At first, it wasn’t considered music. Then it was just a fad. Later, it became too dangerous. Corporations wilted under pressure, refusing to do business with it. It was also deemed a security risk, a liability when booking concerts.

Today, almost all of that tarnish has been washed away by unyielding waves of success, as rap music and hip-hop culture came together to form one of the most significant cultural movements of the last fifty years. The creative juggernaut was created in the 1970s, enjoyed a sustained creative explosion in the ’80s, emerged as a scapegoat and bestseller in the ’90s, dominated the pop culture discourse in the ’00s, and became fully integrated into mainstream society and widely accepted as the definitive driving force of pop culture by the ’10s.

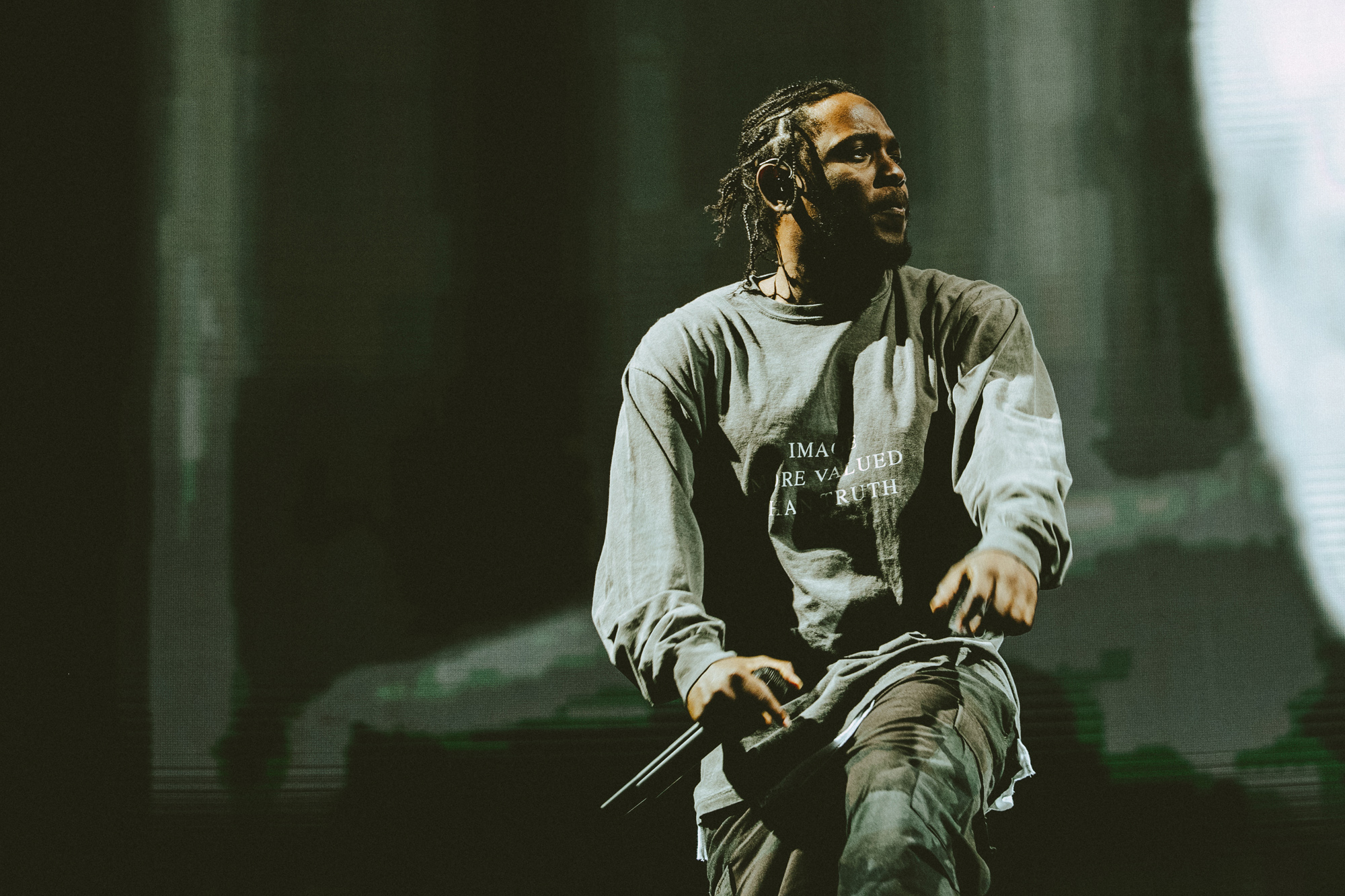

This decade kicked off in grand fashion, ushering in the major label debuts from Drake and Nicki Minaj in 2010, two entertainers whose shine remains bright today. Those projects, plus 2011 and 2012 releases from JAY-Z and Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, A$AP Rocky, ScHoolboy Q, Future, and Meek Mill, foreshadowed who (and what type of artist) would reign throughout the rest of the decade. But there are other, larger milestones to consider besides major rap album releases, which have routinely debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard charts since 1991.

In 1989, rap’s first Grammy Award was bestowed upon DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince for “Parents Just Don’t Understand.” The rap cognoscenti boycotted the milestone event because it wasn’t included in the televised portion of the broadcast. The rap community was also upset, as the award went to a “pop” incarnation of the genre, one that was PG-rated and didn’t represent or reflect the cutting-edge work taking place at the core of the music.

In 1989, rap’s first Grammy Award was bestowed upon DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince for “Parents Just Don’t Understand.”

Fast forward to 2012. Rap icon LL Cool J began a five-year run as the host of the Grammys. During his tenure, rap had become so accepted by gatekeepers that Kendrick Lamar earned eleven nominations for his 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly. When the revered collection lost to Taylor Swift’s 1989, the fallout was massive, delivering the standard racial bias claims, but also featuring commentators who claimed Lamar’s effort should have won because his was a better piece of art than Swift’s. That’s a seismic shift in how rap was perceived by music industry gatekeepers, who were now having a rapper hold court on their awards and acknowledging one of rap’s most respected artists as creating one of music’s best albums of the year.

Lamar also had a hand in yet another pivotal music shift regarding how genres are consumed and discussed. In August 2013, Big Sean released his single “Control” online, which also featured appearances from Jay Electronica and Kendrick. Hundreds of songs had been released online prior to “Control,” but this one became the talk of social media thanks to K.Dot’s assertion that he was “trying to murder” A-list rappers Drake, J. Cole, and Wale.

For context, by 2013, rap had largely gotten away from being the contact sport it had been in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, when confrontational words in song often led to physical confrontations in real life. Sure, Kendrick Lamar said he tried to lyrically murder those artists, but the audacity and fervor with which he made the statement set the internet ablaze, demonstrating that rap remained as competitive as ever, with bragging rights for the title of Best Rapper Alive still something even the younger generation was obsessed with.

One of Lamar’s mentors, Dr. Dre, made his own news throughout ’10s. In 2014, the Beats Electronics company he co-founded with record industry titan Jimmy Iovine was sold to Apple for $3 billion. It remains the biggest deal for a company owned by a rapper, and showed that Dr. Dre’s dominance in rap—which had begun in the ’80s through his work with J.J. Fad, Eazy-E, and N.W.A.—showed no signs of ending.

Dr. Dre rose to acclaim as a member of N.W.A. and the 2015 biopic on the group, Straight Outta Compton, grossed more than $200 million worldwide at the box office. At the time, it was the highest-grossing film by a black director (F. Gary Gray). In addition to its commercial success, the film was nominated for an Oscar (Best Writing, Original Screenplay) and won twenty-eight awards, including the AFI Award for Movie of the Year, MTV Movie Award for True Story, and two NAACP Image Awards. Compton was not just a revered rap film, it was a revered film.

As a tale of rappers from the gang-infested streets of Compton, California, became one of 2015’s biggest successes at the box office, rap found its way into the hallowed halls of the Smithsonian. Its National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) made hip-hop one of the cornerstones of the inaugural Music Crossroads exhibition, which aimed to tell the story of African American music from its inception to the present. Rap was now considered an integral part of the artistic evolution of U.S. music.

Then, Nielsen Music’s 2017 year-end report revealed that R&B/hip-hop was the biggest music genre in the U.S., at least in terms of total consumption. Eight of the ten most-listened-to artists of the year were R&B or hip-hop acts, and disproving those who felt the genre was losing creative or commercial steam, rap had a 25 percent growth in consumption in 2017 as compared to 2016. That uptick was, in part, thanks to the success of releases from relative newcomers such as Kendrick, Vince Staples, Drake, Joey Bada$$, Migos, and 21 Savage, as well as veterans like JAY-Z, Gucci Mane, and Big Boi. Rap turnover remained as robust as ever, but more and more artists were showing staying power, whether they emerged in earnest in the ’90s (JAY-Z), 2000s (Gucci Mane), or 2010s (Drake, et al.).

By the 2010s, rap was finally on the world’s biggest stages, despite having been virtually unbookable for anything other than club dates in the ’80s and ’90s over concerns about violence and low ticket sales.

By the 2010s, rap was finally on the world’s biggest stages, despite having been virtually unbookable for anything other than club dates in the ’80s and ’90s over concerns about violence and low ticket sales. It wasn’t until the success of The Hard Knock Life Tour with JAY-Z, DMX, Redman, and Method Man in 1999 and the Up In Smoke Tour with Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, and Eminem the following year that rappers became a safe and reliable draw at larger venues. Now, virtually every festival of note in the 2010s was anchored by a rap act.

It was telling, too, when Hollywood heavyweights Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom Hardy made a reference to Bobby Shmurda while promoting their 2015 film The Revenant. Set in the uncharted North American wilderness in 1823, the film had nothing to do with rap, as of course the genre wasn’t conceived for another one hundred and fifty years. And yet, it was another example of rap infiltrating our country’s subconscious. Two superstars joking about including a lyric from a popular rapper in a movie set in the 1800s. Whether it be in The Revenant or the 2015 musical Hamilton—an imaginative look at one of our founding fathers that notably includes both singing and rapping—hip-hop and rap have clearly stood the test of time. FL