BACKSTORY: picked up a camera when she was twelve and started making horror movies and commercial recreations with her cousins

FROM: UK-born, US-raised, LA-based

YOU MIGHT KNOW HER FROM: many best of 2014 lists and a recent Spirit Award nomination

NOW: preparing to release Girl’s accompanying kickass soundtrack and graphic novel series.

There are three things that Ana Lily Amirpour evidently loves: film, music, and comparing those two things to sex. She’ll try and explain why the wholehearted consumption of music and films like Pulp Fiction are like good sex, but notes that good sex “is not a hundred percent guaranteed.” Film and music, however, are always guaranteed (“a song is crazy because if you love it, you just want to crawl inside and live there”). Her debut feature, the western-inspired foreign-language vampire film A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, is an intimate portrayal of the passion she has for both.

The film is very much a creation of Amirpour’s own mind, the details of her personal obsessions craft the film’s fantasy world of Bad City, a vice-plagued ghost town. “I knew there was a pile of dead bodies in this town, and lots of prostitutes and a pimp-gangster kind of running things,” she describes. It’s a perfect place for the titular Girl—a music-loving, skateboard-riding vampire—to feed off the misogynistic and corrupt, set to a killer soundtrack, of course, ranging from Middle Eastern indie rock to ’80s electropop.

Despite Girl’s hallow tone, there’s a search for human connection in the dreary loneliness. The beginning of the film portrays the detached interactions of the Farsi-speaking cast, focusing on the James Dean–esque Arash, his drug-addicted father who has mentally checked out, the gangster-pimp who is only interested in sex and money, and the prostitute (whose part feels like the loneliest of them all). When The Girl is introduced, emotions and vulnerabilities arise, most evident in the blossoming romance between her and Arash (the most memorable and Shazam-worthy moment is when they’re listening to a White Lies record in her bedroom). It feels like what Amirpour would describe as a “very rare, specific moment of magic where this thing happens, and a connection happens.” It’s inexplicable, but it’s moving. “[That magic] is always this ephemeral, fleeting thing and then you go back into your singular brain cave,” she says. And it’s an idea that resonates in the lives of these people.

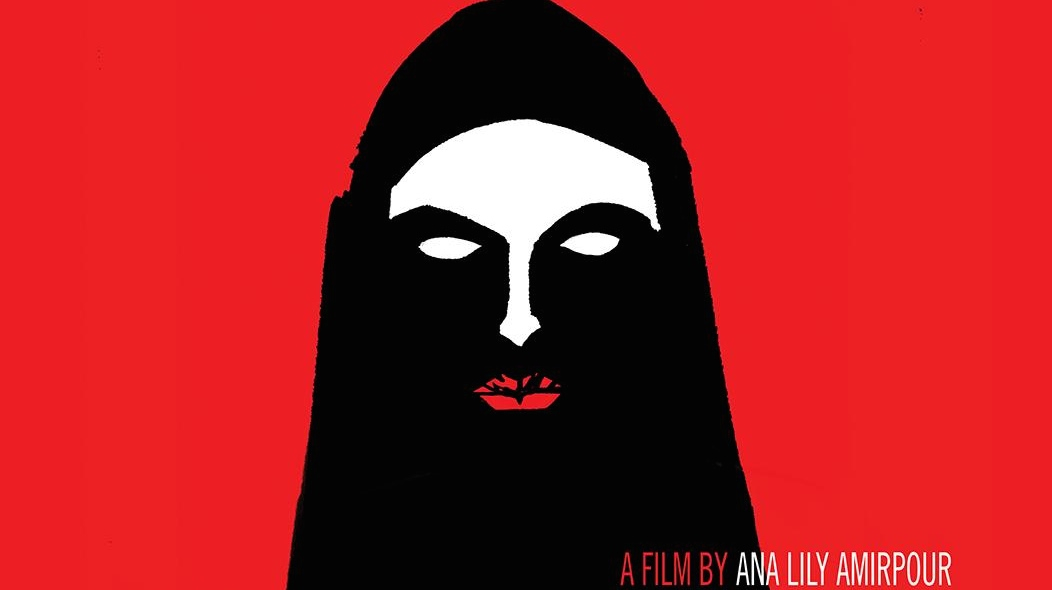

Sheila Vand as The Girl, in A Girl walks Home Alone At Night

The importance of this connection extends beyond her characters and seeps into her relationship with the cast and the film. “You start bringing people in and you’re looking for spiritual warriors who will connect because it’s starting from something that’s meaningful to me. It’s almost like bringing people into your brain caves and then their brain caves are inside your brain caves.” Filmmaking becomes an intimate process that comes “from a place of wanting to gut myself and show something that’s inside—or reach in and grab my own heart and see what it looks like. I just want to see what’s in there and show it and be like, ‘Am I all right? Do you get it?’” Amirpour’s film is more than an invitation into her mind; it’s her heart on display.

“I feel like Doc Brown from Back to the Future,” she explains. “He’s a mad man. And it’s almost like you become a mad man with a purpose [when you’re making a film]. Like if it ends up in a theater and people watch it, there’s a purpose. A film is an invention. So Doc Brown is an artist, he’s an inventor. The DeLorean has to work.” FL