In a few short years, Brazil’s Boogarins have come a long way—both literally and metaphorically. Founded in Goiânia, Brazil in 2013 by childhood friends Benke Ferraz (guitar) and Dinho Almeida (vocals/guitar), the band has been crafting sumptuous and often politically inspired psychedelic pop that’s evolved in scope in the short time they’ve been together. And while Boogarins started as a two-piece, they’ve since doubled in size, augmenting their line-up with bassist/synth player Raphael Vaz and drummer Ynaiã Benthroldo.

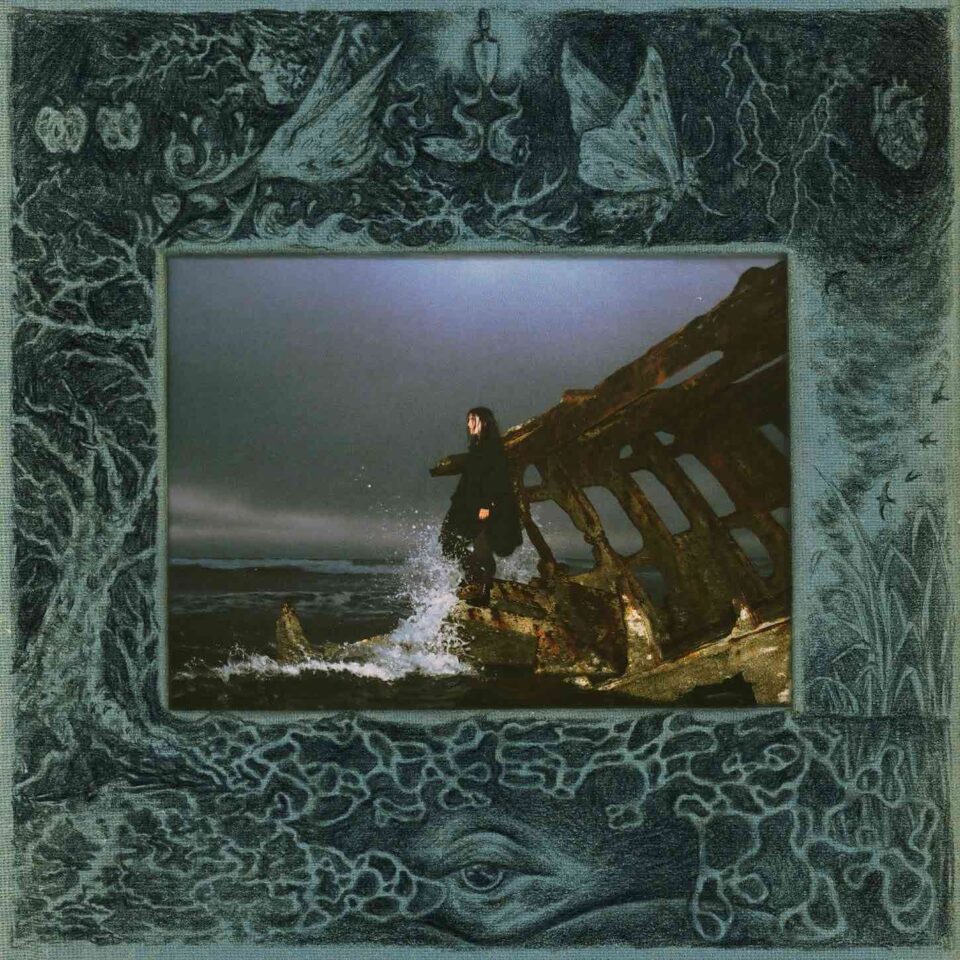

Their fourth album Soumbrou Dúvida is the band’s most ambitious and expansive collection of music to date. A contraction of its title track, “Sombra ou Dúvida”—which translates from the band’s native Brazilian Portuguese as “Shadow or Doubt”— Soumbrou Dúvida seems to mark a new phase for the band. But what phase that is, exactly, neither Ferraz or Almeida are quite sure.

What is certain is that Boogarins have transcended the seemingly limiting nature of playing experimental music and singing in their own language to create songs that are truly universal. The band has already toured with big-name American acts like Guided by Voices, Neutral Milk Hotel, and Of Montreal, and are breaking down even more barriers with their newest set of songs.

What does this album mean to you?

Benke Ferraz: It’s been five years since we really started touring, and it’s our first well-produced album where we went to a big studio with a big engineer [Gordon Zacharias]. Before this album, we were thinking that we had to deal with every moment and every step of the sound, which was holding us in a certain lo-fi box. This album is a step forward. It sets a new standard for us in the way we approach music and touring. It’s the first album of a new era—until now, it’s like everything was just a blur. I think we’ve been in a hurry for the last five years, working a lot, and the album on which we decided to have a proper engineer and someone from the outside to collaborate with and help us go into a proper studio is also the album that sounds closest to what we wanted to reach.

Dinho Almeida: This album is a great accomplishment for us playing together—even for me to see how much better Benke is getting when it comes to mixing and production. We’re getting better at showing the crazy stuff that’s going on inside our heads. It should make you think a lot about living today with how bad things are—and how that all fucks up how you live and understand stuff. It fucks up our sensibilities. It’s about that big wave of information we receive and don’t know how to process at all.

Are you surprised at the way you’ve connected to people outside of Brazil?

Ferraz: At first we were surprised, yes—but also, not really. I was confident about the first album. That’s why I started sending it out to as many people as I could and looked for websites and labels. I felt the songs I was doing with Dinho back then were special. I knew about the psych movement and doing sounds that were retro but also futuristic, and that’s what I was basing myself in—that’s a kind of global scene. I started sending stuff out and six months later we had the album released on vinyl and were touring with Guided by Voices and Neutral Milk Hotel and Of Montreal—and that was crazy! But we didn’t really have enough time to be impressed by what we’d accomplished. It was more like, “Who else should we convince that we’re doing something special?!” It was both luck and a lot of hard work.

“We grew up listening to The Beatles and all this classic stuff that’s not from Brazil, and I think when people who don’t understand Portuguese like our songs, it’s because they feel stuff.”

—Dinho Almeida

How important is it to you that people understand what you’re singing about?

Almeida: I think it’s important. I don’t think I have to make people understand what I’m singing, but I want them to be able to feel and try to get in touch with what we’re saying. We grew up listening to The Beatles and all this classic stuff that’s not from Brazil, and I think when people who don’t understand Portuguese like our songs, it’s because they feel stuff. Now I’ve picked up English a bit better, but there are still things I listen to where I don’t understand a word they’re singing—and it still moves me and makes me feel something. I think music is pretty much about that. Of course I care about words, and I don’t like to just write whatever, but I really think that music is a language in itself, and whether it’s in English or Spanish or Portuguese or French, it’s just texture.

Soumbrou Dúvida has a very ambitious sound. Do you think you could have made this in your early years?

Ferraz: With every release, we’re learning. The first was really DIY and the second we went to a proper studio, but an all-analog studio. We were young and we didn’t really know what that meant, and we were trapped in a way of recording that’s pretty much what we do live. After that, we went to a house and rented equipment. So every step was important for us to get to this sound now.

Did you write much of it in the studio?

Ferraz: Yes. That’s something that’s also really different about the way we did this album. Most of the songs were written on an acoustic guitar, and we’d bring all the pieces together in the studio. It was like a process of a song a day, and most of the time we were starting from scratch. Usually our pre-production is our production! Also because we improvise a lot, we’re always coming up with new songs, even if they’re just ideas that we repeat and record and listen to and then say, “Oh, there’s a good idea here.” So we’re always looking ahead—we produce as much as we can and put the final touches on it afterwards in post-production. I think now we’re more aware of what we can do in terms of the level of songwriting, and with our instrumentation and arrangements. We’re getting closer to the point where we can just go to the studio and record our live arrangement and I don’t have to mix or post-produce anything—mixing and all that kind of stuff can be done by professionals and not by crazy artists.

So what comes next? This record only just came out, but do you know where you go from here?

Ferraz: I think so! We started producing the next thing already—from the recording session for Sombrou Dúvida we have eight or nine tracks that are not on the album and we’re kind of doing the same process of post-production on those already. We’re going in a more serious way—something that is even more aggressive than what we did on Sombrou Dúvida. The last song we recorded was the first single we put out—“Sombra ou Dúvida”—it’s like the heaviest and most dangerous song on the album. And even though we’re going all over the place, and I’m not sure what’s coming next, I think we’re going in that direction.

Almeida: I don’t know if this record is the start of an era like Benke said, but I think it’s an important step for us and a good way for us to prove that we can do a lot of different kinds of music. And we want to experiment more and more. It’s really hard to make a living in Brazil from just playing music, but if we can continue to make people feel stuff with ours, I’d like to do that for my entire life. FL