Last year, the announcement of a third movie in the Bill & Ted series was met with much excitement. Dean Parisot (Galaxy Quest) is directing, Steven Soderbergh is executive producing, and the long-awaited sequel will reunite Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, who starred in the original films. With Excellent Adventure turning thirty last month, we consider how it stands alone in the time travel genre.

What are the best time travel movies ever made?

The Back to the Future trilogy, for sure. The neverending Terminator franchise.

Then there are the classics, like Planet of the Apes and The Time Machine (the 1960 original, not the remake). There are the dark psychological dramas, like Twelve Monkeys and Donnie Darko. The sentimental romances, Midnight in Paris and The Time Traveler’s Wife, plus a few superhero movies, including X-Men: Days of Future Past, Doctor Strange (Rachel McAdams must really love starring in time travel movies), and probably the upcoming Avengers: Endgame.

There are the ones where people go back in time to stop themselves (Primer, Looper) and the ones where they’re trying to help their families (Interstellar, Arrival). In some films, time travel kicks off the plot (J.J. Abrams’ 2009 Star Trek reboot) while others keep you wondering if it’ll happen at all (Safety Not Guaranteed). There’s Groundhog Day, maybe. And in a similar vein, Edge of Tomorrow and Run Lola Run.

Different as they all are, most of these films have a few things in common, with characters either nostalgic for the past or regretting previous mistakes. Many of them express serious fears about time travel itself. It usually happens through some unreliable device (Click, Hot Tub Time Machine) or a machine that has never been tested and is possibly lethal (Déjà Vu) or is sanctioned by a government that won’t let characters die even if they want to (Source Code). Or, in a fascinating but depressing loop, everybody winds up being single, unhappy, and simultaneously responsible for their own conception and eventual death (yikes, Predestination).

But of the assorted time travel flicks of the last several decades, there’s one that didn’t waste time dwelling on doubts about technology or having to face down personal demons from the past. One that let audiences know the future need not be as terrifying as previously imagined. Actually, it could be most excellent, dude.

Few movies delivered the kind of time travel fan service Bill & Ted did—we see Beethoven rocking out on a stack of Yamaha keyboards, Joan of Arc leading the ultimate ’80s women’s aerobic cardio, and Genghis Khan going to town with a baseball bat and skateboard.

When Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure came out in 1989, it almost seemed destined to flop. This slacker buddy comedy, about two teenagers who create the world’s greatest history report through the help of a time machine, arrived at the end of a decade overflowing with flicks featuring similar characters (Fast Times at Ridgemont High and close to a half-dozen Cheech & Chong movies) and any number of time travel plots: Somewhere in Time, Timerider, Trancers, Star Trek IV (the one with the humpback whales), Flight of the Navigator, Peggy Sue Got Married, Timestalkers, The Time Guardian. The big pain for most time travel movies is having to spend time establishing how the process works, and detailing how characters are supposed to get there, come back, the assorted dangers, and so on. Meanwhile, characters work to dodge earlier versions of themselves or avoid creating “who’s your daddy?” –type paradoxes.

Bill & Ted threw all that out the window. There’s no explanation for how two San Dimas slackers are supposed to save the universe through their music. Or for why their time machine takes the form of a telephone booth—aside from that it’s presumably a similar shape to a futuristic giant crystal at the start of the movie it later morphs into—but then, what’s the deal with the giant crystal anyway? It doesn’t matter, because the audience is having too much fun to care.

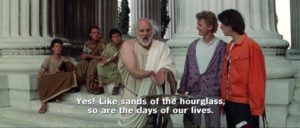

They’re getting the same kind of thrilling strangeness that Mark Twain provided in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, now considered (along with H.G. Wells’ Time Machine) to be one of the great-granddaddies of time travel sci-fi epics. Going into the past didn’t solely have to mean finding a way to bring about or avoid some apocalyptic future nightmare—it also meant an opportunity to meet philosophers from Ancient Greece, ride horse-and-buggies through medieval England, and gamble in saloons in the Wild West. Aside from Marty McFly (controversially) inspiring a future Chuck Berry in Back To The Future, few movies delivered the kind of time travel fan service Bill & Ted did—we see Beethoven rocking out on a stack of Yamaha keyboards, Joan of Arc leading the ultimate ’80s women’s aerobic cardio, and Genghis Khan going to town with a baseball bat and skateboard. The best is Sigmund Freud, unwittingly letting his corndog droop at two women who laugh at him in the mall.

Bill & Ted didn’t just subvert the time travel genre, it also challenged most screenwriting conventions. Our heroes don’t change over the course of the film and the audience doesn’t even get a full explanation for why anything’s happening until the last scene, when Rufus (George Carlin) finally explains his purpose for making sure Bill and Ted passed their history report. Up until then, the only hints regarding the plot are Rufus referring to the duo as “the two great ones” in the prologue, and the Three Supreme Beings of the Future—played by legendary musicians in their own right: Springsteen saxophonist Clarence Clemons, Motels lead singer Martha Davis, and Fee Waybill of The Tubes—giving Rufus the green light to help the teens because “their separation is imminent.”

Bill & Ted didn’t just subvert the time travel genre, it also challenged most screenwriting conventions. Our heroes don’t change over the course of the film and the audience doesn’t even get a full explanation for why anything’s happening until the last scene, when Rufus (George Carlin) finally explains his purpose for making sure Bill and Ted passed their history report. Up until then, the only hints regarding the plot are Rufus referring to the duo as “the two great ones” in the prologue, and the Three Supreme Beings of the Future—played by legendary musicians in their own right: Springsteen saxophonist Clarence Clemons, Motels lead singer Martha Davis, and Fee Waybill of The Tubes—giving Rufus the green light to help the teens because “their separation is imminent.”

For any storytelling gaps in the narrative, Bill & Ted makes up for it with a vision of the future that’s oddly prescient. We may not have flying cars or self-lacing sneakers in 2019, but we do have a virtual time machine—the Internet—where information about anything can literally be dialed up in much the same way that Bill and Ted did, through phone lines that would later become fiber optic telecommunication cables (“the circuits of history”). They access the past in the same way that you or I might access Wikipedia today.

Ironically, having unlimited access to the world’s collective knowledge doesn’t really change people, and the same goes for our heroes: despite summoning a mishmash of famous figures to help with their history report, neither Bill nor Ted seem to have learned a great deal about, say, the tenets of Freud’s psychoanalysis or Genghis Khan’s military campaigns. Thanks to divine technology, they don’t have to.

Ironically, having unlimited access to the world’s collective knowledge doesn’t really change people, and the same goes for our heroes: despite summoning a mishmash of famous figures to help with their history report, neither Bill nor Ted seem to have learned a great deal about, say, the tenets of Freud’s psychoanalysis.

Instead, Bill and Ted let the past literally speak for itself, while their contributions take the form of contemporary pop culture references. Ted describes Socrates as “like Ozzy Osbourne, [who] was repeatedly accused of corruption of the young.” Bill says that Beethoven’s favorite musical works “include Mozart’s ‘Requiem,’ Handel’s ‘Messiah,’ and Bon Jovi’s ‘Slippery When Wet.’” Their flashy stage show ends up being more performance than presentation—which is largely how modern audiences prefer to consume their history today, seen in everything from The Crown to Hamilton.

Even the plot structure of Bill & Ted moves like a there-and-back-again time machine. The story literally goes forward in one direction before hitting the middle and traveling backward, with scenes mirroring one another at corresponding points and playing out in reverse like a cinematic palindrome.

The movie begins and ends with Rufus, telling the audience about the impact of “the two great ones” in the future. The next scene (and the second-to-last scene) has Bill and Ted trying to make a music video in their garage. The third (and third-to-last) scene is about the history report, where they first learn they have to deliver an awesome presentation at the start of the movie, and then do so by the end. This is followed, and preceded, by Missy (Bill’s “cute” stepmother) driving them to/from school; Ted’s dad losing/gaining his keys; Bill and Ted aiding their past selves at the Circle K/in jail; and so on.

Moving in both directions from the movie’s midpoint (roughly around the time Bill and Ted meet Joan of Arc), Freud and Beethoven both get nabbed, and then so do Genghis Khan and Abraham Lincoln. The time machine also gets damaged at concurring points—first, by a knight swinging a mace, then later, from wear and tear—resulting in Bill and Ted visiting San Dimas in the distant future, where they share words of wisdom (“Be excellent to each other!”) with the Three Supreme Beings, then visiting San Dimas in the ancient past, where they share chewing gum with cavemen. We see Napoleon sliding through the time circuits behind the phone booth during the first act before seeing Napoleon sliding through tunnels at the water park during the second. Bill and Ted have to jump through hoops for Billy the Kid before he’ll help them, and around the same time later on, Bill and Ted (and everybody from history) has to help do the chores around Ted’s house before Missy will help them. The scene where Bill and Ted meet themselves outside the Circle K virtually plays out twice due to the overlap: “That conversation made more sense this time!”

Moving in both directions from the movie’s midpoint (roughly around the time Bill and Ted meet Joan of Arc), Freud and Beethoven both get nabbed, and then so do Genghis Khan and Abraham Lincoln. The time machine also gets damaged at concurring points—first, by a knight swinging a mace, then later, from wear and tear—resulting in Bill and Ted visiting San Dimas in the distant future, where they share words of wisdom (“Be excellent to each other!”) with the Three Supreme Beings, then visiting San Dimas in the ancient past, where they share chewing gum with cavemen. We see Napoleon sliding through the time circuits behind the phone booth during the first act before seeing Napoleon sliding through tunnels at the water park during the second. Bill and Ted have to jump through hoops for Billy the Kid before he’ll help them, and around the same time later on, Bill and Ted (and everybody from history) has to help do the chores around Ted’s house before Missy will help them. The scene where Bill and Ted meet themselves outside the Circle K virtually plays out twice due to the overlap: “That conversation made more sense this time!”

In the same scene, Rufus warns Bill and Ted they only have a limited number of hours to get what they need for their history report because “the clock in San Dimas is always running.” This seems strange, considering they have a time machine and could theoretically arrive any time they want. But from a scientific standpoint (namely, the relativity of simultaneity), Rufus isn’t wrong: time dilation occurs and varies depending on the position of a moving observer compared to a fixed position one.

Unlike the weirdly fading photograph phenomena of Back to the Future or being able to read a diary and “teleport” to past moments à la The Butterfly Effect, Bill & Ted utilizes basic quantum physics principles, like wormholes, with some accuracy.

That’s right: Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (sort of) gets time travel scientifically correct. Unlike the weirdly fading photograph phenomena of Back to the Future or being able to read a diary and “teleport” to past moments à la The Butterfly Effect, Bill & Ted utilizes basic quantum physics principles, like wormholes, with some accuracy. According to physicists (or at least one, CalTech theoretical physicist Sean Carroll, in a 2012 interview with io9), time travel as an actual possibility comes in two forms: predestination, where everything that happens—including going back in time—was always going to happen (which Bill and Ted capitalize on by stealing Ted’s keys so they could find them later); or the creation of a new alternate reality that emerges from new changes to the past (again, J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek reboot).

Alternate universes aren’t explored in Bill & Ted, aside from the future’s knowledge that the duo’s separation would either lead to the negation of the utopian world as it exists, or that it would create a new timeline where Ted goes to military school and utopia is (presumably) never achieved. But by posing this question for audiences to walk out of the theater pondering in 1989, Bill & Ted potentially helped shape a new generation of thinkers primed to believe in Mandela Effect–type conspiracies in 2019, where maybe we’re all living in some alternate universe ourselves. The idea of parallel dimensions has shifted from the science fiction fringe to the latest, Oscar-winning Spider-Man movie.

Put all this together and the unassuming Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure ends up achieving far more than most time travel movies, before or since. “You and I have witnessed many things, but nothing as bodacious as what just happened,” Bill says at one point in the film. Dude, you have no idea. FL