Welcome to Rearview Mirror, a new monthly movie column in which I re-view and then re-review a movie I have already seen under the new (and improved?) critical lens of 2019. I’m so happy you’re here.

American Beauty. American Beauty! American Beauty? American Beauty…a title so vague the movie must be a classic, a manifesto, a touchstone, an urtext—and it is, in its way. Written by Alan Ball and directed by Sam Mendes, the film came out in 1999. It’s “sexy teen” Amy Fisher combined with disaffected Kurt Cobain and set against the backdrop of the high school from Daria. It’s got the cubicles-are-hell ethos of Office Space and the intersecting storylines of Magnolia, both of which also came out in 1999. It was either the pinnacle of a decade of exploring the underbelly of the American Dream, or the final nail in the coffin of the suburban discontent movie, depending on your take. It’s so representative of its time that it’s hard to see it as its own thing. A thing that is, essentially, a downer fable about unhappy white people. But a very well-done downer fable about unhappy white people.

There are so many elements that still work. The performances are fantastic, the script full of darkly comedic moments, with the best standalone lines given to Annette Bening (“You ungrateful little brat! Just look at everything you have. When I was your age, we lived in a duplex!”). But it’s also deeply self-serious. Neither ironic nor sentimental, the tone is something akin to…wisdom? A profundity I’m not sure it really earns. The movie stops short of moralizing, but it’s still trying to teach me something. From the unsubtle symbolism to the narration to the many, many slow push-ins on one-take scenes, it’s a little like your dad sitting you down and playing you his favorite record and watching you to make sure that you’re getting it and appreciating it because this is real music, and the stuff you like sucks, but now you’re going to develop taste. (Which, thankfully, my dad never did, which is why I listen to garbage.)

And there’s nothing more self-serious than a teen girl with daddy issues. The film opens with discontented suburban high schooler Jane (Thora Birch) lazily describing how much she hates her father, a loser with a hard-on for her best friend. She’s addressing an unseen guy who is recording her with a camcorder, and when he offers to kill her dad, she accepts. And in case you forgot, this is 1999, just months after killer teens became a nationwide fascination following the Columbine Massacre. Will this be Jane’s version of the basement tapes?

The point of view switches to the omniscient voice of beyond-the-grave Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey), Jane’s father and our protagonist/narrator, who reveals that he will die in less than a year, setting up the first of the movie’s handful of fake-outs. It’s sort of a cheap gimmick, to hook the audience with a whodunnit and implicate the daughter, but soon enough the movie’s focus shifts to how Lester is “already dead” inside because he is so unhappy. He hates his job. He hates his wife. His daughter hates him. He jerks off in the shower, and it’s the best part of his day, and that’s so pathetic.

Lester is still, mentally, in high school. His wife is his mom, making rules he doesn’t want to follow. His job is homeroom, assigning him homework he doesn’t want to do. He pouts and won’t eat his dinner, getting ice cream instead. And of course, he’s got a crush on the prettiest girl in school.

Lester’s wife Carolyn (Annette Bening) is a real estate agent who channels her unhappiness into growing red roses, but every rose has a thorn; you get it. Jane is unhappy because her parents are ignoring her, so she wants to buy a little attention in the form of a boob job. Their next-door neighbors are happy homosexuals, both named Jim, and their other next-door neighbors are…hold off, we haven’t really met them yet.

It was either the pinnacle of a decade of exploring the underbelly of the American Dream, or the final nail in the coffin of the suburban discontent movie.

Carolyn’s trying to sell the American dream one home at a time, but what starts off as a promising up-by-your-bootstraps kind of day (“I will sell this house today!”) quickly sours as potential buyers catch on to the fact that really, it’s just a crappy little house. Carolyn trying, and failing, to sell this house works well as its own little short film, and when she finally breaks down in tears and slaps her own face, you can see why Bening got the Oscar nomination. I’ll also note that the real estate sequence is the only part of the movie that includes anyone who isn’t white, and one of those not-white people is young John Cho. I friggin’ love John Cho!

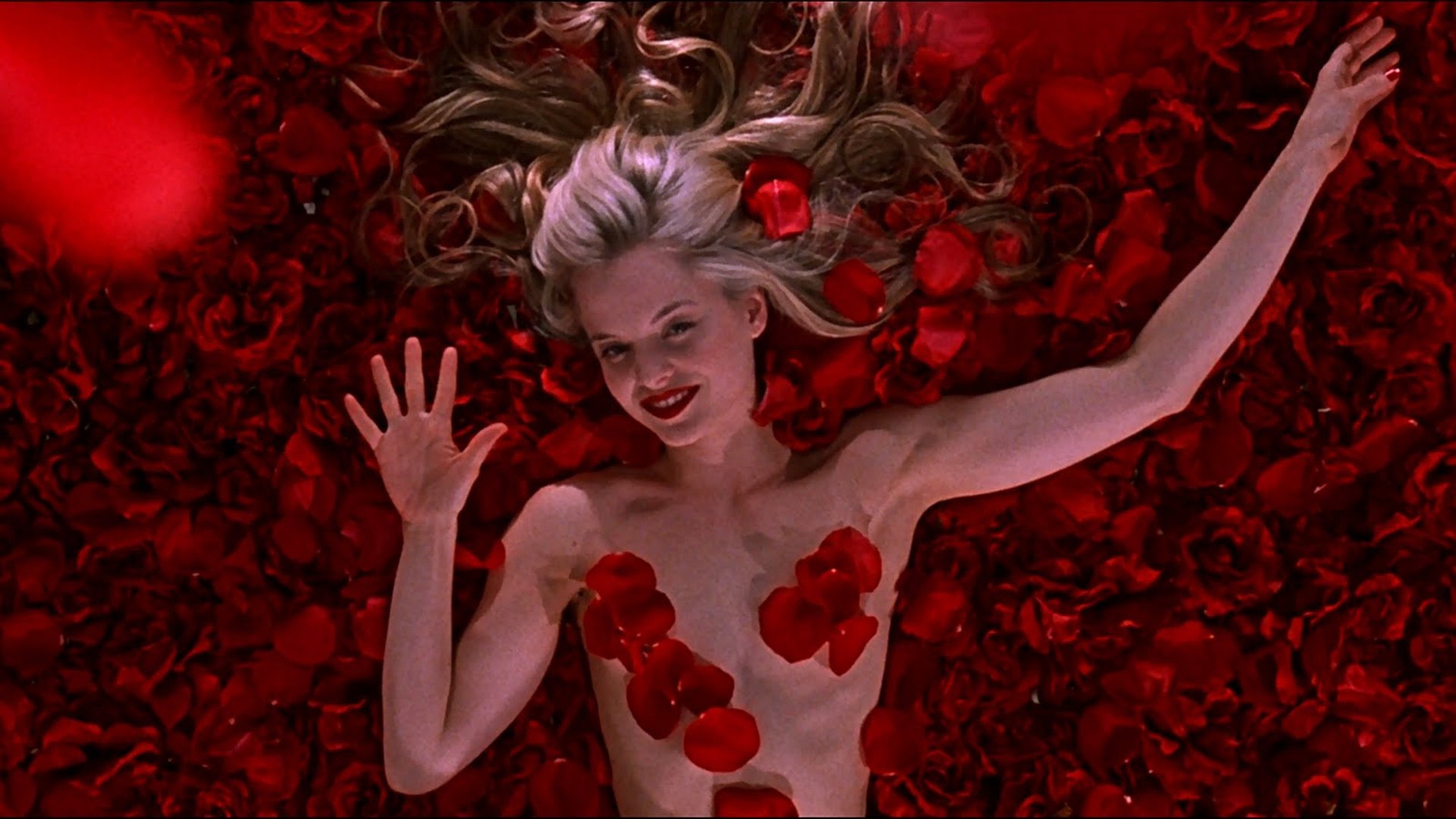

Though they don’t seem to particularly like their daughter, the Burnhams know they are supposed to watch her perform at half-time at a school basketball game. While Carolyn watches Jane (“I watched you very closely; you didn’t screw up once!”), Lester falls head-over-scrotum in lust with Jane’s best friend, a snarky blonde named Angela Hayes (Mena Suvari). Angela as in Angel; Hayes as in Haze, as in Dolores Haze, as in Lolita’s name. Though his fantasies are all sexual, Lester is really after Angela’s youth. He remembers being a hot, carefree teenager so fondly. Maybe if he can fuck a hot, carefree teenager again, he’ll be happy. He even pulls the ultimate crushing-teen move: he calls her, says nothing, and hangs up. Like the shower masturbation, it’s both pervy and sad. (You’ve all seen Manhattan, right?) He eavesdrops on Angela, who is intentionally grossing-out Jane by talking about how “sexy” Lester would be if he worked out and, mistaking it for actual attraction, he takes up running and weight-lifting. But he’s equally taken with another teenager, Ricky (Wes Bentley), his pot-dealing new neighbor. Inspired by Ricky’s no-fucks-given attitude, Lester does all the typical midlife crisis stuff: quits his job, turns his garage into a groovy hippie hangout, buys a red sports car.

Oh, also, Carolyn starts an affair with real estate hotshot Buddy Kane (Peter Gallagher) (“Fuck me, your majesty!). All the pieces are set in motion for a dark comedy about sex in the suburbs. There’s blackmail, extortion, taboo desire, and a Caroline/Natalie friendship so uneven I was practically screaming for Angela to get an Instagram so she can have all that validation she wants. But Ricky, and his family the Fittses, have moved in next door, bringing with them violence and melancholy that tip the scales of the movie toward drama.

They seem hopeless, like an inert, foregone conclusion. The mother (Allison Janney) is either drugged or brain-damaged, barely aware of her surroundings. When, at the end of the movie, she shows compassion for her son, who in turn asks her to take care of his father, I was sort of bewildered. There’s no love in that family, no “beauty,” no anything but boredom and despair. If the Burnhams are the typical American family at its worst, the Fittses are the worst American family, full stop. I can’t tell if I want them out of the story for artistic reasons or so I can pretend families like that don’t exist. There’s something repulsive in that house, and I can’t quite square the horror movie vibes from that half of the narrative with the rest of the movie.

Ricky Fitts is a budding filmmaker. Sort of a benign creep, he records Jane and her family through their windows and leaves a message for Jane in fire on her driveway, but when she tells him at school to stop filming her, he obliges and apologizes for scaring her. Ricky’s got a case of I’m A Weirdo-itis, but he isn’t dangerous, refusing to even defend himself when his abusive Marine Corps father (Chris Cooper) beats him up.

Ricky’s also responsible for the most iconic shot in the movie: the plastic bag. It’s the “most beautiful thing” he’s ever recorded: a plastic bag being blown around by the wind. He claims it was as if the bag were a dancing child. He says he felt a benevolent force in the universe when he saw it. He saw beauty in the world as a result of that bag. It is, to be perfectly clear, just a plastic bag. Like, there is a long shot in this movie in which we are watching the back of two people’s heads, and they are watching a TV, and on that TV is…a plastic bag. Drifting through the wind. Wanting to start again.

I get it! He’s a teenager! When you’re eighteen, you’re supposed to film street garbage and dead birds and find it all really meaningful. That’s what being eighteen is for. And the movie, thankfully, doesn’t ask us to have the same quasi-religious experience with this bag that Ricky did. He admits that the footage doesn’t capture what he felt, but it reminds him of it, like a souvenir from an important trip. Allow me to put my metaphorical cards on the figurative table, dear reader: I got absolutely nothing out of the plastic bag. I get what it represents, the same way I get what the red rose motif is about, but I just don’t…have any reaction to it.

Then again, I’m from a generation for whom it’s pretty common to record banality. I routinely see pictures of my friends’ outfits and meals, and if I want to remember an especially pretty sunset, I just snap a picture. We didn’t invent the idea of capturing the everyday stuff, but if I’d been an adult moviegoer twenty years ago, would I find windswept debris rapturous? Would I think Ricky a genius for recording it? Maybe. The movie won Best Picture. But come on…the meaning of life cannot possibly be found in literal litter. If @RickyFitts posted this shot to Instagram, I’m not sure I would even give it a like.

For the plastic bag—or really, for any of the somewhat forced coincidences that follow to make any sense—we have to be OK with the fact that these characters aren’t people but types of people. A Middle-Aged Man, A Wife, A Hot Girl, A Sad Girl, A Weird Kid. This is Anytown, USA, where everyone speaks in declarative sentences and aphorisms that neatly pay off later. To be successful, you have to project an image of success. Everything that’s meant to happen does. You have such hostility in you, Lester. I’m just an ordinary guy with nothing to lose. This is not how humans talk; this is how ideas talk. Like I said, the only way it makes sense is as a fable.

Come on…the meaning of life cannot possibly be found in literal litter. If @RickyFitts posted this plastic bag shot to Instagram, I’m not sure I would even give it a like.

A little time passes, and we’ve caught up to the intro: Ricky records Jane talking about her loser dad, then tells him she wasn’t serious about wanting him dead. But he’ll be dead soon, anyway, because here comes the return of Narrator Lester, with yet another considered aphorism: “Remember those posters that said today is the first day of the rest of your life? Well, that’s true of every day except one: The day you die.” (Allow me a quick aside to make my own related point: that phrase was popularized by a psychologist who later went on to found one of California’s most violent cults. Really. Look it up.)

It’s Lester’s Death Day, and time to reap all the little story seeds that have been sown. At Lester’s workplace, Mr. Smiley’s (ah, the search for happiness even penetrates the fast food market), he discovers his wife’s affair. Thanks to a series of misunderstandings, wacky coincidences, decontextualized footage, and a well-placed window, Colonel Fitts (Cooper) is certain that Lester is paying his son for sex, specifically gay sex, which the Colonel hates so, so much. And with her ego bruised from no longer being the more-desired friend now that Jane’s in a relationship, Angela is finally vulnerable enough to have sex with (be statutorily raped by) Lester.

Over the course of one fateful night, when it’s raining really, really hard because it has to be, we see Carolyn decide to shoot Lester dead…but she doesn’t. Lester could take Angela’s virginity…but he doesn’t (more on this in a second). The crimes we assume will take place do not, but Lester is still murdered…by the gay menace next door. No, not Jim! Or Jim! By Colonel Fitts! The repressed homosexual who hates in others what he hates about himself kisses Lester, can’t deal with the rejection, and so returns to shoot him in the back of the head as he’s staring at a picture of his family, realizing that actually, he has been happy during his adulthood. His life flashes before his eyes. Turns out, he goddamn loves the suburban lifestyle! He loved being a boy scout, he loved his grandma, he loves his daughter! He dies with a smile on his face, which Ricky copies, and for a brief moment this is almost the origin story for The Joker. Narrator Lester tells us that he has found the beauty in the universe. He tells us we do not understand it. But that we will someday, both a promise and a threat (we’re all gonna die!). And then “Because” by The Beatles plays, and the movie is over, and we are left wondering…because what?

Maybe there is beauty in the universe, but this mostly sad and slightly violent tale didn’t show it to me. The meaning is: the plastic bag. The answer is: you were happy all along. These conclusions seem hollow. I wonder what the movie would be like without the narration, if it were just a story from which I was allowed to draw my own conclusions without being told what it was all about. And anyway, I already knew it’s the little things that make life worth living, because I’ve seen “Our Town (you know what’s sometimes mocked but is actually really goddamn good? Our Town!).

I can’t totally dismiss American Beauty. It gives you a lot—perhaps even too much—to think about. But then you overthink, and you rethink, and ultimately, I’m not sure what’s there. There are messages and ideas and no easy answer but a too-neat ending. It’s like a Greek tragedy except, well, I don’t find Lester’s death all that tragic. He’s a grown man who wants to fuck a teenager, but instead he’s murdered. Does it make me shallow to be OK with that?

Which brings us to the fact that Kevin Spacey is in this movie, and we know now that around the time he was making it, has was also forcing himself on teen boys. And that Thora Birch, briefly topless, was seventeen when she filmed this. And the the only reason Lester doesn’t have sex with Angela is because she tells him she’s a virgin. It’s presented like a wake-up moment: he finally realizes that her youth is hers to experience, not his for the taking. But it’s also an especially disgusting kind of sexual logic. If she’d been less pure, if she’d been more experienced, it would have been OK to go through with it? Virgin or not, she’s your daughter’s best friend, my dude!

Angela, for her part, might be lying to everyone else about her level of sexual experience, but she seems to know the truth about the industry (modeling) she wants to break into. She says she’d be willing to have sex with a photographer for the sake of her career, and I believe her. After all, she’s willing to have sex with Lester for the sake of feeling good about her looks (I will note, though, that this is very different from her “wanting it” or “coming onto him;” she’s clearly nervous and uncomfortable. She doesn’t seduce him in the slightest; it’s all for show). Trading sex for fame, getting young girls into bed (or couch), filming your girlfriend without her consent, then with her consent. And Kevin Spacey, a talented creep in the middle of all of it.

Re-watching American Beauty, I was struck by how right it all was, how it took these serious issues seriously, and presented them in a complicated way, not laying into tawdriness. And then I was disappointed. If we knew all of this back then, if we understood that flirty teens are just showing off for their friends and don’t actually want to fuck adults, then how come we let it go on so long? How did twenty years pass and we’re only just now saying, wait, maybe Kevin Spacey shouldn’t be famous, and maybe we should give Mena Suvari a little credit? It was twenty years ago. I really can’t stress that enough. It was 1999. FL