It begins with John Keats. In a two-hundred-capacity venue—the Ivy Room, in Albany, California—Blake Schwarzenbach recites the first verse of “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by the English Romantic poet, and then something he said would never happen actually does. After a bit of stage banter, Schwarzenbach, Chris Bauermeister, and Adam Pfahler play together as Jawbreaker for the first time in twenty-one years.

They launch into “The Boat Dreams from the Hill,” the first cut from their third album, 1994’s 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, and any apprehension or anxiety about whether they’ve still got it melts into the sweaty throng of the crowd, into the room full of voices singing back at them, into the sheer disbelief that this is actually happening. The song—ostensibly about a dilapidated boat that will never see use again, but which really serves as a metaphor for the fragility of human dreams—rushes and roars, propelled by and fizzing with the raw, ragged energy that always defined the band, riding the tidal waves of expectation as if, indeed, there were none. This could be 1994. It’s as if they never went away.

The fact is, however, that the trio—who started life in New York in 1986 before making San Francisco’s Mission District their home—did break up. That show at the Ivy Room was one of a few very intimate warm-up gigs before the main event that’s brought them back together: a headlining slot at Chicago’s Riot Fest. If you watch Don’t Break Down, a recent documentary about Jawbreaker that gathered its members together for an awkward reunion of sorts in 2007, it becomes painfully apparent how big a deal this is on a personal level. The breakup was, indeed, more of a breakdown, and far from amicable.

But they didn’t just split up because of fraying tensions between members. The backlash of a punk community that abandoned Jawbreaker after it signed a major label deal with Geffen for fourth album Dear You also played a part. That record boasted a much crisper, cleaner sound than its three predecessors, which alienated the band’s core fan base even more and made them—literally—turn their backs on them.

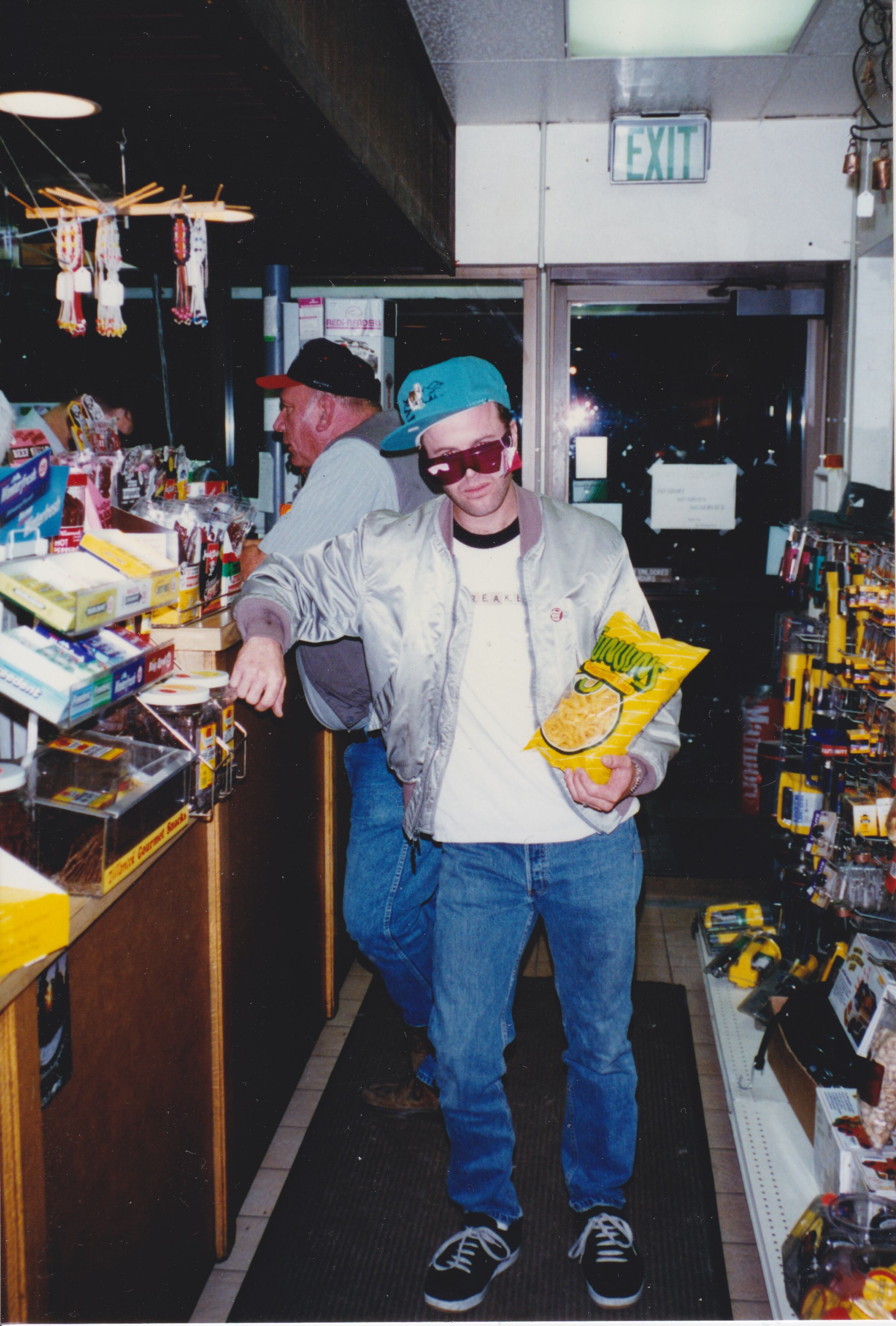

Jawbreaker in 1995 / photo by Don Lewis

That’s something Mark Kates, who signed Jawbreaker to Geffen, remembers well. “In the documentary, I tell a story about kids buying a ticket to see them at The Roxy and sitting on the floor with their backs to the stage when they played songs from the album—and then having to explain that to my boss,” he says.

“We felt we’d done the ultimate indie-to-major move with Sonic Youth,” he continues, “and there were no real political ramifications. We did it with Nirvana, we did it with Teenage Fanclub, we did it with a lot of artists. But there’s footage [from before the signing] of Blake saying into the microphone, ‘We’ll never sign to a major label.’”

While attitudes about selling out have shifted since then, in the two intervening decades, something else also happened. The band’s legacy didn’t just grow, but swelled significantly. They became more popular posthumously than they ever had been while active. Not only that, but their influence could be seen and heard in the burgeoning emo and punk scenes that Jawbreaker themselves had never quite fit into. Dear You—which, after moving only 40,000 copies, Geffen allowed to go out of print—became a coveted collector’s item. More importantly, opinion on that record started to evolve as people finally gave it the attention it deserved.

“I don’t really believe it was an ‘absence makes the heart grow fonder’ scenario,” says Brandon Reilly, who plays guitar for Long Island post-hardcore outfit The Movielife and fronts Nightmare of You. “I feel it was a textbook case of a band being so far ahead of their time sonically and lyrically with respect to the music scene they were a part of. Punk was traditionally straightforward and easy to grasp, and I think Jawbreaker was anything but that. Even in their moments of simplicity there was so much complexity.”

As accurate as that statement is, it’s also just the tip of the iceberg as to what made—and still makes—Jawbreaker special. It’s why they matter now, both inside and outside of the punk community. It’s why, for the past decade or so, festivals have been offering them obscene amounts of money to reunite.

“Even in their moments of simplicity there was so much complexity.” — Brandon Reilly

“Over the years, I would hear rumors about the offers they were getting,” says Sergie Loobkoff, guitarist of Samiam, a Berkeley punk band who had a very close relationship with Jawbreaker back in the day. “And even if they’re exaggerated rumors, it was still quite a lot of money. Someone in the music industry told me they got an offer in the million dollar range just to do a tour of all the House of Blues venues. Who wouldn’t do that, and why wouldn’t you do that? Unless you happen to be rich—and I know from Adam that he’s definitely not rich, and I happen to know that Blake was a bartender for a time. I was like, ‘Whoa! Why wouldn’t he do that?!’ And part of me admired that, because he was really sticking to his guns and he had such an opinion of what was right for him and for Jawbreaker. But another part of me was like, ‘You fucking idiot!’”

In the end, it was an offer from Riot Fest that finally convinced Schwarzenbach. His resistance and hostility toward reviving Jawbreaker’s body had finally gone. Although they aren’t doing interviews, the singer did appear on the pilot episode of the Missing Words podcast, where he revealed what it took for the reunion to happen.

Blake Schwarzenbach

“I actually had nowhere else to go,” he told host Matt Pullman. “It just happened at a moment. What it took, honestly, was a good offer from an interesting big fest. Riot Fest feels like one of the few guitar-based, kind of punk-based stage events going on. [They] appealed way more than some of the others that had been asking us.”

Despite heading up two critically acclaimed bands post-Jawbreaker—Jets to Brazil and Forgetters—as well as teaching undergraduates while studying British Romanticism at New York’s Hunter College (hence the Keats recital), Schwarzenbach saw every other road close off for him.

“My life was just stopped completely,” he explained to Pullman. “I don’t think I am coming to it from hunger. It was just this huge thing that was sitting right in front of me the whole time. I kind of hit a moment where I was like, I can either apply for a hundred jobs and not get them—I mean, dog walking, I couldn’t get hired. Adam wrote as he does every year and goes, ‘I just gotta tell you what’s being offered right now.’ [From there] it was just a matter of feeling the other guys out and then seeing that everyone wanted to do it, and making a plan to meet up. We didn’t agree until we practiced and thought that this actually sounds like us enough that we can pursue it.”

Chris Bauermeister

Hyper-personal yet fully universal, Jawbreaker’s songs tap into a world that most of us experience but are unable to describe. It’s a world of monochrome, film noir darkness, late night cigarettes, and a poetic romanticism that elevates the catalog way above what most other bands—let alone punk bands—are capable of. The unrefined brashness of earlier cuts might make them seem grating to the unfamiliar ear, but spend time listening to their music while reading along to the lyrics—“West Bay Invitational,” “Chesterfield King,” “Sea Foam Green,” “Condition Oakland,” “Kiss the Bottle,” “Ashtray Monument,” and “Ache” are all good cases in point, to name a few—and a whole new world opens up. To quote “Condition Oakland”: “Read and I felt so small / Some words keep speaking when you close the book / Drank and just about smiled / Then I remembered us in that bed.” Those four lines combine existential crisis, the insignificance of humanity, the burden of wasted potential, literature, alcohol, nostalgia, and sex, plus that deep, unspoken longing and hunger to strive for greatness—or at least to do more than just exist—that resides within us all.

“Lyrically and musically, no one was doing what Blake was doing with Jawbreaker,” says Reilly. “It was so rich, complex, melancholy, and bittersweet. The lyrics were more like prose. They told a three-dimensional story, and he wasn’t afraid to feel and be vulnerable in a rugged scene. His chords were barely ever straightforward; there was always an extra note thrown in that took the chord and feeling to a way more emotional, grander, and regal place.”

Adam Pfahler

It’s not just about Schwarzenbach, however, but the effect of what happened when all three of them played together.

“A lot of people will talk about Blake,” says Dave Hawkins, who played in Engine 88—another of Jawbreaker’s contemporaries—and who co-runs the Lost Weekend video store in San Francisco with Pfahler, “because he’s an absolutely amazing songwriter, but I want to give love to the [rhythm section], too, because what grabbed my attention first was Adam and Chris’s playing on 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, and the driving nature of the music. And it still really stands out to me.”

All of which is to say that Jawbreaker isn’t just another band, and their songs are so much more than just songs. Rather, the trio somehow manage to reveal, through the combination of their music and their words, a rare truth about the human condition that few—if any—songwriters come close to matching. To do that in one song is something most artists only ever dream of doing. Jawbreaker do it in most. Hopefully, now, the rest of the world can discover that, too—albeit twenty-five years late. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 7. You can download or purchase the magazine here.