Arriving via private jet at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, Paul McCartney received a hero’s welcome you may assume he’s become accustomed to—but it was a far cry from the greeting on The Beatles’ only visit to the Land of the Rising Sun in 1966.

When the Fab Four arrived in Tokyo, they stepped off in Japan Airlines–branded happi coats, expecting the usual throngs of supporters on the tarmac, but instead were surprised by strict officials, with only a small group of pre-approved fans in attendance to greet them. The tour had become the subject of great national debate in Japan. Traditionally conservative attitudes were falling to the desires of younger progressives who wanted to use the group’s youthful exuberance to influence the nation.

The decision was made to move forward with the tour, but controversy remained, as five shows were booked at the Budokan, a traditional venue that until then had been reserved for martial arts. This further enraged the conservatives because of the arena’s status as a venue to commemorate the victims of World War II, and after a written death threat was discovered earlier on the tour in Hamburg, Japanese officials decided to mobilize 35,000 security officials in an attempt to guarantee the band’s safety.

Despite the show of force, passionate fans still tracked the band aggressively, as did ultranationalist student protestors, leading security to force the group to be confined to their suite at the Tokyo Hilton. Aside from the concerts, as well as one press conference, they were not authorized to leave the room. It was at this press conference that John Lennon spoke out against the Vietnam War, the first time anyone in the group had shared their anti-war views publicly. And in a further act of defiance, Lennon snuck all the way to the Harajuku district for some shopping—even stopping to sign an autograph for a fan—while Paul made it no longer than five minutes outside before being quickly wrangled and returned. In response, the band took to comically delaying the organizers’ military-like schedule. At the shows themselves, police worried about snipers and didn’t allow floor access for fans, warning that anyone standing or applauding would face arrest.

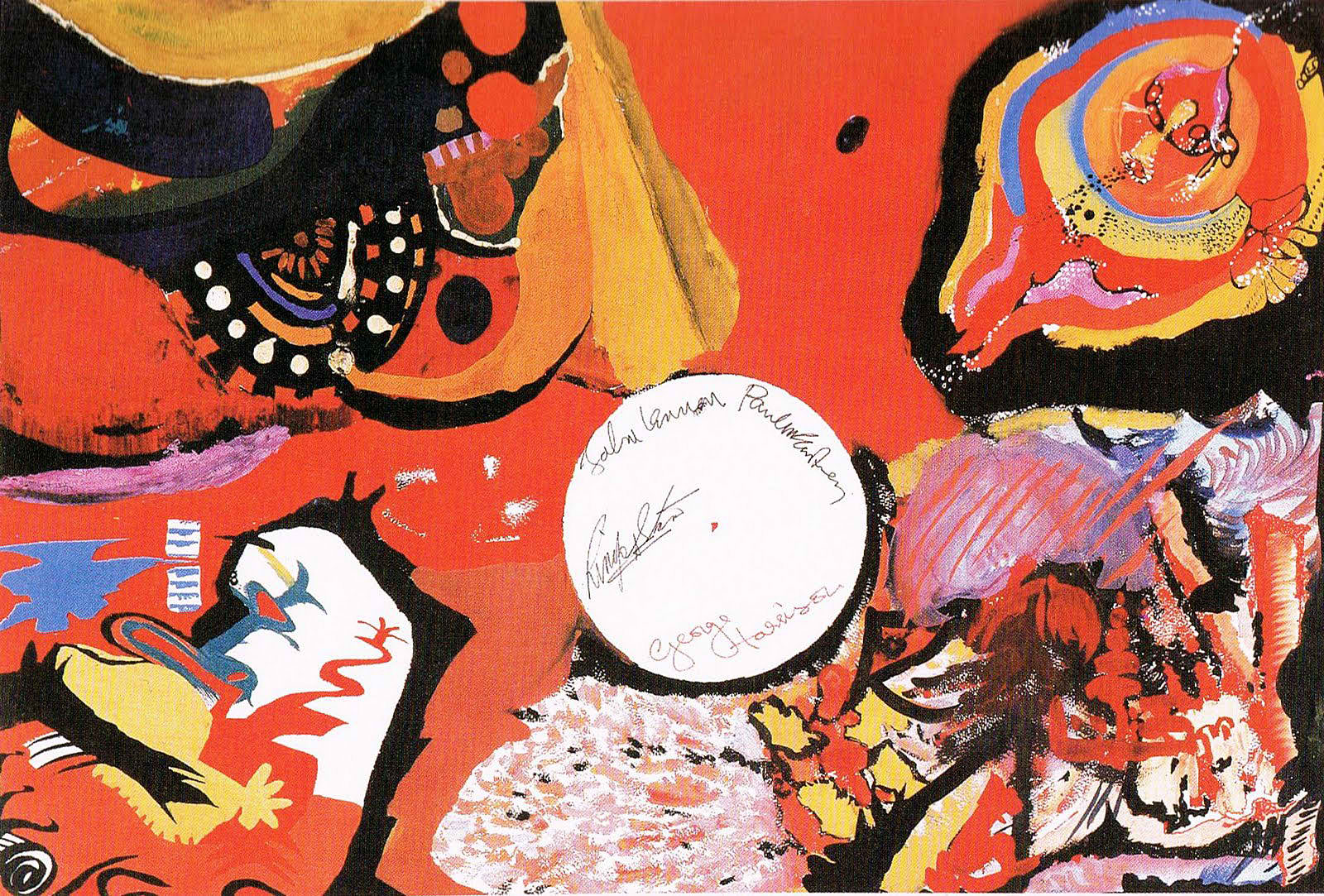

“Images of a Woman,” 1966 | The only collaborative painting the four Beatles ever did together

While confined in the Presidential Suite at The Hilton, Japanese promoter Tatsuji Nagashima delivered the group painting supplies to pass the time, leading to the four obsessively collaborating on a psychedelic painting that became known as “Images of a Woman,” The Beatles’ only group painting. Lit by a lamp placed on the center of a thirty-by-forty inch piece of paper Paul, John, George, and Ringo began each painting their own quarter. While they quietly painted by light, they decided on a name for their upcoming album: “Revolver.” Their tour photographer Robert Whitaker, who documented this artistic endeavor, later said, “I never saw them calmer, more contented than at this time. They were working on something that let their personalities come out. They’d stop, go and do a concert, and then it was, ‘Let’s go back to the picture!’” Upon its completion, they removed the lamp and each signed the white space where it sat. It was auctioned off for charity to a local fan club president, Tetsusaburo Shimoyama, and has since changed hands several times at auction, recently selling for more than $150,000.

Despite the controversy and limitations, that visit to Japan was considered a great success by their hosts. There, Beatlemania had been dubbed a “Beatles Typhoon, that swept the youth off their feet,” according to Japanese academic Toshinobu Fukuya, who also noted that the band demonstrated to the population that “one did not always have to obediently follow arrangements prescribed by adults; it was possible to follow one’s own path and still be socially and financially successful in life.”

The Beatles’ visit in 1966 demonstrated to Japan that one did not always have to obediently follow arrangements prescribed by adults.

In 1975, Paul McCartney and Wings planned a Japanese leg as part of the Wings Over the World tour was scrapped by officials over a 1972 Swedish marijuana arrest, and a 1973 marijuana fine from Scottish officials. When Wings eventually did get clearance to attempt a return in January of 1980, Paul ended up being detained after attempting to bring a half-pound of weed into the country at Tokyo’s Narita Airport. At the Tokyo Narcotic Detention Center, Macca became known as Inmate No. 22 as he faced nine days of interrogation and a maximum penalty of seven years hard labor.

Upon his negotiated release, a relieved McCartney said his detainment “was not too bad,” and even jokingly suggested he “might get a new song out of it, with some Japanese words.” Looking back on the episode in 2004, he admitted, “We were about to fly to Japan and I knew I wouldn’t be able to get anything to smoke over there, this stuff was too good to flush down the toilet, so I thought I’d take it with me.” Despite the amicable resolution, upon returning home, he made the decision to disband Wings, and they never ended up playing Japan after all.

Paul himself eventually did return to Japan in 1990, on The Paul McCartney World Tour, after which he donated the concert proceeds to charity. Playing six shows at Tokyo Dome, it was his big return after 1966. The trip formed a lasting connection, and over the years his passion for Japan grew; on return visits he regularly took in sumo matches and enjoyed bike riding through Tokyo’s many city parks. Since that time, Paul has played numerous shows in Japan, even returning to the Budokan in 2015 on the Out There tour, further driving a cult-like following in the country that had been denied his presence for so long.

So when Paul successfully passed through customs this week wearing a traditional happi coat adorned in a design inspired by his latest album, Egypt Station, along with his wife Nancy McCartney, it was a particular joy to the over five hundred adoring fans waiting to say hello. Upon seeing the masses, McCartney declared in Japanese, “Saiko!” which means “I feel fantastic!”

So when Paul successfully passed through customs this week wearing a traditional happi coat adorned in a design inspired by his latest album, Egypt Station, along with his wife Nancy McCartney, it was a particular joy to the over five hundred adoring fans waiting to say hello. Upon seeing the masses, McCartney declared in Japanese, “Saiko!” which means “I feel fantastic!”

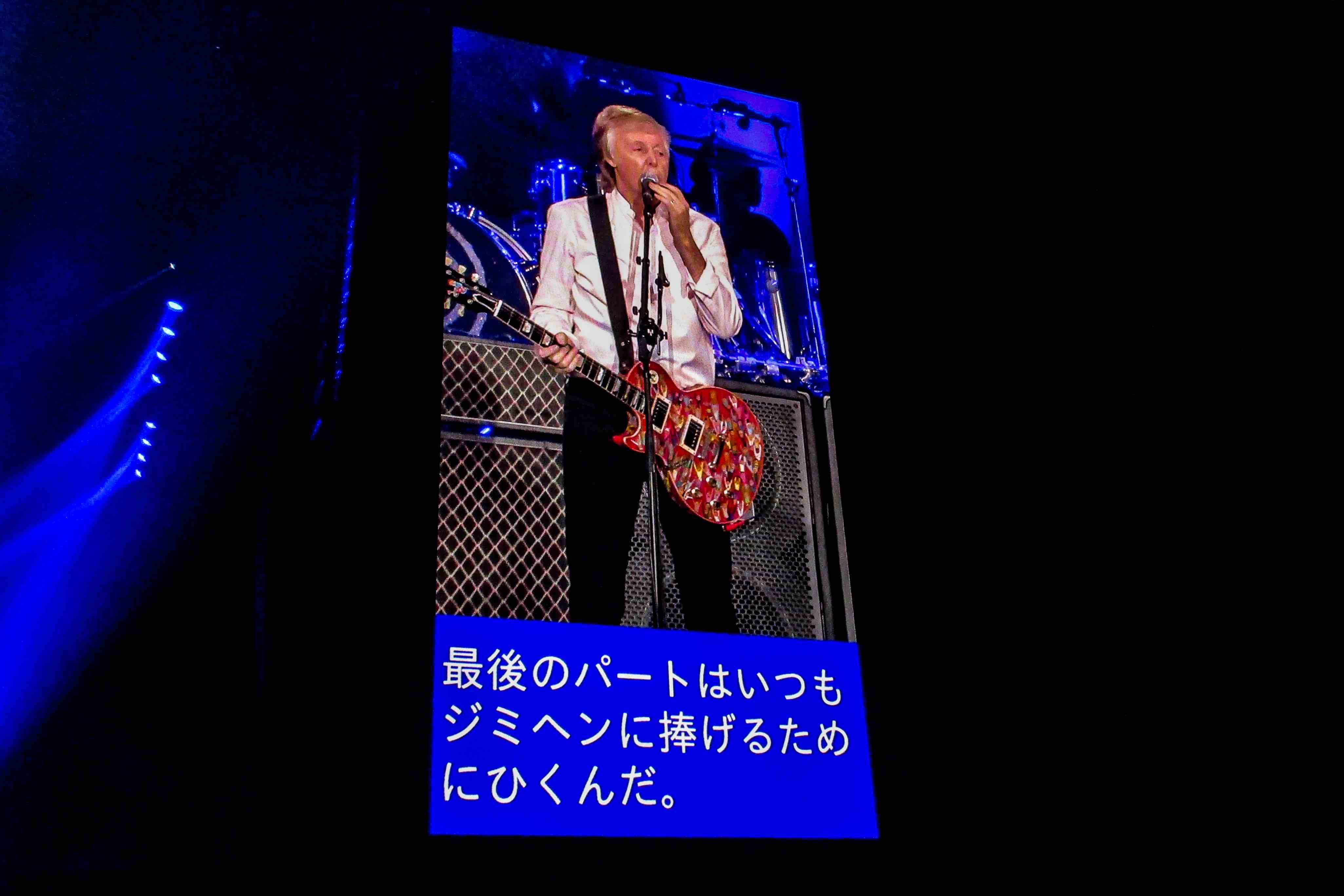

At his second sold-out show at the Tokyo Dome on November 1, McCartney was supported by on-screen translations, though he continued to trot out his attempts at the Japanese language a handful of times. At one point he asked the audience, “How’d you like my Japanese?” and following a tepid response he admitted, “OK, a medium?” He then tried the phrase again to a more thunderous response.

The massive Tokyo Dome crowd brought together generations of Japanese fans, from lifelong fan club members who attended The Beatles’ Budokan shows over fifty years ago to children whose parents weren’t even born then. The sometimes-reserved culture was once again wiped away by the Beatles Typhoon, and Beatlemania was alive and well.

An acoustic portion of the night found Paul transporting the audience back to those early days, trotting out “In Spite of All the Danger,” one of the first songs The Beatles ever recorded, “before we were even known as The Beatles,” he noted. The stripped-down section also included “From Me to You” and “Love Me Do,” both of which seemed to capture the purity of the original recordings. Paul recalled that while recording “Love Me Do,” the first song produced by George Martin, that he agreed to take on singing duties originally slated for John—and can still hear his nerves on the original recording. “Not tonight,” he reassured the crowd, before leading them in an affirming sing-a-long.

An acoustic portion of the night found Paul transporting the audience back to those early days, trotting out “In Spite of All the Danger,” one of the first songs The Beatles ever recorded, “before we were even known as The Beatles,” he noted. The stripped-down section also included “From Me to You” and “Love Me Do,” both of which seemed to capture the purity of the original recordings. Paul recalled that while recording “Love Me Do,” the first song produced by George Martin, that he agreed to take on singing duties originally slated for John—and can still hear his nerves on the original recording. “Not tonight,” he reassured the crowd, before leading them in an affirming sing-a-long.

When it came time for the Wings section of the show, the Japanese crowd made up for lost time, clapping at impressively perfect timing for “Band on the Run,” and throwing their fists in the air for the always impressive pyrotechnic explosions of “Live and Let Die.”

A celebration of the legacy of the world’s greatest band, a Paul McCartney concert is always an emotional experience. The universality of The Beatles’ message of peace and love transcends borders, generations, and even language. During “Hey Jude,” the song seemed to take on special meaning as Paul looked out at the seemingly endless sea of fans’ lights illuminating a chorus of “NA NA NA” signs, as even he was moved to a tear. FL