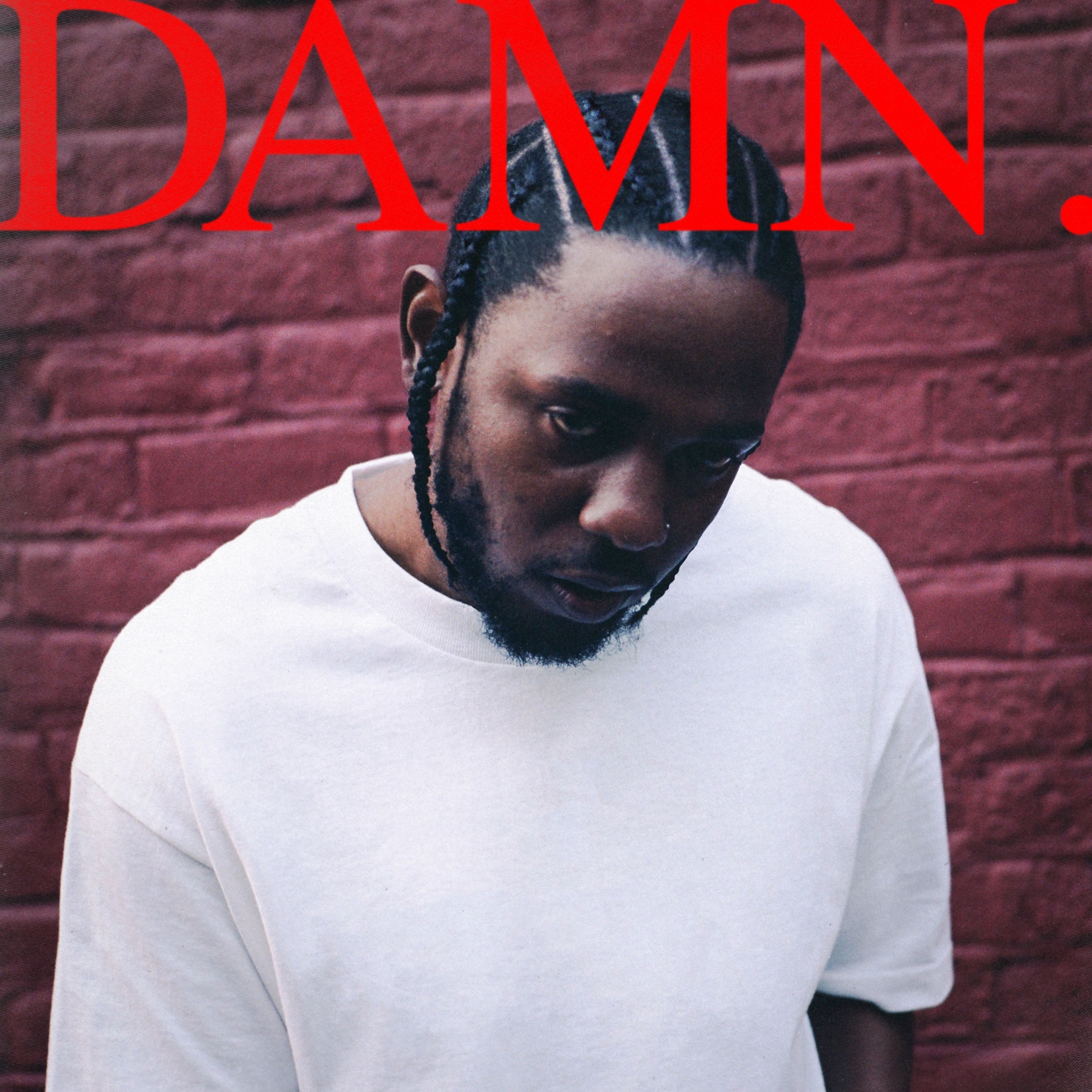

Kendrick Lamar

DAMN.

INTERSCOPE/TOP DAWG

9/10

Several of the song titles on Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. might have made for perfectly fitting album titles. This is a record about the warfare—spiritual, earthbound, internal—that’s always been brewing inside his own “DNA.,” about the things he carries in his “BLOOD.” It’s a record about the complicated makings of the man born “DUCKWORTH.” Every song title is a single word—there are also tracks called “LOYALTY.,” “LOVE.,” “LUST.,” and “GOD.,” for example—that suggest it’s about something elemental, some irreducible essence. The way each word slips into other songs, and the way key phrases are mixed within these disparate elements, hints that nothing’s quite so simple or straightforward, no matter how much the period in each title makes it out to be the final word on the subject.

Contradiction is nothing new for the rapper who was heralded from the beginning for his moral clarity, becoming a reluctant voice of the Black Lives Matter movement even as he declared himself “the biggest hypocrite of 2015.” So it makes sense that DAMN.—the most navel-gazing of all Kendrick Lamar records—would bear our struggle and triumph, swagger and fear, success and uncertainty, love and original sin. The cryptic album opener, “BLOOD.,” contains both an act of human charity and a startling moment of violence; if one of those impulses is more innately human than the other, Kendrick leaves it up to us to decide which one. And then on “DNA.,” legacies and lineages come together as the strands of his particular helix: “I got power, poison, pain, and joy inside my DNA / I got hustle, though, ambition, flow inside my DNA.”

Notice how nimbly he pivots from his internal monologuing—from his survey of dueling forces within his own soul—to that most vaunted and valuable of all hip-hop tropes—e.g., why he’s the dopest. He’s got the hustle and the flow inside him, while an unnamed adversary’s made of “sucker shit.” This is Kung Fu Kenny—who’s something of a new Kendrick persona, inspired in part by (no joke) Don Cheadle in Rush Hour 2—in pure shit-talking mode, and unlike on “King Kunta,” he’s not hiding behind a character. He falls back on familiar rapper tricks and techniques throughout the album, never with any sense that it’s anything but his own authentic self. To Pimp a Butterfly was a far-reaching, symphonic suite of black music past and present, and in many ways DAMN. follows suit—just in a different way. Rather than using jazz and funk as emotional signifiers, he tells his story through the kind of rapper’s delights that old heads will deeply appreciate.

There are no free-jazz breaks here, and no album-ending conversation with Tupac’s ghost. Instead, DAMN. is composed entirely of beats that feel hard-hitting, Spartan, stripped of excess. The thrills here don’t come from hearing Kamasi Washington wail on his sax, or from slinky G-funk grooves, but rather from the bars upon bars that Kendrick brings. With the notable exception of appearances from Rihanna, U2, and newcomer Zacari, he carries an almost-featureless album all on his own in masterfully structured rhetorical feats—not just the controlled chaos of “DNA.,” but the parallels and repetition of “FEEL.,” too. Throughout the record, he repeats his concern that nobody’s out there praying for him—a note of spiritual urgency that underpins everything here, suggesting that there’s a soul in the balance. There are also some rejoinders to Fox News talking heads, which are effective in providing the album a traditionalist’s sense of fight even if they also feel a bit beneath him. And what are we to make of the hype man who appears throughout the album, trying to get us amped for the new shit from Kung Fu Kenny? Is it well-earned triumphalism—or a sly parody of this “HUMBLE.” rapper’s inevitable turns toward bravado?

“I got dark, I got evil, that rot inside my DNA,” he tells us. He’s not the only one. Amid police sirens, he tells us on “XXX.” of how America doesn’t work for everyone, which segues into a song called “FEAR.,” where he confronts all the demons of his own insecurities, internal and external. One of the most successful recording artists in America wonders if his own well might run dry, here in the land of plenty—or if his better angels won’t be there to uphold his lofty reputation forever. He sings America; he contains multitudes. Then, at the end, he’s telling us his life story again on “DUCKWORTH.,” albeit in a different way than he did on good kid, m.A.A.d city. By now we shouldn’t be surprised that there’s nothing simple about it.