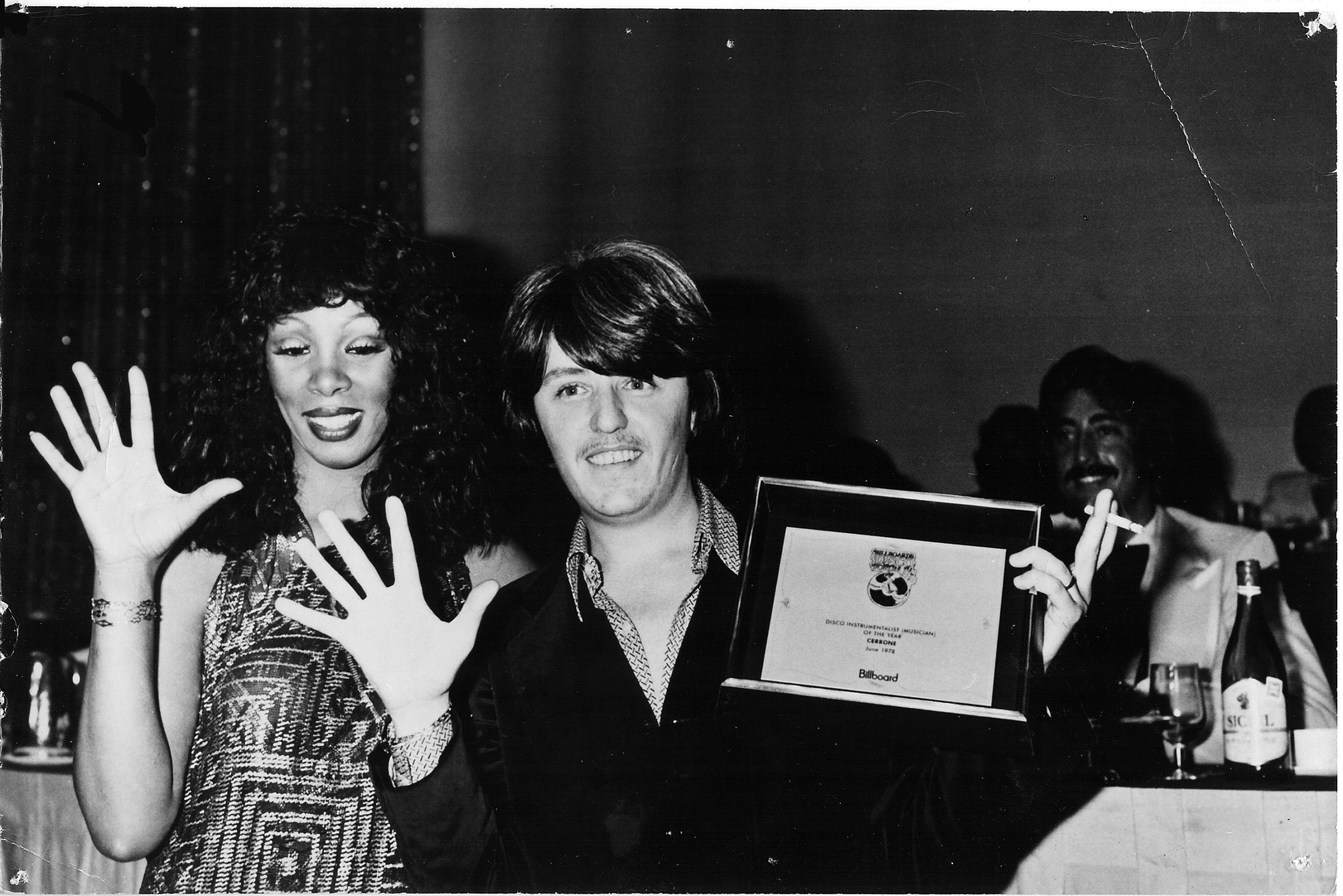

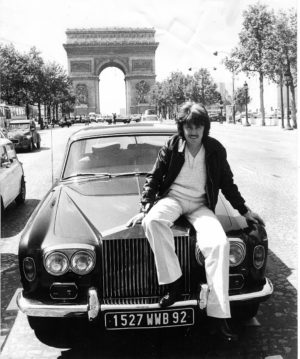

Marc Cerrone—better known just as Cerrone, the ’70s and ’80s disco era’s most thought-provoking Franco-Italian drummer, composer, and producer—isn’t done making you think, or making you dance.

The artist known for the environmentally sound super hit “Supernature” (among others, such as the sensual “Love in C Minor”), was a stalwart amid music’s most decadently sleek era, during which there was always something raw in the mood and something suitably primal in his rhythms.

Now back to making electronic dance music that inspires crowds to action beyond just taking E, the theme of his new all-instrumental album DNA is making the earth a better place.

DNA is a return to deep electronic music after the live instrument–heavy Afrobeat and hip-hop laden Afro EP and your Red Lips LP of 2016. Why go back to the laptop?

I think this is the result of having been into DJing for six years now. I’ve performed live concerts throughout my career, but because my record company pushed me to try DJing, I enjoyed this new approach. This also allowed me to take part in festivals I could not do otherwise. In my DJ sets, I only play my own repertoire. This is the reason why I had to look for some tracks I never performed live, and obviously most of these were from my early “electro” period, albums like Supernature and the Brigade Mondaine soundtrack. Also, the audience would prefer the original versions to the remixes, which left me some room to add short transitions between tracks to tie the set together. Little by little, I realized these sketches, these little tracks were the starting point to new album tracks. And it’s much easier to create electronic music this way. In fact, DNA was somehow born on stage while mixing as a DJ.

What do you see in the electronic dance music scene now that you didn’t see at your start?

I think there is lots of good music to listen to nowadays, but to be frank, nothing has ever surprised me as much as the creativity of the bands back then in the ’70s, such as Kraftwerk, Rockets, Tangerine Dream… Today is much more about the production than the creativity, in my humble opinion.

As someone who started as a live drummer, how do you approach all aspects of sound now—from composition to production?

I won’t surprise you by telling you that rhythm is essential [laughs]. Back in the old days, I used to lay my drums first—with the help of a click track—and then all the other musicians would come add their part in the multitrack recorder. Today is no exception. I use Roland V-Drums, which are excellent MIDI drums; I lay the rhythmic track in my Logic Pro with it. Thanks to MIDI I can easily change the drum’s sounds for optimal results, and just as in the old days, I don’t quantize the whole track; instead, all of the different elements are quantized relatively to the drums, to keep that groove. That’s the secret.

You are credited with de-tethering the kick drum from the rest of the percussive miking, allowing for greater emphasis on that first beat. You’re probably the first drummer to initiate the classic dance beat: 4/4 on the kick, 2/4 on the snares and eighth notes on the hi-hats—laying the groundwork for house and techno. Can you speak to that process?

Before starting my solo career, I was drummer in the band Kongas, whose music was in the afro-rock style. In this band there were two percussionists who could go on a percs solo for say, ten to fifteen minutes. And I would back them up with this basic 4/4 rhythm which had already proven at the time this efficiency for the audience. So, when I started my solo career while recording Love in C Minor, this was something I had in mind, for it was just an unbeatably efficient rhythm. It’s quite crazy knowing how many bands and musicians have used similar patterns ever since.

The then-fresh technology of electronic music is what made albums like Supernature… super. How did you take to technology?

“Disco was much more than a simple style; it was a mood, it had a soul, it was a way of life. Celebration, joy, and dance.”

Actually, it all started by some fluke, when we were delivered an ARP Odyssey synthesizer in the studio. It was something really new, it even took me some time before I could make the damn thing work! Eventually, one of the first sounds I came out with was the famous Supernature sequence, because I couldn’t figure out how to deactivate the auto-repeat mode. But little by little the synthesizer became an essential and versatile tool to make nice basses, get strange sounds, or make great solos—and definitely a keystone for my music.

I know you have always been devoted to issues of climate change and environmentalism, but back in the day, those things weren’t considered as necessary as they are today. Was there backlash?

The most incredible thing about this is to see, forty-three years after the release of Supernature, that sadly, many of the things we could fear back then are happening now… But the good thing is to see that since then, the awareness of environmental issues has spread worldwide. Therefore, I cannot find more wise and accurate words than the ones Jane Goodall said, and let me use, in my single “The Impact”: “Every single day, we make some impact on the planet. We haven’t inherited this planet from our parents, we’ve borrowed it from our children. If we get together, then we can start to heal some of the scars that we’ve inflicted.”

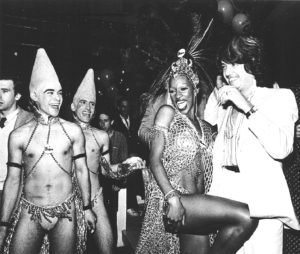

When “disco” became a dirty word, what was your first reaction? What did and does disco still mean to you?

In fact, when the “disco sucks” movement started, I did agree with it a bit because to me, turning pop songs into fancy disco tracks, which were to be performed by the major pop stars who actually had no clue what it was all about, was nonsense. Disco was much more than a simple style; it was a mood, it had a soul, it was a way of life. Celebration, joy, and dance.

I know you were partially influenced to make music after seeing a Jimi Hendrix live show, but acts from Barry White to Chicago were also important to you coming up, right?

When I was recording Love in C Minor, my first solo album, it was much more a way of capturing my musical experience. Therefore, I did not have any concessions regarding song or radio format. Mind you, the A-side track was nearly seventeen minutes long! As I made this record essentially to please myself by putting in it all my influences—Barry White–like strings, Chicago-like brass, etc.—I didn’t think it could sell much more than a few dozen copies.

You once said that, increasingly, music has too many words and lyrics. How much of that had to do with making DNA an all instrumental album?

As I mentioned earlier about the “disco sucks” thing, too many vocals is something that always turns a track into a plain pop song; and you get away from the real spirit of disco.

Do you feel as if you want to keep making new music, beyond DJing and live events?

How could I experience anything else but pleasure, joy, and pride when I have spent nearly fifty years of my career seeing new generations joining the movement and making it last? There were several periods—starting with the ’80s and ’90s with the first remixes, the first samples from the year, until the 2000s—where the DJs pushed dance music in the front again. And now, what’s most incredible is that I have become a DJ myself in front of an audience which still has an average age of eighteen to thirty-five, and sometimes older than that. They know almost every track. A great energy that helped to create DNA will make me work on more music, there’s no question about it. FL