Cey Adams grabs a twelve pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon. Sitting in the 175-year-old brewing company’s downtown Los Angeles art space, the pioneering graffiti artist talks about the packaging he’s crafted for the beverage company.

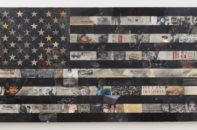

“I wanted to create something that, to the viewer, looks familiar—but then when you zoom in, there’s so much more context,” says Adams, who speaks with a sense of wonder and appreciation at the finished project, but not with conceit. “I’m making a piece of art, but at first glance it just looks like the Pabst Blue Ribbon logo; then you can look at this thing for hours on end and see things that are brand new.”

Adams’ layered and textured approach appears on 150 million PBR cans this spring, as well as the accompanying packaging. This is a staggering accomplishment for the artist, who emerged from Jamaica, Queens as a first-generation hip-hop graffiti writer and went on to work as Def Jam Recordings’ founding creative director, where he collaborated with the likes of LL Cool J and the Beastie Boys. He pored over decades of PBR’s archives to come up with his nuanced limited-edition designs.

The relationship between Adams and Pabst extends to their work on National Mural Day, which launches today, May 7, 2019. Adams is set to create a mural over the course of a few days in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and the company is also sponsoring the creation of more murals throughout the U.S., including in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Atlanta.

The relationship between Adams and Pabst extends to their work on National Mural Day, which launches today, May 7, 2019. Adams is set to create a mural over the course of a few days in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and the company is also sponsoring the creation of more murals throughout the U.S., including in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Atlanta.

“The beauty of murals and street art is that it’s on the wall, out there for the public to experience, and then they interpret it however they will,” says Adams. “Galleries and museums, that’s a whole other thing. But the work that’s out there, it doesn’t cost anything for people to go out and enjoy it.”

“The beauty of murals and street art is that it’s on the wall, out there for the public to experience, and then they interpret it however they will.”

As Adams reflects on his decades-long career, he recalls some sage advice given to him by the late artist Keith Haring.

“Keith was very aware of the power of his work, way before all of the acceptance and the fame came into play,” Adams explains. “He was somebody who taught me about being organized when people weren’t paying attention, just keeping track of all of your art and making sure that everything was dated properly and cataloged.”

For PBR, Adams wanted to bring the collage-based aesthetic he uses on most of his current artwork to the cans and packaging design. He sifted through early advertisements used to propel what is now America’s largest privately held brewing company into the forefront, drawn to the tightness of the original logo and its signature blue ribbon and accompanying red stripe.

For PBR, Adams wanted to bring the collage-based aesthetic he uses on most of his current artwork to the cans and packaging design. He sifted through early advertisements used to propel what is now America’s largest privately held brewing company into the forefront, drawn to the tightness of the original logo and its signature blue ribbon and accompanying red stripe.

“Now I understand the power of storytelling much, much more than I did when I was in my twenties,” Adams admits. “When I talk about the history of the brand, I’m interested in the storytelling aspect, and that’s the same aspect I was interested in as a teenager writing graffiti. Only now, I have a much bigger audience and a much wider platform. All of the graphics that are in this package are pulled from different places. There’s vintage magazines. There’s handmade papers that are made in India, in Nepal. There’s all of this craftsmanship that goes into making the actual art that you may or may not know. But if you talk to me, I’m going to tell you the story of where all these things come from.

“Then there’s the color palette,” he continues. “There’s something about the red, white, and blue that speaks to me as a New Yorker, as an American, and I think that’s something really powerful, just the way those colors jump off the package.”

As a visual artist who grew up in Queens in the ’60s and ’70s, specialized in graffiti, and worked with rappers, acceptance was gradual for Adams. When he first began traveling internationally in the 1980s, rap music and hip-hop culture’s demographic was much smaller than it is today. It was also age-specific.

“Now adults care,” Adams claims. “Back in the day, adults weren’t really checking for what we were doing. We were sort of communicating with the young people that were out and about who really dug what we were doing. It’s subculture stuff. It’s the same thing as skateboarding and surfing. You’re communicating to a very specific audience—but now that it’s going global, everybody is interested. You have people’s grandparents and you can speak to them about this work and they know what you’re talking about. They may not know every name of every artist, but they’re certainly familiar with how large it’s gotten and how lucrative it’s been, how accepted it’s been in museums and galleries.”

“Now adults care,” Adams claims. “Back in the day, adults weren’t really checking for what we were doing. We were sort of communicating with the young people that were out and about who really dug what we were doing. It’s subculture stuff. It’s the same thing as skateboarding and surfing. You’re communicating to a very specific audience—but now that it’s going global, everybody is interested. You have people’s grandparents and you can speak to them about this work and they know what you’re talking about. They may not know every name of every artist, but they’re certainly familiar with how large it’s gotten and how lucrative it’s been, how accepted it’s been in museums and galleries.”

Throughout his vast and varied career, Adams’ work has been shown at MoMA and at the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. While his early pieces were done behind the curtain of the art world, Adams embraces the attention he’s been getting with increasing regularity.

“It’s a long time since Run-DMC put out their first record, so to be a bridge from that period to today with something like Pabst to me is really cool,” he says. “I represent something much larger than myself now. I represent these brands that I’m working with, and I want people to know that the work I do is really important. I just want to make the brand proud, my family proud, my son proud. That’s the most important thing, I think.” FL

For more of Adams’ work, check out the gallery below.

- photo courtesy of the artist

- photo courtesy of the artist

- photo courtesy of the artist

- photo courtesy of the artist

- photo courtesy of the artist

- photo courtesy of the artist