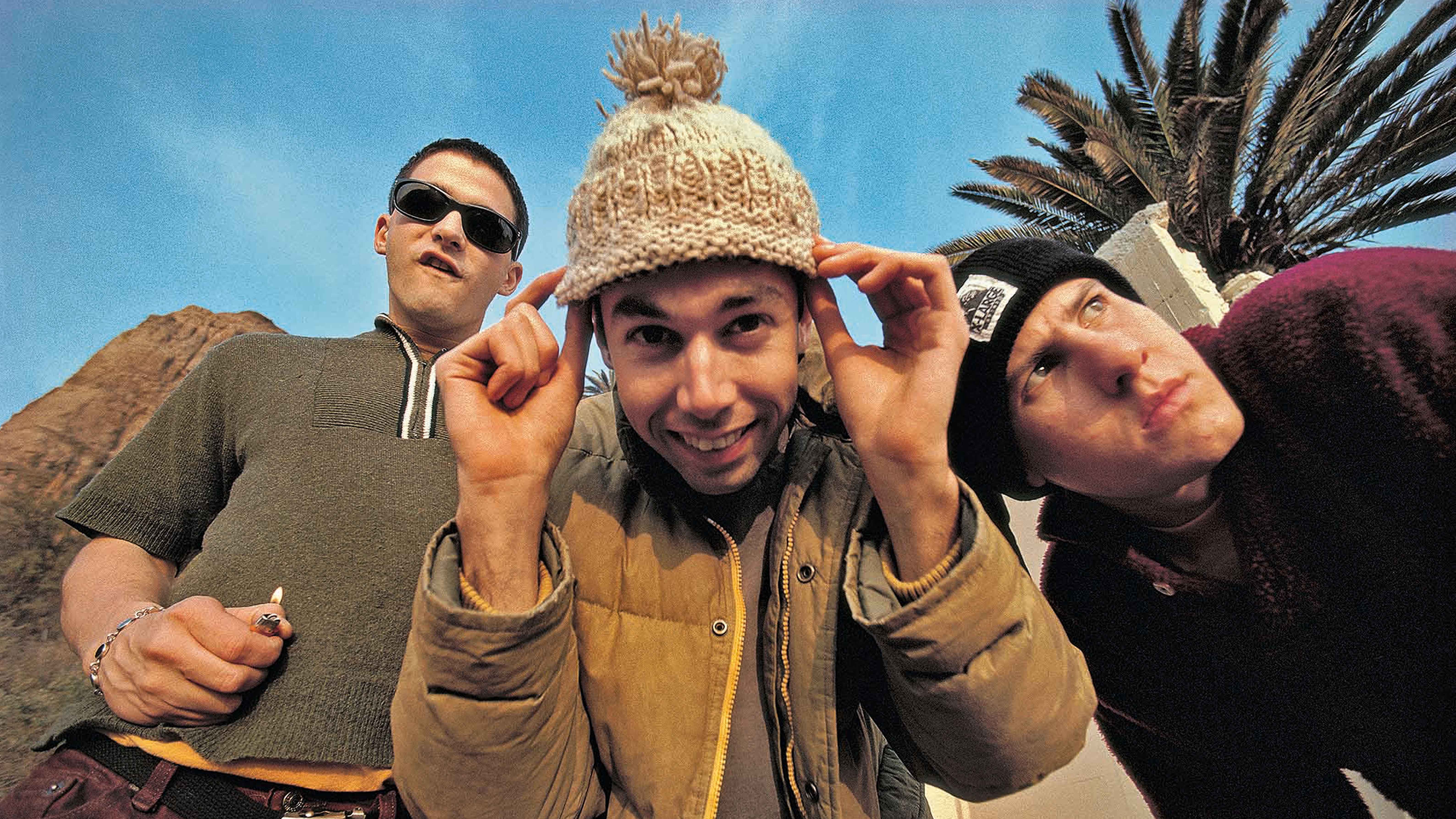

The Beastie Boys filming the “Pass the Mic” video / photo courtesy of Mario Caldato Jr.

Despite the lack of support and the chance that they might be working on the last major-label album of their careers, a comfortable and confrontational joy is the radiating spirit that guides Check Your Head. You can hear it in the way the sample of an evening spent enjoying expertly paired wines and chicken in “The Blue Nun” is followed by the yawking sax of Back Door’s “Slivadiv” in “Stand Together,” or in the goofy strut of “Funky Boss,” which sits right after “Jimmy James” near the beginning of the record, lest you should miss it as a statement of intent.

Even the big singles are powered by a straightforward positivity that must’ve seemed strange after the campy comedy of Paul’s Boutique’s disco-breakin’ “Hey Ladies.” They sound at ease in “Pass the Mic,” a posse cut in which they trade verses with a settled confidence; “to tell the truth, I am exactly what I want to be,” Diamond raps. Money Mark gooses a Southside Movement sample with a whorl of organ in “So What’cha Want,” the stomp of the song a redeemed echo of Licensed to Ill’s “Rhymin & Stealin.” “Gratitude” is rolled out with a straight face, as blunt a device as anything by the Beasties’ heroes in Fugazi. Yauch’s distorted bass and Horovitz’s stabs of guitar flash across one another like overlaid videos of lightning strikes. The music video presents them playing outdoors in the bright daylight of a quarry, the rim of a backwards Kangol keeping the hair out of Horovitz’s eyes as he rounds into the chorus: “When you’ve got so much to say, it’s called ‘gratitude,’” he shouts as a tracked camera rolls by. The fact that it’s all a direct rip of Pink Floyd’s Live at Pompeii film is the closest they come to winking.

Check Your Head was not a blockbuster—that would come two years later, when “Sabotage” pinned Ill Communication to the Billboard 200 for sixty-three weeks. But it did well enough to prove that there was a large, previously unknown audience who were willing to follow along with the Beastie Boys’ whims. The album’s polyglot approach would set the tone for both Grand Royal magazine and the band’s label of the same name, and the heavy-step beat of “So What’cha Want” made a home for itself on the nascent alt-rock radio. After the album’s release, they would invite Cypress Hill and the Rollins Band to open for them on tour, and the deeply Californian combination of stoney G-funk and brainy hard rock were a perfect complement to the aggressive charisma of the band’s live sound.

But perhaps more importantly, the album transformed Horovitz, Yauch, and Diamond from burnt-out novelties into career musicians for whom the development of taste and personal responsibility were of paramount importance. “The reason we were able to make that work for so long is because we did a pretty good job of being true to what felt important to us at a gut level,” Diamond says. “I feel like somehow we honored the inner compass and it worked.” A quarter century later, you can still feel what they’re feeling. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 6. You can download or purchase the magazine here.