John Carpenter has an Oscar, but he doesn’t know where it is. The award was won for The Resurrection of Broncho Billy, a 1970 short film he worked on with a handful of other University of Southern California students, and it was subsequently kept by the school on behalf of the filmmakers. (“The head of the USC cinema department brought the Oscar in a paper bag and showed it to us,” Carpenter told USA Today a few years ago. “That’s the height of arriving in Hollywood.”) Carpenter cowrote, edited, and scored the short, which is about a college-age kid stuck in the bustle of a big city despite being obsessed with cowboy movies and the Old West. The character is endearing but ultimately somewhat tragic; the city chews him up and spits him back out.

Oscar in a university drawer somewhere, Carpenter set off on a bullheaded-yet-elegant career in which he became known for doing damn near everything himself (he is quite literally the most noteworthy director/composer alive)—and, while we’re talking about it, he’s made his own fair share of odes to Westerns, too. His traditional feature debut, 1976’s Assault on Precinct 13, is a reimagining of sorts of Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo, but set in the sketchy depths of gang-torn LA, and incorporated with elements of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. Cowboys and zombies, Westerns and horror.

The film was made on a shoestring $100,000 budget—independent by independent standards—and did poorly at first, but it slowly built acclaim, eventually making a splash at Cannes in 1977. Soon after, a man from Miracle Films purchased Precinct 13’s theatrical distribution rights for the United Kingdom. His name was Michael Myers.

“I believe in evil, sure,” Carpenter says, sitting in the living room of a pleasant Hollywood home that he’s converted into an office. “It exists, it’s in nature, it’s in humans. I don’t believe in the supernatural, but that’s just a belief. I could be convinced otherwise if a flying saucer lands out there.”

He’s talking about Halloween—and, in this case, specifically about the composition of Michael Myers, a character who has seeped into the framework of our culture as much as any in film history, for better or worse, depending on whom you ask. Myers, like the shark in Jaws or Regan in The Exorcist, has fundamentally changed the landscape of people’s fears and neuroses. For forty years now, the image of a jumpsuit-clad man in a disfigured Captain Kirk mask, spray-painted white, has lingered in the peripheral darkness of our kitchens and laundry rooms. Carpenter’s depiction of an escaped mental patient’s massacre of three high school students in the fictional town of Haddonfield, Illinois, on Halloween night in 1978, has scared viewers out of ever watching horror movies again.

“He’s not quite a human,” Carpenter explains. “Not quite. There’s something scarier to me about that. ‘I’m not sure what this thing is that’s after me. Is it a man? What is he?’ That was my idea.”

Halloween has come to define Carpenter’s career, despite the fact that none of the cult-hero director’s later films are anything like it, really—and despite the fact that many of those later films are true landmarks in their own right. Even with the legacy of midnight-movie sci-fi classics like The Thing and They Live looming large, he can’t escape Halloween, which lingers in his shadow in the same way that Myers does behind innocent Laurie Strode as she walks home from school. Even indirectly, the film is always there: That office in Hollywood? It’s not too far from the actual house that served as Laurie’s in the original film. (“Total coincidence,” he says, as if the proximity had never even occurred to him.)

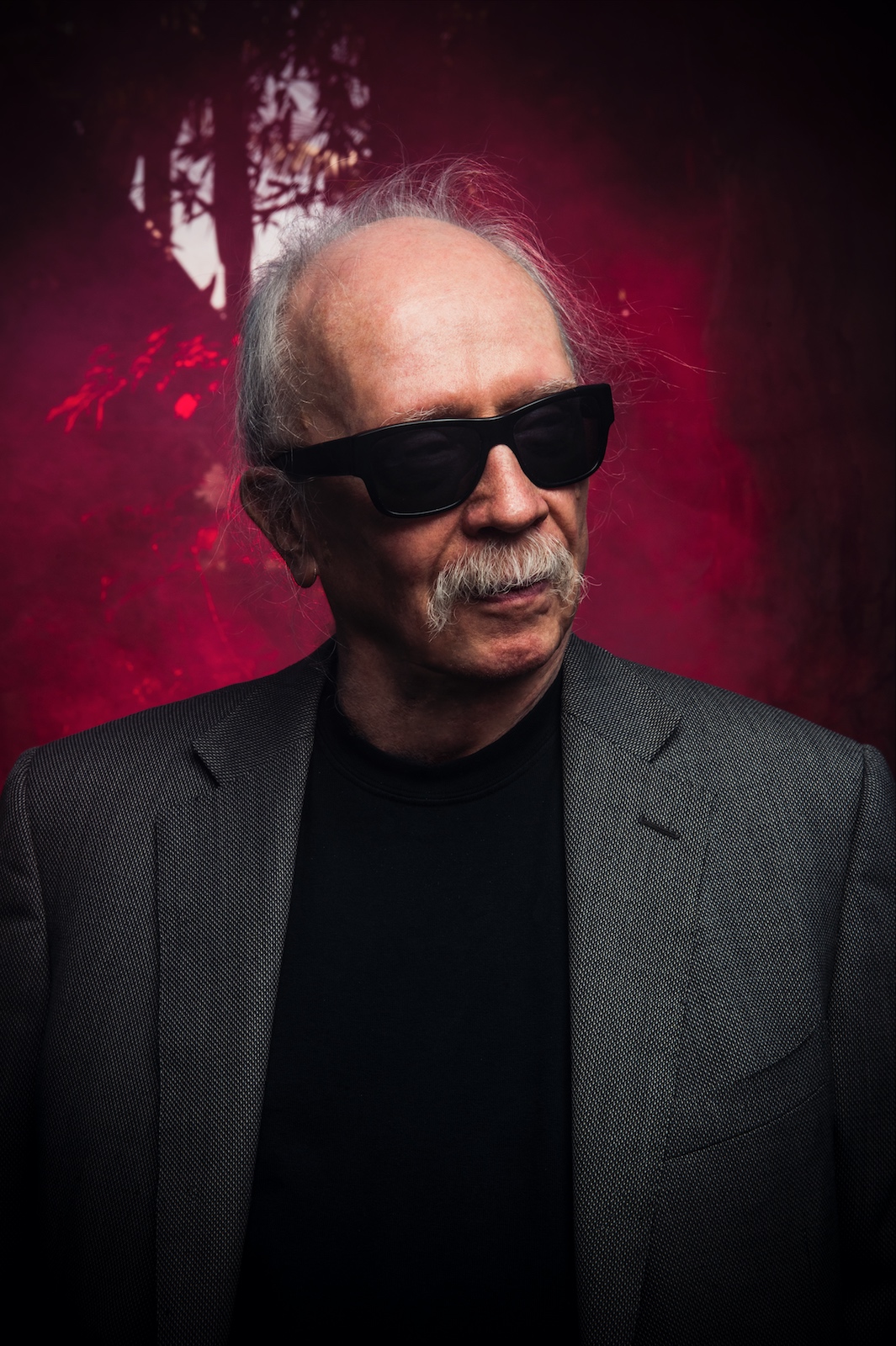

Surrounded by props and posters from his various films, Carpenter sits down in his leather chair of choice to discuss past and future. Maintaining a stern mustache and a casual ponytail, he is both an intimidating and welcoming figure, speaking with unquestionable conviction one minute, joking around like there’s nothing to have conviction about the next. In his speech, he occasionally adopts a well-practiced, half-sarcastic ~spooo0ky~ voice, and over the course of an hour-long conversation, he drops at least several “hell yeah”s.

Carpenter, now seventy years old, is turning and facing his shadow on the record because there’s a new Halloween in the world. It’s the eleventh film in the series, but for the first time since 1982’s Halloween III: Season of the Witch—a Carpenter-produced (failed) attempt at expanding the franchise outside of the realm of Michael Myers—he was actually involved in this one’s making, executive producing in addition to recording a reprisal of his iconic original score. The 2018 Halloween, directed by David Gordon Green, who wrote it with Danny McBride and Vice Principals collaborator Jeff Fradley, ignores all of the previous nine sequels, simply picking up the story straight from the original, four decades later.

“Jason Blum [of Blumhouse Productions, the studio behind the film] said, ‘You know, instead of just sitting on the sideline and saying you don’t like these sequels, why don’t you come and help this time? Actually contribute, bigmouth,’” laughs Carpenter. “I thought, ‘OK, I could do that. I could shepherd it through.’”

John Carpenter was born in Carthage, New York, but his family moved to Bowling Green, Kentucky, when he was about five, after his father, a music professor, took a job at Western Kentucky University. Young John did not like it there.

“My parents were Yankees, and we all moved down to the South,” he remembers. “And this was the Jim Crow South. It was not a very pleasant place in those days, and I was a fish out of water. I was not a hillbilly—I was not one of those country boys—so they loved to pick on me. And that was not fun. I learned all about evil in that little town when I was growing up.”

“[Michael Myers is] not quite a human. Not quite. There’s something scarier to me about that.” — John Carpenter

Going to the movies was an escape for John—as was making them, eventually. He got out of Bowling Green to go to film school at USC in Los Angeles, where he was initially so naïve to the sprawl of the city that he tried to walk from the airport to campus, luggage in hand. (That’s a cool ten-mile hike, if you’re wondering—and not a welcoming one, either.) “I looked at a map, and it looked like SC was right up the street,” he laughs. “So I just started walking. I got out of the airport—I think I made it down to Manchester [Avenue, near Inglewood], and started up the street and thought, ‘You know, this is not a good thing.’ So I took a bus.”

Carpenter dropped out before graduating, but first he made a key friendship with Nick Castle, a fellow USC student. Castle was the cinematographer on Broncho Billy (he also doesn’t know where the hell that Oscar is), and played the mischievous, orb-like alien in Dark Star, a school-produced comedic sci-fi short-turned-feature that was directed, cowritten, and scored by Carpenter. (The other cowriter of Dark Star was Dan O’Bannon, who went on to write Alien a few years later. Castle later became a notable filmmaker as well; he cowrote Escape from New York with Carpenter in 1981 and directed the Walter Matthau–led version of Dennis the Menace in 1993.)

After Precinct 13’s relative success, a pitch came in from the film’s distributor, Irwin Yablans, who wanted Carpenter to make a movie called The Babysitter Murders—about, well, babysitters getting murdered and stuff. B-movie fun. Carpenter agreed on the condition of final cut—he wasn’t going to let the project be contained as a straightforward thriller, like his as-yet-unaired TV movie Someone’s Watching Me! was on its way to being—and he wanted his name above the title. “I saw this as a showcase movie,” he says. “I approached it that way.”

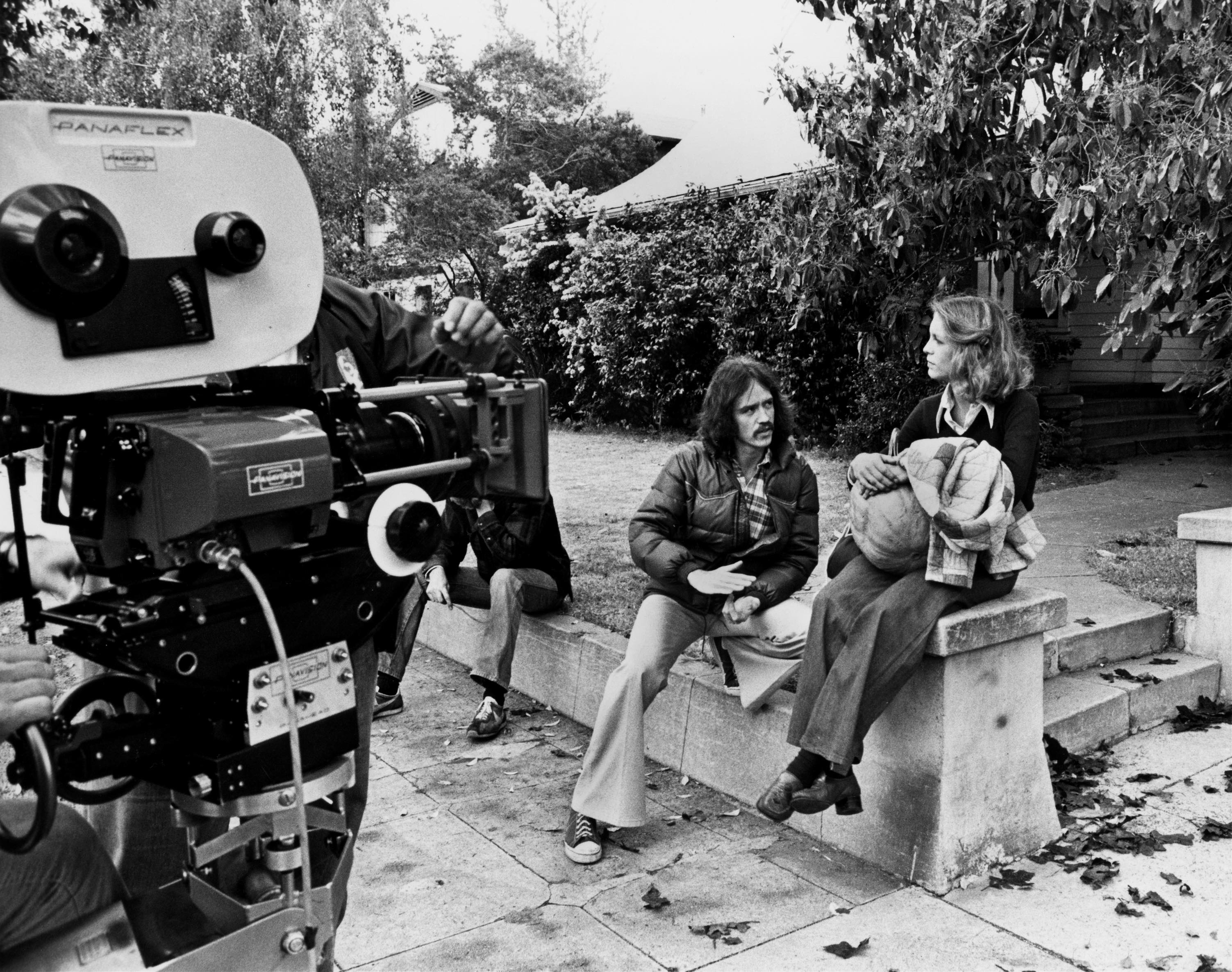

With a paltry budget of $300,000 secured (financier Moustapha Akkad had been making a movie that cost $300,000 a day, so the project seemed like a throwaway gamble of sorts), Carpenter got to work, enlisting his then-girlfriend Debra Hill, who was the assistant editor and script supervisor on Precinct 13, to be the sole producer and cowriter on the film with him. (Hill later cowrote The Fog with Carpenter in 1980 and Escape from L.A. with Carpenter and Kurt Russell in 1996. In 2005, she passed away from cancer.) The lore goes that Yablans was the one who eventually suggested the setting and name of “Halloween,” although Carpenter is wary of how much credit he deserves. “He had nothing to do with it creatively,” Carpenter says, seemingly still kind of pissed off about the way the story is generally spun. “Irwin is a pirate. Be careful of what you believe.”

Hill and Carpenter made their first big decision by casting nineteen-year-old Jamie Lee Curtis as the lead, Laurie, in what would serve as her big-screen debut. It was Hill, a savvy marketer as well as filmmaker, who in particular grasped onto the kitsch value of having the daughter of Janet Leigh—best known for taking a very unfortunate shower in Psycho—as the star of the movie. The most expensive casting decision (costing the production an extra $25,000) was hiring Donald Pleasence to play Dr. Sam Loomis, Myers’ psych-ward doctor who is frantically trying to track his patient down before the inevitable happens. (“Sam Loomis,” by the way, is a reference to the Psycho character of the same name.) But as for casting the character of Myers himself? You know, the guy who’s on-screen almost the entire movie? That wasn’t so planned out.

“I knew John was doing a new movie,” Nick Castle remembers over the phone, “and I found out that they were in pre-production close to where I lived. So I went down and said, ‘Can I just hang and watch the whole thing? Because that would be really helpful for me—I want to be a director, you know.’ And John said, ‘OK, why don’t you be the guy walking around with the mask on,’ and I went, ‘Uh, OK.’” He laughs here, still amused by the ridiculousness of this story. “That’s as simple as it was. It was offhanded, one pal to another. I think John has embellished it to be, like, he knew the way I walked and stuff like that.”

This is true. When asked, Carpenter dismisses Castle’s humble portrayal of how he got the role of “The Shape,” as it is curiously but tellingly billed, and instead insists that it was a deliberate choice, citing his friend’s gracefulness and tact. (“Nobody walks like he does,” Carpenter says. “Nobody.”) But regardless of whose version of the story you believe, there is validity to Carpenter’s explanation: Castle’s performance is nuanced in its own way. Myers glides across the screen in a manner that makes the scenes surrounding the murders just as scary, if not more so, than the actual murder scenes themselves.

Consider the definitive moment of Castle’s performance, which occurs after Michael has pinned the unlucky Bob—who really shouldn’t have said “I’ll be right back” to the soon-to-be-unlucky Lynda before heading downstairs—to the kitchen wall with a frickin’ butcher knife. Instead of heading straight to Lynda, Michael instead pauses and simply stares at Bob, gently turning his head ever so slightly, back and forth, observing the body like a dog might observe a tree. It’s a subtle and somewhat inconsequential moment, but it gets under your skin.

“That’s the perfect kind of acting for me: Put a mask on and tell me where to go and tilt my head and stuff—I’m perfect when I can do something that simple. Believe me: [playing Myers] took absolutely no talent.” — Nick Castle

“That’s the perfect kind of acting for me,” Castle explains, noting that he actually suffers from stage fright, dating back to a bad experience with a Shakespeare soliloquy in college. “Put a mask on and walk me around and tell me where to go and tilt my head and stuff—I’m perfect when I can do something that simple. Believe me: [playing Myers] took absolutely no talent,” he laughs. Talent or not, Carpenter got his money’s worth from his old friend: Castle was paid twenty-five dollars a day.

Production of the film blazed by in a month’s time, crewmembers fielding numerous roles, pennies pinched every step of the way. The set-design team, for example, who were faced with the challenge of making Southern California in spring look like fall in Illinois, had to gather their prop leaves after each scene to reuse them for future shots. (“I couldn’t hide all the palm trees,” Carpenter bemoans of shooting in LA. “I couldn’t do it.”) Also worth pointing out: A popular behind-the-scenes photo from the shoot shows Castle drinking a Dr. Pepper through the Myers mask, but the whole reason the photo even exists is because, desperate for something to spice up the craft services department on set, the production struck a deal with Dr. Pepper to donate sodas under the condition that the cast and crew be photographed drinking them.

Carpenter refers to Halloween as a “word-of-mouth movie,” its popularity spreading in the weeks after its release like a dare from friend group to friend group. Reviews initially weren’t strong, but a glowing late review from Tom Allen in the Village Voice started to turn the tide. “It became a bigger thing than it was,” Carpenter notes, blasé. “Roger Ebert interviewed me—he liked it. Nice guy.”

Back before production had begun, Carpenter worked it out with Akkad that he would be paid only $10,000 to make the film, with the tradeoff being that he receive 10 percent of the movie’s profit. Halloween made $70 million worldwide.

Because it became culturally ingrained so quickly, the perception and legacy of Halloween is easy to misinterpret. It ushered in a so-called “golden era” of the slasher film, yes, but the work of that era quickly disintegrated into trope-filled monotony—and most of the genre’s modern interpretations are viewed as something of a guilty pleasure. (Nobody is embarrassed to suggest watching the original Halloween to their friends, but if you want to ask someone to watch the new one, you might be tempted to qualify that ask with an “lol.”) Slasher films skyrocketed in number after 1978, but even so, the genre never came close to reaching the critical and artistic heights that Carpenter took it to with a few weeks of work and a few cases of Dr. Pepper. Appropriately enough, Carpenter’s exploitation movie begot a different type of exploitation: the exploitation of itself. An entire industry inevitably fed off of what was, at its core, a simple, crass exercise by a filmmaker challenged with a specific assignment—a filmmaker who was evidently uninterested in further pursuing the dead-end streets that the assignment sent him to explore in the first place. (Carpenter’s next directing project after Halloween was a TV movie about...Elvis.)

There’s a crucial irony at the center of the proliferation of Halloween-inspired mediocre-to-bad slasher films in the ’80s and ’90s, which is that Carpenter himself has adamantly rejected, numerous times over the years, the central—and at this point, definitive—trope of “the people who have sex get killed and the virgin survives.” This plot device was so abused that it was eventually easily satirized by a key offender himself, Wes Craven, with Scream in 1996—and even after Carpenter repeatedly told everyone that they were projecting some messed-up version of their own Catholic guilt onto his movie’s symbolism, the sex-before-death approach continued on even within the universe of later Halloween films. The promiscuity, along with a subsequent punishment for that promiscuity, wasn’t a remotely important element of the movie to Carpenter, but for one reason or another, it became important to us. It was what we wanted to see.

“All I can say about the Myers-only-kills-the-girls-who-have-sex issue,” Carpenter says in Gilles Boulenger’s book The Prince of Darkness, “is that the story starts out with a little boy seeing his sister fucking her boyfriend upstairs and killing her for it. So it seems to me that part of what he’s doing is getting vengeance on her because of an Oedipal or incestual thing. Also, if the girls are not so ‘sweetie pie,’ it adds a kind of an odd element when you are watching the movie.” The interview transcription notes that Carpenter smiles mischievously here. “Nobody will believe this. Nobody believes me.”

OK, so if you’re willing to listen to the guy who made it, Halloween definitely isn’t about morality or sexuality—but what it is about has proven harder to pin down. When presented with the suggestion that the collective societal anxiety over home invasions following the Manson Family murders might have played into a story about innocent people getting killed in their bedrooms while they sleep (or do other stuff), Carpenter offers a slightly different interpretation: “Don’t think of it as a home-invasion movie,” he says. “Think of it as a siege movie. That’s something I’ve been obsessed with since I was young. A great example of a siege movie is Zulu: A hundred and fifty British officers fight four thousand Zulu warriors as they’re trapped in this little place—and I think that’s probably what I felt like in Bowling Green. I was trapped by that Jim Crow outside—it was coming to get me. The big country boys were going to come in and beat the hell out of me. Assault on Precinct 13 was definitely a siege movie. So Halloween probably was in a way, too. I mean, [Myers] was after the girls and such.”

Either way, one takeaway remains: Don’t forget to lock your doors.

These days, from the safety of his home, Carpenter is working on developing a few TV productions—and he recently helped pen a series of Big Trouble in Little China comic books—but he seems to spend most of his time focusing on music. Working with Cody Carpenter, his son, and Daniel Davies, son of Dave Davies of The Kinks, Carpenter has put out three synth-drenched records in the past few years on the indie label Sacred Bones. He tours a bit, too: For the second year in a row, John, Cody, and Daniel will be playing at The Palladium in Hollywood on Halloween night.

“Movies are rough shit, man,” Carpenter explains. “Music is a joy—it’s a joy to do.”

This partially explains Carpenter’s return to the Halloween series, in which he took advantage of a higher budget and better technology to rerecord the spine-tingling 5/4 theme. (And maybe that means the Academy will use the opportunity to replace the Oscar that USC has hidden away somewhere; in his entire career, Carpenter has yet to receive a formal nomination.) Castle, too, is back for the 2018 film: Most of the new Myers performance was done by James Jude Courtney, but for the scene in which Laurie—once again played by Jamie Lee Curtis—and Michael first see each other again, that’s Nick behind the suit. He “can’t retire on it,” but they paid him more than twenty-five dollars a day this time.

Carpenter doesn’t like to rewatch the original Halloween—or any of his old movies, for that matter—but he’s in small company on that front, as the movie seems to get a theatrical rerelease year after year (this year, a remastered 4K cut is being shown across the country), and not a single person seems to come away from one of those screenings with the conviction that the movie didn’t scare them this time. It’s the little details and offhand images that continue to land the hardest: a handful of hospital-gown-wearing psych patients wandering around at night, in the rain; Michael standing in a doorway, wearing a sheet over his head, just breathing; Laurie frantically banging on a neighbor’s front door, screaming for help, only to have the porch light turned out on her. Several generations on, John Carpenter’s ninety-minute suburban fever dream is still the quintessential American horror experience.

“‘There but for the grace of God go I’—that’s what you’re saying to yourself,” Carpenter considers, on the topic of why we so badly want to be scared by a movie like Halloween. “‘Oh, look at that guy—that evil guy there. Thank God it’s not me.’” FL

This article appears in FLOOD 9.