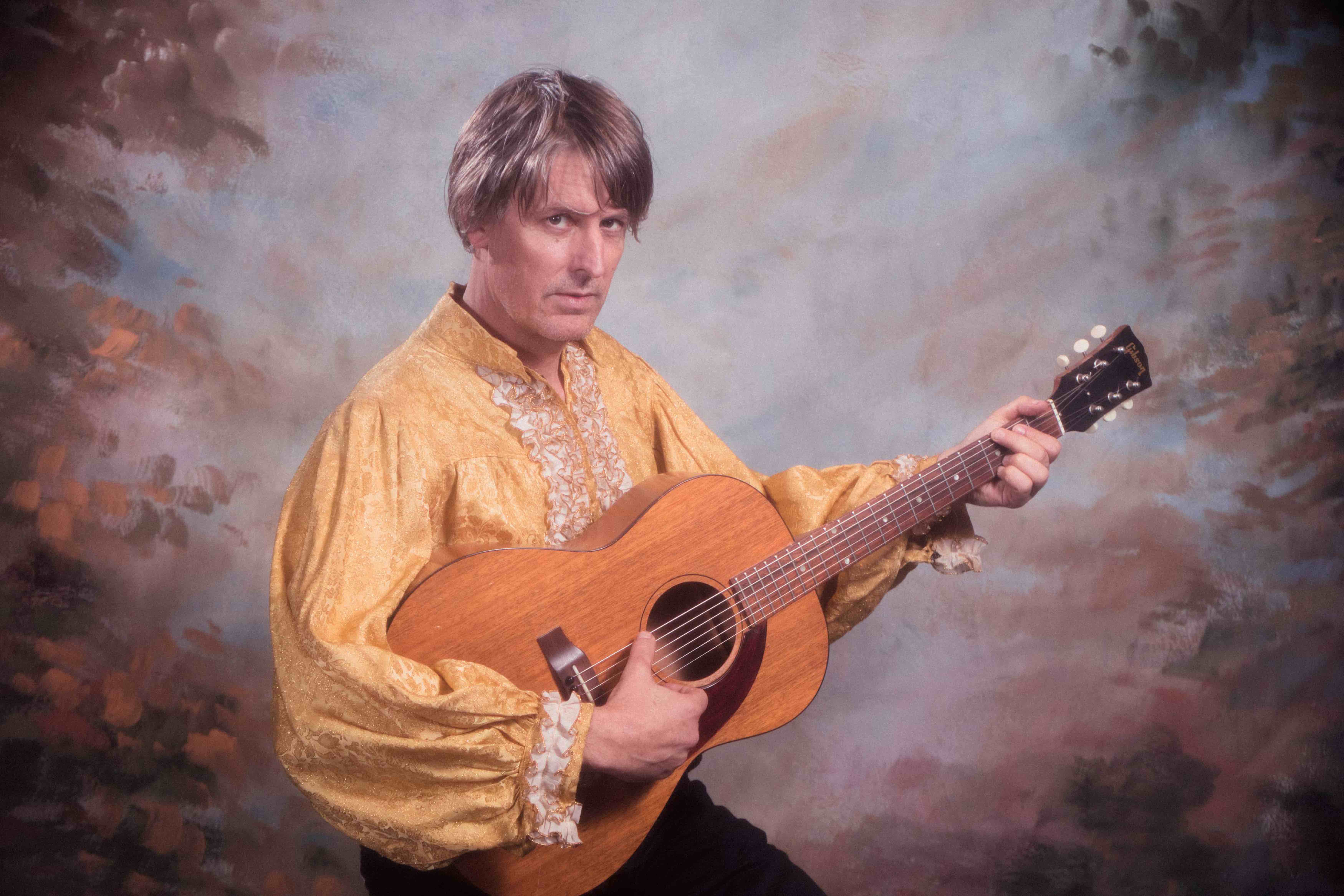

For the better part of the past twenty-five years, Stephen Malkmus has played a definitive role in indie rock, be it as leader of iconic ’90s slacker band Pavement or in his current stint with The Jicks. He’s gotten his lo-fi, fuzzed-out guitar rock sound down to something so recognizable and intrinsically him, that to move in a different direction seems implausible.

And yet, in the lead-up to 2018’s Sparkle Hard, Malkmus teased a solo electronic album that had been shelved in favor of Sparkle. An electronic album? From Stephen Malkmus? Prince of Slack Malkmus, who bears the nickname so well you can practically hear him shrugging from across the phone line when he finishes his sentences with a drawn-out, “I don’t know…”?

For most artists, the curveball album either comes early—often as an attempt to prove range after a breakthrough—or as an ironic side project for laughs. Still, there’s something to be said for the ingenuity of Malkmus’s experimentation at a point where many of his peers have settled into a pattern, releasing variations of the same song every two years before they can cash in on an endless string of greatest hits tours. For Malkmus, there’s a middle ground: he’s exploring other musical interests enough to keep things exciting, but not so much that the result is jarring.

“It’s the same person, obviously,” Malkmus says, “and the same things that you like stop you from going too far to do things that you don’t like—or things that are completely alien, that don’t work.”

On Groove Denied, Malkmus shows that “different” isn’t necessarily synonymous with “bad.” Across ten tracks, he serves up heavy doses of twitchy drum machines, icy synths, and stark vocals reminiscent of late-’70s post-punk, balancing the weird with just enough of his languid guitar-rock sound to keep it familiar.

Listening to Groove Denied is like hanging out with an old friend who just got back from study abroad. Sure, you used to listen to Dinosaur Jr. together, and now all he wants to talk about is Kraftwerk—but there’s an earnestness in his voice that makes you want to hear what he has to say anyway. After all, he’s still the same person.

What was your motivation for recording something so outside of the norm?

A couple things: I’m not a total, like, “Buy the new things all the time and get new pedals, new guitars” guy. Sometimes, just living with a family and a life, I can be satisfied with the status quo. I was pushed a little. I did the soundtrack music for this TV show on Netflix called Flaked, and that was an interesting experiment that got me to upgrade a lot of my stuff.

But it also got me thinking a combination of things. I’ve made demos a lot. Like most musicians, we do a first version of what we do and then we present it to the band and it goes through a super-ego editor situation. Ideally, you’re polishing it and getting feedback about what is connecting and then you record it together. So, I’ve done that kind of in a similar form for many years, virtually since 1996 or 1997, after [Pavement’s] Wowee Zowee. I was like, “Well, I’ve got this new stuff and I like other kinds of music.” And I just like looking for different ways to work.

There’s this relationship between fans and artists, where if you do too much of the same thing, fans react like, “Ugh, come on.” But if you do something different and it’s too different, it’s like, “No, no, no—don’t change like that.” The reaction to this has been pretty good. Were you expecting that, or were you expecting to put it out as, “If they like it, great. If they don’t, it’s what I wanted to do anyway”?

There’s a middle ground. Yeah, I want to be understood and liked and stuff. And it’s what you choose to put out. I do have other songs but I don’t know if they were good. They were more like the start of the album and some of those songs—pretty self-indulgent. In the end, I was trying to compile something to reflect this labor that I put in on all this stuff. I decided, “What is the best of this?” Ultimately, I just mixed it between things that were identifiable, but within parameters of home electric recordings. There’s some recognizable songs that fans would know and love if you’re following me.

Particularly as the album goes on, there are similarities between songs at the end and songs from Sparkle Hard. Was that a conscious choice, or were you working on them at the same time and it bled over?

[I was working on them] before. There were some demos that I recorded as if they were gonna be on this album—the songs “Middle America” and “Rattler” from Sparkle Hard. But it was a digital, more spooky Radiohead-version of [“Rattler”]. And then those sounded like they were just kind of strummy, acoustic sounding. It sounded like a demo and the other things didn’t.

"It’s potentially easier to do something by yourself, but it also could turn solipsistic and indulgent and also a little bit weak if you don’t have the muscle and the vibe of other people."

Being by yourself and without the support of a full band, how will going on tour work? How do you feel about it?

I don’t know. It’s very difficult to rehearse something like that without actually being in front of an audience and seeing how you react. I know that even in a place where I’m very comfortable, which is a dirty rock gig, you do rehearse in your place—but when you play, you act differently. There’s more reaction to the energy and these kind of corny things, but you’re just like, “Oh, people are actually here looking at me and they made an effort to get here.” It kind of ups your adrenaline and all that stuff.

I’m working on stuff to make it interesting. I’m going to see some other groups with backing tracks and try to determine what I like about backing tracks and what I don’t like. There’s a reason that bands with backing tracks, hip-hop bands even, have a drummer even though they don’t need one—just ’cause it heightens the drama and immediacy. You don’t feel like you could just be at home and you’re just seeing the body of the hero that you want to see [laughs]. How do you transform it into something more? There’s lots of things you can do. I could play dialogue. I could talk. I could just play guitar for a while, play old songs, reinterpret straight old songs. Some electronic things. I’m working on it.

You could take the shows in a super art-house direction.

Yeah, that’s true. I think the goal is to try and have a personal touch to it, that it’s something that comes from your mind. It’s maybe potentially easier to do something like that when you’re by yourself, but it also could turn solipsistic and indulgent and also a little bit weak if you don’t have the muscle and the vibe of other people. I’m hoping it’s good. I’ll learn. I’m trying to learn new tricks. FL