When last we encountered Nasir Bin Olu Dara Jones on a full-length, critics and fans alike fell for 2012’s Life Is Good, a Here, My Dear pastiche obliquely analyzing his divorce from pop star Kelis. Finally, listeners gushed, a rapper aging gracefully, one vulnerable and honest enough to admit his shortcomings and insecurities on record! Six summers, a few Illmatic anniversary galas, and one unfulfilled album promise later, Nas’s return was announced last April as the third in a series of seven-track projects produced by a suddenly ignominious Kanye West. And if his association with a Trump-apologizing, slavery-doubting “free thinker” wasn’t enough to unravel an album rollout, the announcement was followed by Kelis’s allegations of domestic violence over the course of the couple’s five-year marriage—accounts which squared with earlier claims of abuse by Carmen Bryan, the mother of Nas’s daughter.

The newly surfaced abuse allegations were disorienting not because Nas was ever hip-hop’s conscience—even in his best moments, he was too self-indulgent for that title—but because he was a consistently empathetic witness, his ability to understand and inhabit his flawed subjects in quick glances a defining trait of his character studies. In 2001’s “2nd Childhood,” a wayward ex-con “moves with his peers, different blocks, different years, sitting on different benches like it’s musical chairs”; 2004’s “Reason” paints a broken family: “I could imagine them asking, ‘What type of human being / Could leave his family, go back to the Caribbean?’” Was the moral compass promulgated by the rapper who famously took Kobe Bryant to task on behalf of black celebrities just another fictive device?

Under any circumstance, criticism of Nas’s music is rather precarious: his incisive narratives inspire a fierce, Springsteen-esque devotion among fans, meaning that reviews tend to read as either overly invested or distantly clinical. Depending on one’s perspective, he’s either among the finest chroniclers and technicians in rap history or a whipping boy for an overrated aesthetic and epoch of East Coast hip-hop, with little ground in between. And yet, each instance of bewildering concept records, poorly selected producers and collaborators, and queasy sex raps at odds with his literary compassion has cemented his status as rap’s tragic hero, a prodigy with all the promise and talent in the world, who too often falls victim to his own poor judgment. If his inability to surpass his 1994 debut Illmatic has become his cross to bear, he seemed all the more human for it.

As beloved icons respectively disgraced by their questionable judgment, Nas and Kanye comprise something of a match made in hell in 2018. Nasir’s scattershot twenty-six minutes are plagued by empty sanctimony and off-putting content, the faux-wokeness of two forty-something “free thinkers” retconned as renegade advocacy. Take the opener “Not for Radio,” which, in a nod to Nas’s 1999 collaboration with Puff Daddy “Hate Me Now,” features an animated Diddy excoriating Nas’s critics. Where “Hate Me Now” focused on society’s distaste for two self-made African-American millionaires from New York City’s roughest neighborhoods, the vitriol of “Not for Radio” augurs something much darker. “Fox News was started by a black dude,” Nas equivocates in a typical spate of galaxy brain.

Nasir’s scattershot twenty-six minutes are plagued by empty sanctimony and off-putting content, the faux-wokeness of two forty-something “free thinkers” retconned as renegade advocacy.

Nasir is rife with anti-media sentiment and fake news finger-pointing. This is most evident on the album’s linchpin “everything,” an epic eight-minute suite with a stunning a cappella intro. “This is your court, there are no laws,” Kanye and The-Dream harmonize before Nas clocks in, “When the media slings mud, we use it to build huts.” If Nas’s second verse isn’t an anti-vaxxer screed, it sure as heck sounds like one (“Why’d you let them inject me? Who’s gonna know how these side effects is gonna affect me?”), a conspiracy he’s nodded to in past music.

On a technical level, Nas’s vocals are confounding; he seems capable only of a single clipped, barked delivery. The result is something like a poetry slam someone tried turning into a symphony by adding layers of choirs and continental jazz, and notably poor mixing adds to the sense of haphazardness. Nas’s writing is ceremonial in flavor, but lacks the narrative arcs and dramatic reveals he perfected as a veteran rapper, echoing like scribbled essay drafts and diary entries. “White Label” and “Bonjour” are inoffensive and inconsequential, champagne toasts wanting for a commemoration.

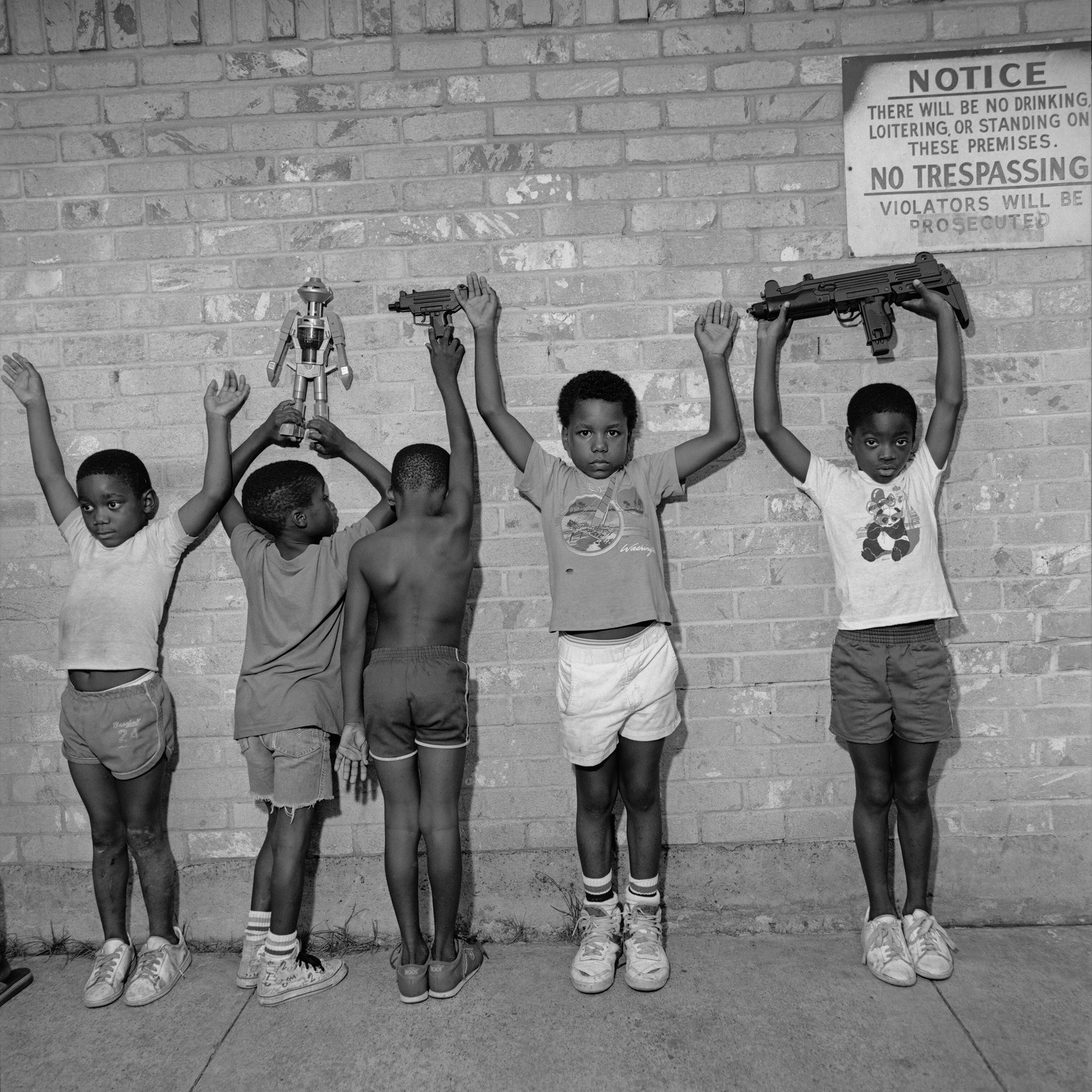

Nasir’s best moments are mixed bags. The Slick Rick–sampling “Cops Shot the Kid” is largely meaningless, Kanye halfheartedly playing both sides of a one-sided debate. “Adam and Eve” has a noirish, Godfather-esque instrumental, so of course Nas raps about Fredo Corleone and rigatoni. The finale, “Simple Things,” comes closest to recapturing the wistful nostalgia of 2004’s Street’s Disciple and 2006’s Hip Hop Is Dead, referencing Nas’s brother and children—but at only two minutes it’s a tease.

As disappointing a record as it is, Nasir is a truly fascinating artifact, a collision course of pariahs, the album 2018 deserves. Nas’s decades-old construct of an endearingly flawed genius has been all but rendered invalid, leaving listeners with a baffling, tossed-off set of defensive sketches.

In the vocal intro to his most iconic single, 1996’s “If I Ruled the World (Imagine That),” twenty-two-year-old Nas theatrically posed an existential question. “Life,” he mused. “I wonder…Will it take me under? I don’t know.” Somehow he failed to account for the possibility that he’d take his own damn self under. FL