Though my first youthful image of Bob Dylan was that of the spindly, thin man decked in black with teased and scraggly hair, my entry into who he was, sonically and lyrically, came with the triple play of Blood on the Tracks, The Basement Tapes, and Desire. Released between 1975 and 1976, the record of a stinging divorce and its emotional detritus, a messy but majestic bit of Americana, and an album based on one man’s fight for freedom painted a collective portrait of a poet at his full-flower, in command of his choices.

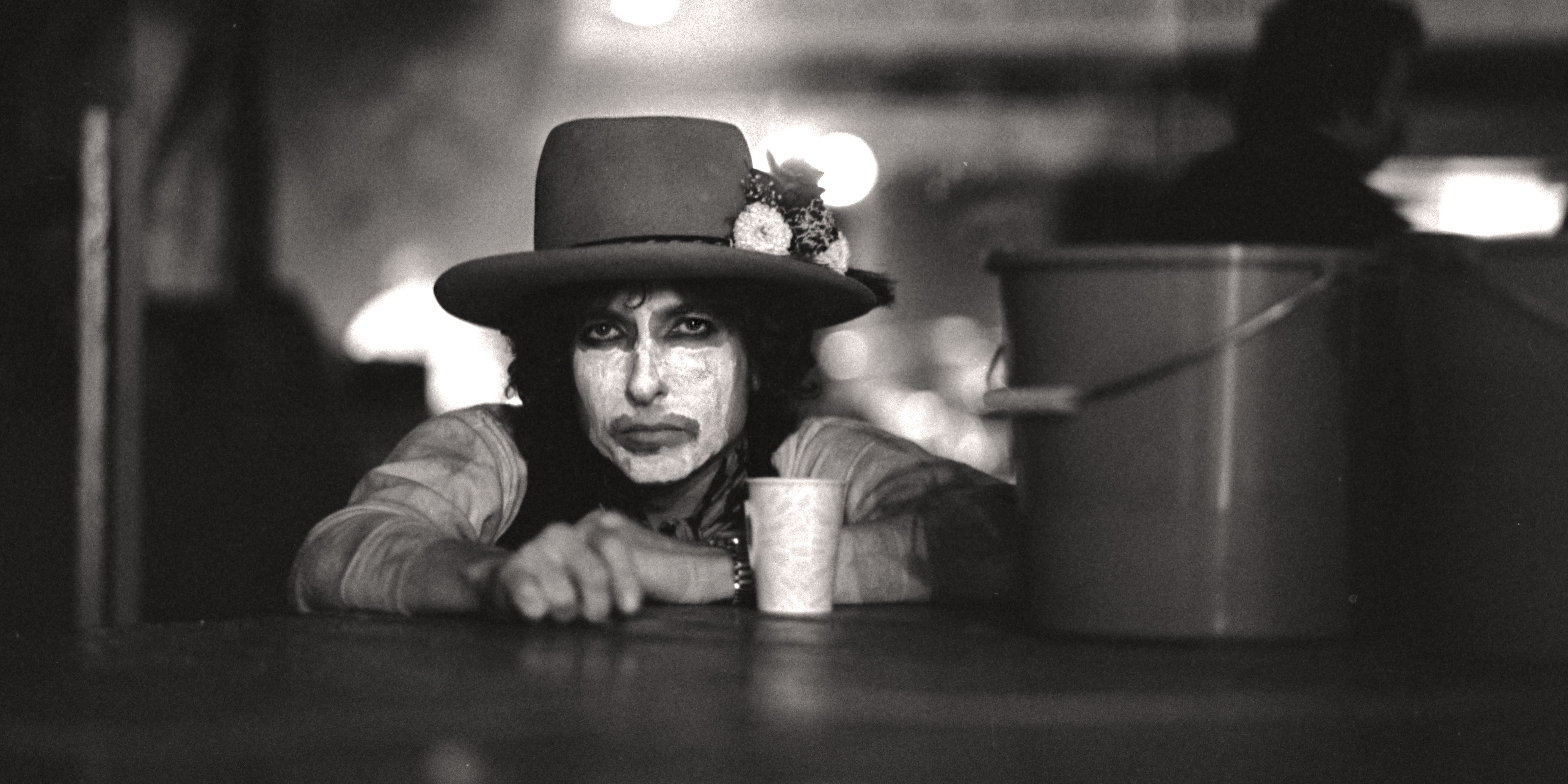

So, why not choose to gather together friends, old and new, for a shambling, theatrical caravan, one where its centerpiece is dressed in feathered hat finery, wearing ghostly white pancake make-up, and pushing glam guitar god Mick Ronson to add his razor-sharp twang to the proceedings? That image and those tones are at the heart of both Columbia’s The Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings and Martin Scorsese’s Netflix documentary Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story.

Since its brief time in the sun—small theater and lodge dates in 1975, and again the following year, rather than twenty-thousand-seat arenas—the Rolling Thunder Revue has become a mythic chapter in Dylanology, aided by the fact that authors Allen Ginsberg (at Jack Kerouac’s grave in Lowell, MA, no less), and Sam Shepard, old folkies Joan Baez and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, soulful young punks T-Bone Burnett and Patti Smith, and foul-mouthed Kinky Friedman all became part of Bob’s tribe for this travelogue, at a time when Dylan was at his most forceful, dramatic, and playful.

This chimerical tour-tale is made all the more phantasmal due to Dylan’s usual cryptic nature. When asked by Scorsese near the start of this—their second documentary together—to recall any worthwhile memories of the tour, Dylan answers quizzically. “I don’t remember a thing about Rolling Thunder. It happened so long ago I wasn’t even born yet.” Dylan waits a beat, and continues: “So what do you want to know?”

As he has throughout his career, Dylan is provoking the listener-viewer with a promise of knowledge, the inside game. Maybe even a lie or two to lure you and his collaborators in, just like when he told fellow Greenwich Village folkies at his start in a New York City coffee house that he had been in a circus in his youth (he was saving that circus for Rolling Thunder). Only then, once he has you in his grasp, do you realize that he’s saying everything while revealing nothing.

When it came to the Netflix documentary, Scorsese rounded up the usual suspects (Baez, Shepard before his passing), found a treasure trove of concert footage, (Dylan shot much of his tour’s stops), and included the baffling bits of fragmented dialogue that comprised the rambling feature film Renaldo and Clara and professional home movie footage of Dylan driving tour RVs, hanging in graveyards, rolling around Ginsberg’s Lower East Side apartment, bounding and bouncing into backstage areas, and rehearsing in weird spaces like old age homes during mah jong tournaments. These behind-the-scenes moments feel as frenetic and goofy, at times, as a Monty Python silly walk—particularly when the backstage cameras zeroed in on Dylan. Though he feigned shyness, remoteness, and craving privacy—his default settings—he did it with theatrical elan, always. Who hires cameras just to turn their back on them? Then again, who tells Scorsese he remembers nothing about Rolling Thunder, save for the fact that it was a commercial flop?

And then Scorsese gets really strange. The film simultaneously maintains a childish, menacing, and psychedelic air (all he shot were the new interviews) of fact-meeting-fiction, cinéma-vérité with a mad dash of Fellini, for something that feels like The Departed meets Hugo meets Public Speaking, the director’s 2010 examination of the work and life of writer Fran Lebowitz.

Rolling Thunder’s ferocious live stuff is sumptuous to behold, as warm, haunting, and bathed in deep crimson tones as any Scorsese Little Italy bloodbath.

There’s even a made-up subplot (is it Marty or Bob who insisted on that?) featuring Sharon Stone as a tour hanger-on, and actor Michael Murphy as the footage’s initial director for laughs. Is it funny? Not really. Is it culturally relevant, considering there is a pre-Reagan, socio-political tie to the tenor of the ’70s with quotes from Jimmy Carter, a discussion of Hurricane Carter’s imprisonment, and such? Yes. But that, too, seems slapsticky, considering that Murphy played politico Jack Tanner in Garry Trudeau and Robert Altman’s 1988 mockumentary showcase, Tanner ’88, and the actor appears here under that name. The entirety of Rolling Thunder’s slapdash oddity feels at one with the original backstage footage and the air of myth lent to the proceedings by the late, great Shepard during his new-ish interview portion.

As the concert footage was professionally filmed, Rolling Thunder’s ferocious live stuff is sumptuous to behold, as warm, haunting, and bathed in deep crimson tones as any Scorsese Little Italy bloodbath.

Looking as chipper and bright-eyed (all that mascara he’s wearing must have helped) as he sounds, any vague mythology that Dylan may have held becomes rock solid, rolling, and loud (Scorsese loves loud—watch Goodfellas right now and tell me it doesn’t roar with music). Perhaps the theatrical device of masquerading as a preening Poirot, or having a crowd close around him on stage and off, gave Dylan the necessary gumption and agility—but this was live, Dylan at his ballsiest and most sensuous. When he duets with his old lover Baez on stage, this isn’t kiddie kismet. It’s nearly carnal, watching two adults in an embrace that is as much poetic song as it is sexual grace (there’s also a scripted bit with the twosome from Renaldo and Clara where Baez quizzes Dylan as to why he never tried to marry her for a total bit of meta-mind-fuckery).

The fourteen-CD Columbia label box set, The Rolling Thunder Revue, is a delirious companion piece to the Netflix doc with its own brawny business to tend to.

Capturing several in-depth and lengthy rehearsals at the famed S.I.R. Studios, and occupying three of the box’s discs, you can hear that not all of Dylan & Co.’s staged sessions were so impromptu. Whether it be complete takes on the blowsy “Rita May,” or incompletes such as “Rake and Ramblin’ Boy,” “Romance in Durango,” and “I Want You,” you can hear a team striving for empowerment at all costs, truly going for it. Plus, you can hear tinges of Dylan’s religious period that followed this by a decade in rehearsal takes on “People Get Ready” and “What Will You Do When Jesus Comes?”

By the time you get to the five-tour stop recordings that Dylan professionally taped, the group—shambling as it might seem—is armed and ready to attack with Dylan as it rangy, roaring general. And while Scorsese’s documentary footage depicts Baez as the alluring temptress, it is violinist Scarlet Rivera—a woman as mysterious as Dylan—who provides the sonic counterpoint to Bob’s forceful howl here.

While Scorsese’s documentary footage depicts Baez as the alluring temptress, it is violinist Scarlet Rivera—a woman as mysterious as Dylan—who provides the sonic counterpoint to Bob’s forceful howl on the box set.

Like the Desire album they broke from to tour as the Rolling Thunder Revue, Rivera’s spooky Romani-gypsy sawing—a fleshy soulful tone that both compliments and echoes the singer’s wail—is the box set’s sensual centerpoint. Whether you listen to the tough and torrid “Hurricane” and its slow, stirring equal in “One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below)” from Cambridge’s Harvard Square Theatre (November 1975) or “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and a hypnotic “Isis,” from Boston Music Hall, you’ll hear Dylan and Rivera at play in the fields of the Lord, at empty dinner tables and in bedrooms, battling it out romantically and righteously.

The one thing the live box doesn’t do that the documentary does is show off the Revue’s other revuers. Joni Mitchell, in particular, an artist who was rumored to have long intimidated Dylan, does a magically haunting performance of a then-newly written “Coyote” with Dylan and Roger McGuinn backing her at Gordon Lightfoot‘s house in Canada. A childlike Patti Smith damn near steals the show during her brief moment in the pre-Revue rehearsal Greenwich Village spotlight. Then again, Scorsese’s documentary doesn’t capture Dylan’s restless rehearsals or its rarities such as Merle Travis’ “Dark as a Dungeon” and Irish folk traditional “Easy and Slow.”

You could get hacky and say, “collect the entire set”—and still, somehow, it wouldn’t be enough. Because for all that, nearly three hours of film footage and fourteen CDs’ worth of ferocious live music, even narrowed down and plucked from one year of Dylan’s life, you can’t get there from here.

“Life isn’t about finding yourself, or finding anything,” said Dylan during one of the film’s interviews. “Life is about creating yourself.” FL