Alice Coltrane

Alice Coltrane

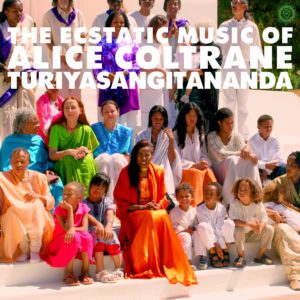

World Spirituality Classics 1: The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda [reissue]

JOWCOL/LUAKA BOP

8/10

It’s difficult to talk about the new collection of Alice Coltrane’s religious compositions without invoking tragedy. She was married to John for just four years before he died of cancer, after which time she became the disciple of Hindu guru Swami Satchidananda. Years later, it was the death of her son, John Jr., that led her to found the Sai Anantam Ashram just north of Los Angeles. It’s not unreasonable to assume that her spiritual questing was at least partly inspired by personal loss, and it’s that same sense of searching that animates these originally self-released recordings from the ’80s and ’90s—only what was born of pain is manifest here as something determined and joyful.

World Spirituality Classics 1 is autobiographical in other ways, too. Though these are Hindu songs of devotion, and they borrow heavily from Indian tonalities and structures—the album opens as though we’re just coming in on a song that’s been building steam for ages, and the whole thing has a swirling, trance-like quality to it—there are also elements of gospel music, which is where Coltrane got her start. In fact, some of the best moments on the whole set are the ones where everything fades away and leaves largely unaccompanied voices and hand percussion—rattling, jangling, keeping time for the congregational singing. For listeners who are more steeped in Christian than Hindu traditions, it may take a concentrated effort not to describe these sounds as Pentecostal, in their fervor if not in their form.

She pours herself into the music in other ways, too, actually singing lead on most of the songs—something that even fans and devotees may be surprised by. Her approach at the microphone is just as committed and physical as you’d think, and of course she brings an exquisitely bluesy touch to her work on the organ, occasionally punctuating it with sheets of noise from a synthesizer. There are also harps, of course—her main instrument—and always the voices. Always the tambourines and the shakers. Always the swirl of the mystic.

These songs were recorded to serve a practical religious function at the Ashram; they weren’t necessarily intended for public consumption, though most were recorded in a professional studio. Even so, they’re more about feel than they are the specificity of the religious content. These are songs that feel like they’re reaching for something; songs that sound like invocations. The intended audience may have been Hindu devotees, but the music speaks passionately and accessibly to anyone who still hasn’t found what they’re looking for.