By all rights, this is a story Vince Gilligan—co-creator and writer behind epic, Southwest-based mysteries like The X Files and Breaking Bad—could sink his teeth into, rich as it is with the narrative of odd-yet-believable U.F.O. references, craggy, windswept deserts, and lost souls. But the tale of Jim Sullivan, a Malibu-based singer-songwriter and guitarist who released two opulently arranged albums with little fanfare (at the time) before disappearing without a trace in New Mexico in 1975 is altogether too real.

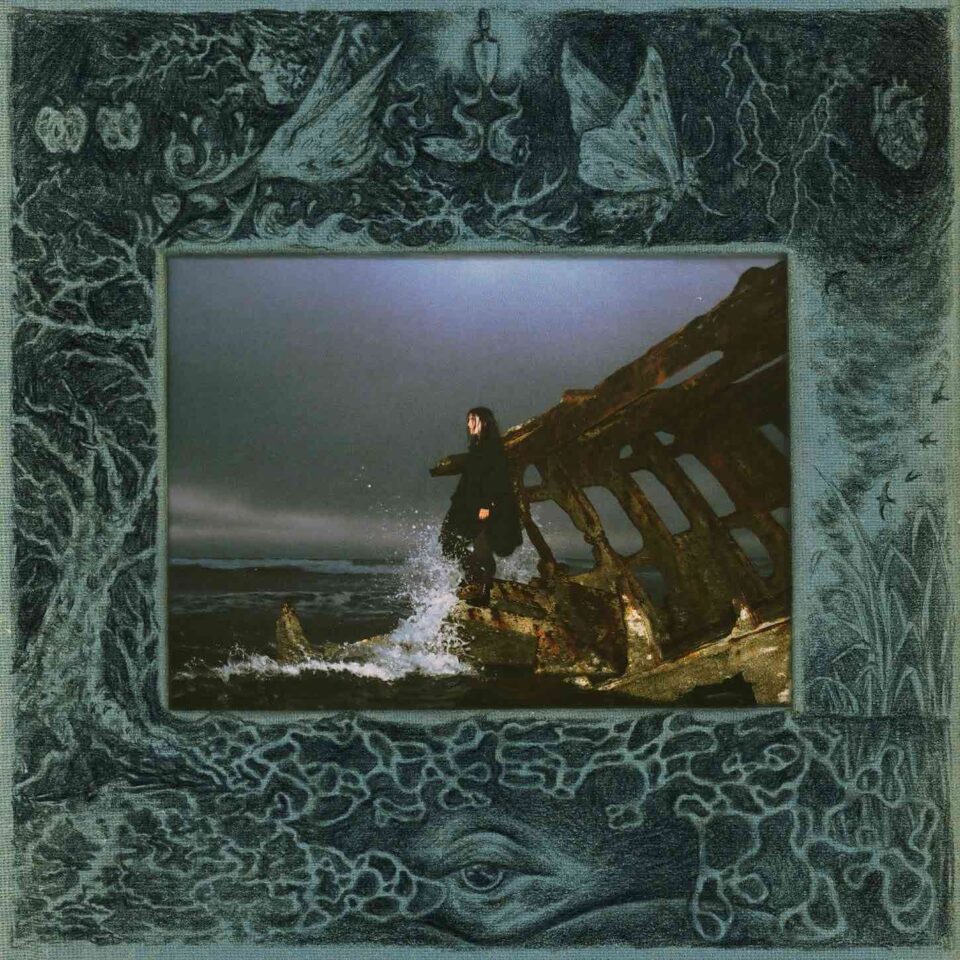

On his way to Nashville, alone in a Volkswagen Beetle, Sullivan checked into a motel in Santa Rosa, bought a bottle of vodka, abandoned his vehicle, and was reportedly last seen walking away from his Bug. Sullivan’s guitar, cash, clothing, and a crate of his albums—1969’s U.F.O. and his self-titled 1972 effort, both reminiscent of the Tims, Hardin and Buckley—were found at the scene of his last known whereabouts.

“After the facts, no, we heard absolutely nothing about what happened to my dad,” says Chris Sullivan, the songwriter’s son and a professor at San Diego’s Mesa College, of what happened to his father forty-five years ago. “Our families were out there for a time—they were bulldogs—even tried to get people to fess up, but nothing ever came of it… I’ve had a long time to think about all this.”

missing person article from Santa Rosa News, April 10, 1975

While no answers have been found as to what happened to Sullivan’s person—murdered by federales or bandits or transported to another universe by his treasured alien wildlife?—it is his soul’s soundtrack that was left behind: the smartly lyrical, lushly produced likes of U.F.O., Jim Sullivan, and a rare collection of previously unreleased demos If the Evening Were Dawn. All are in the good hands of the label Light in the Attic, who are currently overseeing Sullivan’s recorded output.

Chris Sullivan recalls getting his love of music from his parents, one a struggling artist and the other—his mother, Barbara, who passed away in 2016—an employee at Hollywood’s Capitol Records. “There was music in my house eighteen hours a day back then, probably,” he recalls. “Dad’s relentless attempts to make it in the business which occupied much of the psychic energy of the house” made Jim Sullivan’s albums difficult for son Chris—thirteen when his dad went missing—to hear at the time. “I was probably sick of them because of that,” he admits. “Now, though, I think they’re pretty good. U.F.O., in particular, because it’s got such a great sound quality to it.”

The second album, Jim Sullivan, (or, as Chris calls it, “the Playboy LP,” as Hugh Hefner’s very own, short-lived label of the ’70s released it), is something that he’s just getting around to listening to and liking, “as, at the time of its release, it was a pretty fraught moment in our family’s history. I did some sublimating at the time to avoid it. Now, it sounds pretty good, especially songs such as “Amos,” with really great, vaguely abstract lyrics and jazzy Wrecking Crew backing.”

Whether it be these two albums or the records of demos and unreleased tracks that is If the Evening Were Dawn, Chris Sullivan is happy about one thing. “I never could have predicted this,” says Sullivan. “If you told me that Jim Sullivan’s original records would be sought after as collectors’ items, and that a record company would want to re-issue them, I would have been like ‘Yeah, right. Never.’”

What sort of guy—beyond being driven enough to leave wife, child, home, and familiar surroundings for the possibility of Nashville success—was Jim Sullivan? And in that knowledge, are there any clues as to what became of him? “Clearly you don’t pack up everything and move from your sleepy little hometown and move to the big city as he did when he moved to Los Angeles without thinking you have a shot… Then leave again when you’re looking for another shot,” said his son.

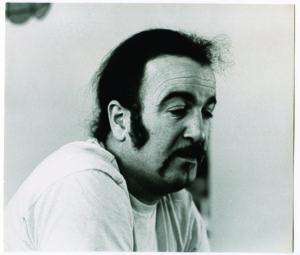

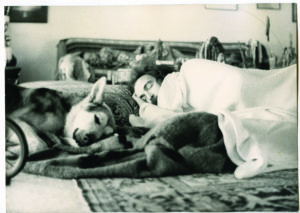

According to Chris, his Dad was a guy who was “super charismatic, super gregarious, super magnetic…people were just drawn to him. My wife tells me that I am flypaper for freaks. I guess a little of that from him rubbed off on me, because he just had that shiny energy. He was attractive in that way.”

Chris remembers the wild times of people always in-and-out of the Sullivan house, partying, and thinking that was what being an adult would be like.

“It was odd that all of his stuff was left behind. If you were killed or disposed of, would someone not get rid of all of the evidence? Maybe he just took a long walk? Maybe the grind of trying to make it in an industry he loved so much—and failed at, for lack of a better word—just got to him.” —Chris Sullivan

One thing that both parents shared was a belief in the extra-terrestrial life forms of which Jim Sullivan wrote and sang. “For sure, they both fully believed that there was life out there,” says Chris. “U.F.O.’s were part of his life, and my mom’s too. They were both born during the Depression, raised in pretty Catholic, dogmatic families, came of age at a time of exploration—a classic ’60s trajectory. The whole trip. Plus, my dad was a mystical guy. And you could put air quotes around ‘mystical,’ if you like.”

Something that comes through loud and clear in a short Light in the Attic documentary on the subject is that Barbara Sullivan believed her husband’s disappearance could very well have to do with an alien abduction. “She was a pretty free-thinking person…that there was a multi-dimensional realm we all could occupy, and that eventually, they could occupy that realm together,” Chris says with a laugh. “Hell, why not?”

U.F.O.’s aside, Chris Sullivan says he’s thought a great deal about his father’s disappearance over the course of his life, but has no clear theory as to what happened. “I think he got on the wrong side of someone out there and was probably murdered or buried… He was stopped by the police out there, and law enforcement has a way with making people disappear. It was odd, of course, that all of his stuff was left behind. If you were killed or disposed of, would someone not get rid of all of the evidence? Maybe he just took a long walk? Maybe the grind of trying to make it in an industry he loved so much—and failed at, for lack of a better word—just got to him. Maybe I have some mysticism to me as well, tempered with pragmatism that overwhelms me. Perhaps he just walked into the desert. The mystery of it all is just nagging…a long way to say that I have no idea.”

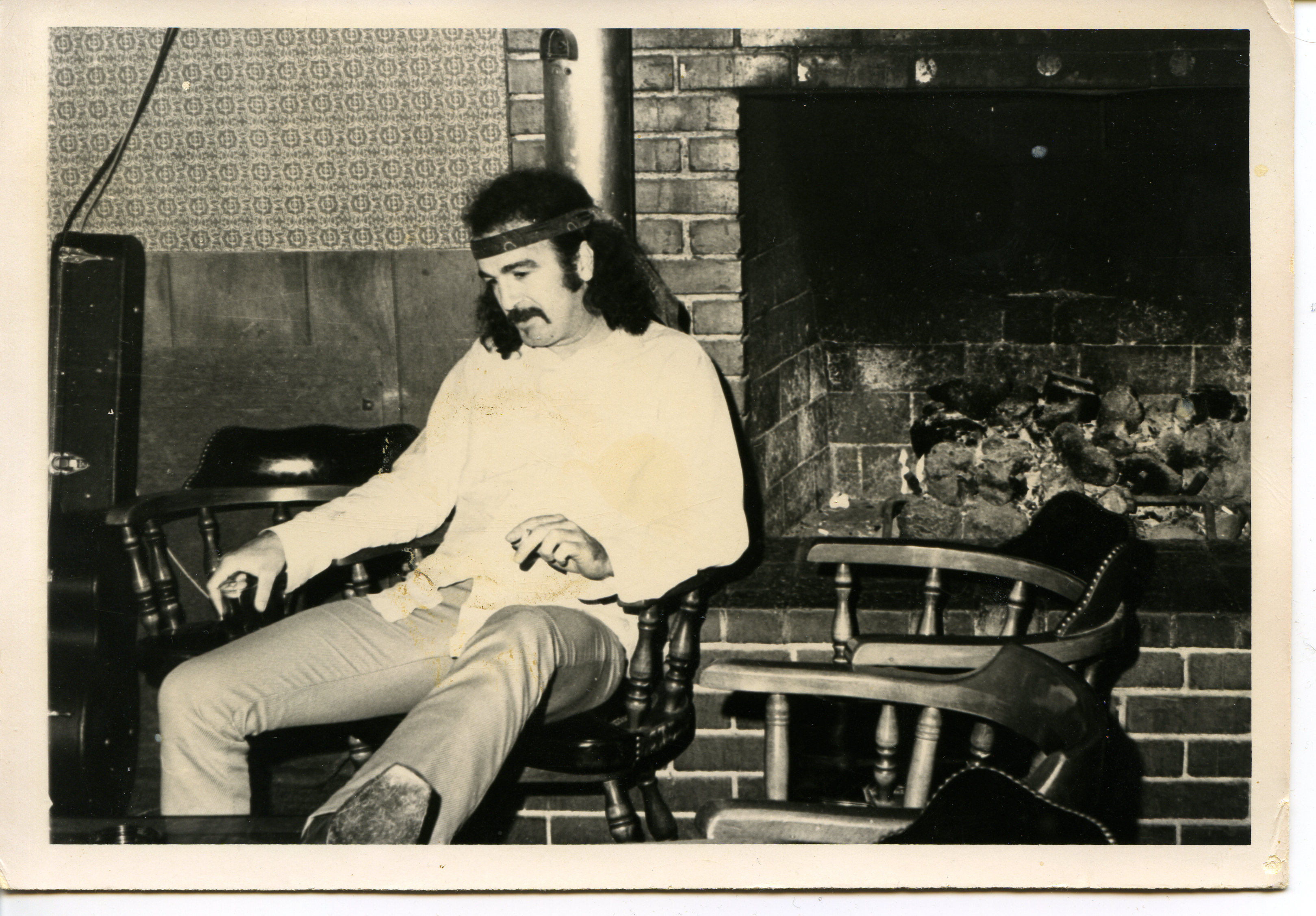

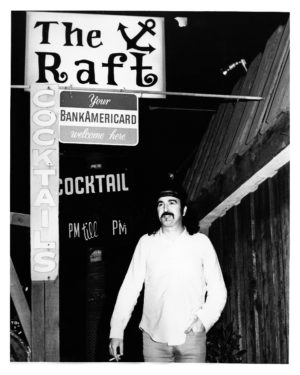

Producer Al Dobbs, a gregarious man who talks easily about the good times of the 1960s and ’70s (“Jim drank too much, but we all did. We were a partying crowd, what can I say?”) had all sorts of faith in Sullivan and his talents—so much so that after hanging at the Raft club in Malibu, and hearing the singer-songwriter’s poignant, hearty sense of songcraft, he put up his own money and created his own small record label, Monnie, to release U.F.O.

“Hell, no one was going to do it, and man, Jim certainly went to everyone to try to get a major label deal—including Capitol, where his wife Barbara worked,” Dobbs says. “I look back on it now and that was crazy, starting my own label. But, I believed in him.”

Dobbs recalls the easier to live in, less expensive Los Angeles of the time—both he and the Sullivans lived in Sherman Oaks—and the nightly drives from production gigs at NBC’s Studios for Laugh-In or The Steve Allen Show to Malibu and The Raft. “You can’t make that drive now,” Dobbs laughs.

Once at The Raft, Dobbs saw and heard a songwriter whose stories were unique in their honesty. “See, I actually think that he believed in the U.F.O. Jim was speaking from his heart. And quite frankly, in those days, there was no one talking about that. Now, there’s series on ancient aliens and discoveries. Not then. Just him,” Dobbs says.

photo courtesy of Jim Sullivan Estate

Dobbs and burgeoning legendary bassist Jim Hughart would hang out at The Raft, (“much wine was shared between us”), and both fell in love with Sullivan’s style; then the former had an idea to record Sullivan. “I had no experience doing that, either,” he says. “I went out and bought an Ampex reel-to-reel recorder, just to learn how to use one.” Dobbs also played novice photographer and album cover artist when he shot Sullivan alone on the beach during a group campout. “We had to clear our ears every five minutes because of the sand and the wind, but that was our scene. We didn’t hang out at the LA clubs. We were Malibu guys. The cats from the Wrecking Crew who played on Jim’s album—they read music like it was a racing form. And they liked Jim. They dug him as a person, a player, and as a songwriter.”

For Al Dobbs, the blessing behind the “whole thing of re-releasing Jim’s work” is how it brought so many of his past Malibu associates and friends back together again.

“Jim certainly went to everyone to try to get a major label deal—including Capitol, where his wife worked. I look back on it now and that was crazy, starting my own label. But, I believed in him.” —Al Dobbs

“I knew Chris when he was seven years old,” Dobbs explains. “Barbara passed, but it was nice seeing her before that. She was the glue that held this all together: a good wife, a dear friend, and an excellent cook—the Thanksgiving dinners we had at their house, to say nothing of the constant partying, that was something. She was a dear lady, and she was thrilled to see these records out again. We all are thrilled, but mostly her; she always had faith that at some point in time, there were going to be people who would listen to and finally appreciate her husband’s music. There are people who will never know Jim, but after all this time what we thought was good, turns out to be good—that this guy turned out to be a lyricist and composer who said something, someone of real merit and worth. That’s satisfaction.”

One thing Chris Sullivan wants people to know about his dad? He was a good guy and a talented musicians. “Some of that ability gets lost in the mix of such a fascinating story,” Chris says. “He was really great at what he did.” FL