I’ve always admired songwriters who show the inherent fallibility of humans, peeling back their exteriors and revealing the lizard brains underneath.

I love to study the dings, chips, and scorch marks of their lives and how that has informed their art. It’s far more edifying than marveling under the lights of industry artifice while viewing each white marble facade. One of my favorites is Neil Young, who suffered from polio, back pains, epilepsy, and a brain aneurysm in 2000. Another one, from the independent rock canon, is XTC’s Andy Partridge—he infamously pulled the plug on performing with his fellow Swindon rockers after a San Diego gig for the classic English Settlement tour in 1982 after panic attacks and stomach cramps assailed him on stage. XTC subsequently released some of their best albums in the ’80s purely from the studio, without any traditional touring supporting the releases.

Another favorite post-millennial rocker with plenty of acknowledged flaws is Radiohead’s Thom Yorke. He was born with a paralyzed left eye, something I immediately connected with since I saw asymmetry in my own face with a lazy left eye. He took his drooping eyelid from a botched surgery and wore it as a badge of honor on stages across the world.

Thom Yorke always impressed me as a gangly kid growing up in the small rural town Loomis, California. I lived on five acres and we owned pygmy goats, a horse, a pony, and chickens for pets. Listening to a band from a larger city reminded me that living in a place with a larger population can be just as isolating.

I retreated to music and video games as a teenager. Radiohead’s The Bends was the second CD I bought with my own money at a Dimple Records (RIP) in Roseville, CA. The first compact disc I grabbed for Christmas at that same shop on Douglas Blvd. was (What’s the Story) Morning Glory by the working class Britpop lads Oasis. Radiohead always seemed like the working class boys from the dark future after The Bends came out in March of 1995. I came to it in the fall, as the oak trees in Loomis turned skeletal.

The Bends was different. The chem trails of grunge were still raining down on us. It sounds like a panic-addled diary typed out on a computer screen. It demands your attention and killed Radiohead’s early “Britpop” labels. It was everything for a middle schooler. I was grateful for my musical iron lung. The Bends holds up after twenty-five years.

Radiohead was determined not to be just another Britpop or grunge group. The Bends was their first line of code to fill up an ominous blank screen after 1993’s Pablo Honey and the runaway “Creep” single that haunted them. Radiohead’s black mirror needed something colorful and brash to help them from falling into an endless abyss of narcissism and anxiety. The Bends filled that need.

Upon revisiting the record, I’ve ranked The Bends’ twelve tracks according to how well they’ve held up.

12) “Sulk”

“Sometimes you sulk / sometimes you burn / God rest your soul / When the loving comes and we’ve already gone / Just like your dad, you’ll never change.”

“Sulk” taps into Yorke’s early fascination with violent news headlines. The careening stadium rock song was inspired by a killing spree by a solitary shooter in Hungerford, England in 1987. As a teenager, I naturally glommed onto the defeatist lyrics above. They exalt the physical act of sulking into some type of odd narrative of a superhero battling themselves. Although this track is sitting in the basement of my personal ranking for The Bends, it epitomizes the internal wrestling between Britpop histrionics and post-rock composure that Radiohead embodied before diving headlong into studio experimentalism on future records. Trivia note: Yorke self-edited the concluding lyric “just shoot your gun” when “Sulk” was recorded in late 1994, since Kurt Cobain’s death was still casting a long shadow in the music world. He didn’t want anyone to mistake the lyrics as being about the late Nirvana leader.

11) “Bones”

“I don’t want to be crippled and cracked / Shoulders, wrists, knees, and back / Ground to dust and ash / Crawling on all fours.”

Yorke has a lot of songs that highlight an almost unhealthy obsession with being incapacitated during this period in his life, as he inched closer to his thirties. Though he seems almost jovial in interviews these days after having children, “Bones” is the high watermark example of the old Thom. I listened to this song a lot when I was laid up last summer after breaking my left ankle ice skating. It’s a good song when you just feel deflated and want to connect with the raw energy of running away from our deepest fears: death and dismemberment. The lyrics always reminded me of Lot’s wife, when she turned into a pillar of salt after looking back at Sodom. That was always a stark image in my mind. Yorke might just be talking about the physical toll of touring, but he relays the sentiment at an almost Biblical scale.

10) “High and Dry”

“Drying up in conversation / You’ll be the one who cannot talk / All your insides fall to pieces / You just sit there wishing you could still make love.”

In a 2013 interview with The Guardian, Yorke remembered his journey as a songwriter: “To begin with, writing songs was my way of dealing with shit. Early on it was all, ‘come inside my head and look at me.’ But that sort of thing doesn’t seem appropriate now. Tortured often seems the only way to do things early on, but that in itself becomes tired. By the time we were doing Kid A [their fourth album, released in 2000] I didn’t feel I was writing about myself at all. I was chopping up lines and pulling them out of a hat. They were emotional, but they weren’t anything to do with me.”

This song makes a good first impression solely from the vocal performance. “High and Dry,” which is a remix of an original demo from the Pablo Honey days, is often cheekily dedicated by Yorke to “older people, who don’t like loud music.” I’ve always been an old soul.

9) “Bullet Proof…I Wish I Was”

“Wax me, mold me / Heat the pins and stab them in / You have turned me into this.”

Critics looking to psychoanalyze Thom Yorke’s depressive moods were initially attracted to this song’s tone of desperation like bugs to a porchlight. An acoustic version of “Bullet Proof” is an excellent companion piece to the “Fake Plastic Trees” single. It’s also beautiful, even without the guitar noise from Jonny Greenwood and Ed O’Brien. “Bullet Proof” resonated with me more during college after romantic heartbreaks, or times of yearning for romance. The gaping valleys surrounding the ellipsis in the middle of the track title in particular is tailormade for the text messaging age, when there are no words to communicate your knotted ball of feelings for the opposite sex. Periods become bullets in this track, and Radiohead knows how to drift within the spaces.

8) “Fake Plastic Trees”

“She looks like the real thing / She tastes like the real thing / My fake plastic love.”

You can get cheap and downplay the importance of “Fake Plastic Trees.” It’s a widely popular Radiohead song, after all. Sure, it may have been everywhere in the late ’90s and 2000s, a go-to school talent show staple for teenagers learning to play guitar. Remember when Thom Yorke had bleached blond hair? All of that doesn’t discount it being an incredible earworm that builds on itself like a musical Jacob’s Ladder. According to rock lore, Yorke went back to the studio after the band went to a Jeff Buckley concert and recorded the vocals in two takes. He then broke down and cried. “Fake Plastic Trees” casts a dirty light on the crass world of mass marketing and consumption. I’ve always loved the slow buildup as it grows from an acoustic dirge to a fully orchestrated menace.

7) “Black Star”

“Blame it on the black star / Blame it on the falling sky / Blame it on the satellite that beams me home.”

Jonny Greenwood’s influence becomes readily apparent on this track. R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe took Thom Yorke under his wing when the band toured with Radiohead and Alanis Morisette and gave him a bit of advice about life in the public eye. The R.E.M. guitar jangle from Greenwood presages that early career connection between the bands, and is downright infectious. The Bends also saw the momentous entrance of Nigel Godrich’s influence, the band’s longtime producer and de facto sixth member. He engineered The Bends and produced “Black Star.” This is the beginning of a longtime partnership that was only just starting up between the core group and Godrich. I’ve often inserted “Black Star” into my morning commute playlists—it had a hazy wake-up vibe, and I later discovered that Yorke joked that the song is about “getting back at 7 o’clock in the morning and gettin’ sexy.” I thought it was the most nihilistic song on the album. Go figure.

6) “(Nice Dream)”

“I call up my friend, the good angel / But she’s out with her answerphone / She says that she’d love to come out but / The sea would electrocute us all.”

The swirling atmosphere for “(Nice Dream)” paves the way for Radiohead songs from the Kid A and Amnesiac era. In a Matrix-like swap, the imaginary world turns into just a “nice dream” here, as the scales on the listeners’ eyes fall off. It smacks of the current online world, putting up a facade via TikTok or Instagram stories, when the reality is not nearly so rosy. I often listened to this song in high school in the wake of discovering my mom had breast cancer, and again on long rides back from college. She’s thankfully a survivor of that devastating illness, but in the middle of her treatments I found solitude in realizing that even when reality hits with an electric jolt, we can be strong enough to persevere, especially with family by our side.

5) “Just”

“Don’t get my sympathy / Hanging out the 15th floor / You’ve changed the locks three times / He still comes reeling through the door.”

“Just” always reminds me of someone in grade school who desperately wanted to be friends with me. His name was Brad. At first I was like Yorke and tried to elude him, but I eventually learned he was just a lonely guy without a strong family life. I often think of him and how he was bullied a lot in middle school.

Greenwood’s guitar playing is at its most intricate and commanding here, showing his love for the ever-ascending octatonic scale. Yorke challenged Greenwood in the studio to put as many chords into a song as possible, and this is the result. The music video for “Just” always fascinated me too, especially its cliffhanger ending where the camera zooms in on a middle-aged man’s mouth as he lies down in the middle of the road. What he ultimately says is up to the viewer, since the subtitles abruptly drop out.

4) “Planet Telex”

“You can force it but it will stay stung / You can crush it as dry as a bone / You can walk it home straight from school / You can kiss, you can break all the rules.”

This is one of my favorite opening tracks for a rock record. It starts with the buzzing surge of the Roland Space Echo and reverb-heavy piano chords, and quickly veers into the shoegaze rock lane more than any other track on The Bends. I would often listen to this on repeat in my Ford Focus—it kickstarts the album so damn well. It’s a daydreaming song for sure, and helped define Radiohead’s purpose on the record and shake off early naysayers.

3) “The Bends”

“Where do we go from here? The planet is a gunboat in a sea of fear / And where are you?”

If you would have asked me to rank The Bends’ songs twenty-five years ago when I first listened to it, I would have easily put the title track at the top of my list. I was obsessed with its incredibly dark vibe, and thought a lot about hyperbaric chambers and saturation diving.

Saturation divers use a technique that allows them to reduce the risk of decompression sickness (“the bends”) when they work at great ocean depths for long periods of time. The concept still freaks me out, but there are people with claustrophilia who actually desire the confinement of small spaces. This song reminds me of all of that, and my latent anxiety about the bottom of the ocean. I still haven’t learned how to scuba dive. Maybe someday I’ll face my fears.

2) “Street Spirit (Fade Out)”

“This machine will, will not communicate / These thoughts and the strain I am under / be a world child, form a circle / before we all go under / and fade out again and fade out again.”

Yorke has often referred to the impact of Spotify on musicians and the industry as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse.” When I first read that quote I laughed, as I occasionally do during Thom’s interviews. There’s an impishness to Yorke that I enjoy in live settings—and in his interactions with the press, there’s a side of him that I also see in myself. He delights in watching the establishment and industries we love straying away from old ideals and burning themselves down over and over, only to rise like the phoenix. “Street Spirit (Fade Out)” speaks to that intriguing conflict. Ed O’Brien’s arpeggiated guitar part uses an instrument created by the band’s guitar tech, Plank.

Yorke once called it the band’s “purest, saddest song.” It’s a spirit track for the downtrodden and brokenhearted, and it got me through multiple recessions and layoffs. “Street Spirit” was musically inspired by R.E.M. and Ben Okri’s 1991 novel The Famished Road. The book follows an abiku (“predestined to death”) spirit child living in an unnamed Nigerian city. I frequently thought about one of my ancestors on my mom’s side of the family, Giles Corey, when listening to the track. He was accused of being a warlock during the Salem witch trials, and his last words on Earth as he was pressed to death by large rocks was “more weight.” This song always felt like that heavy weight of a straining culture above you, and the spirit fading out afterwards.

1) “My Iron Lung”

“We scratch our eternal itch / Our twentieth century bitch / and we are grateful for our iron lung.”

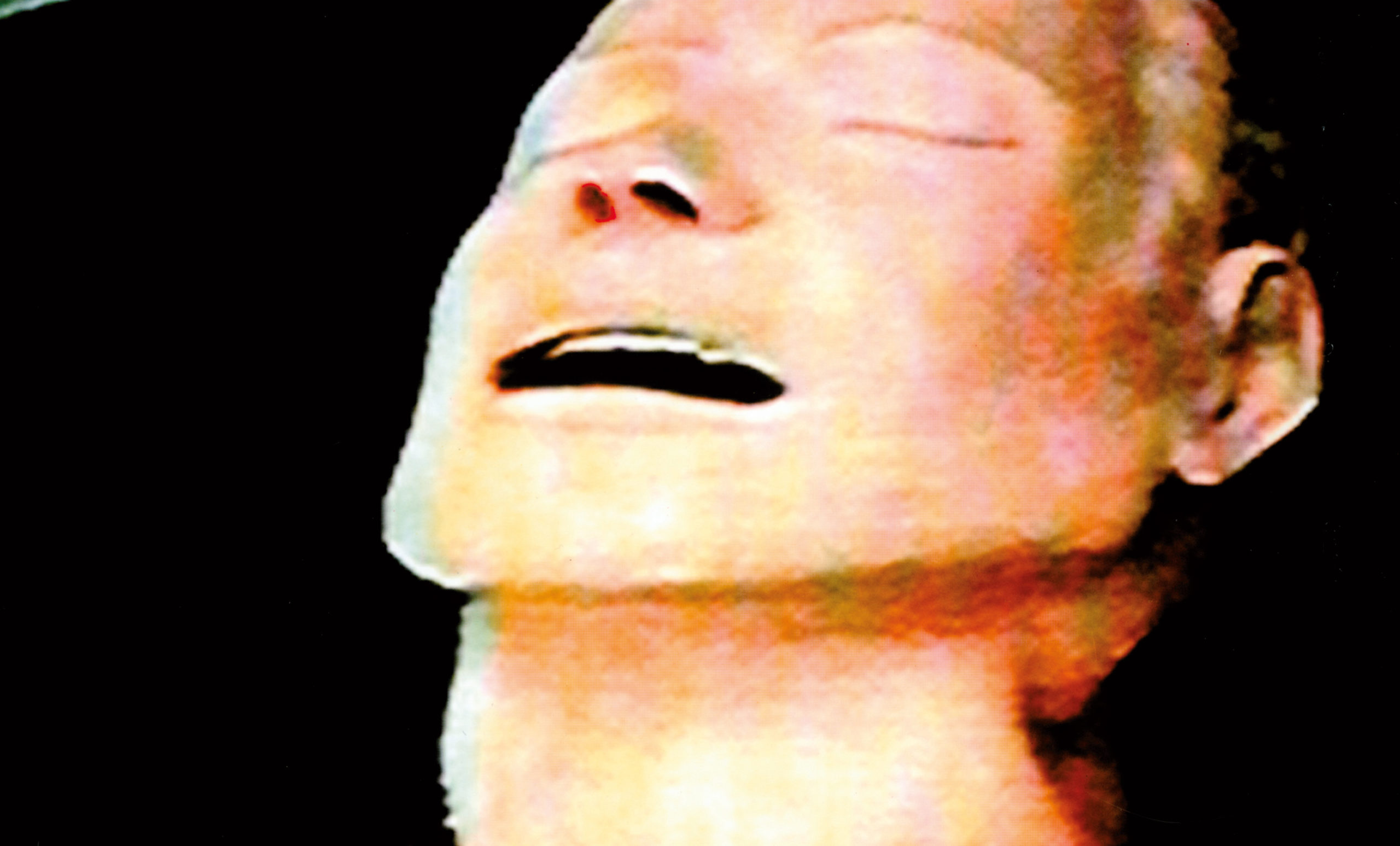

One of my all-time favorite stories from the making of The Bends centers on the sophomoric origins of the eerie album artwork. It’s actually just a grainy photograph taken from VHS footage of a CPR mannequin discovered at the University of Exeter. Radiohead were post-university twentysomethings at this point, fooling around while they created the artwork for the single “My Iron Lung.” A photograph of an actual iron lung wasn’t too appealing, so Stanley Donwood captured the now-iconic image by snapping a photo of a video playback with the CPR doll front and center, looking toward the heavens. Despite being lo-fi, it worked out—and Dorwood upped the ante with every Radiohead album cover after that.

“My Iron Lung” is the best song on the album for a variety of reasons, but for me it demarcates my transition into adulthood. I often turned it on to psych myself up before job interviews. It was Radiohead’s forceful reaction to 1993’s “Creep,” the young group’s hugely successful debut single off their mediocre debut LP, Pablo Honey. The cutting lyrics are self-referential and use an actual iron lung as a metaphor for the way “Creep” kept the band alive, but also crushed their true spirits as artists yearning for more adventurous sonic territories (“This is our new song / just like the last one / a total waste of time / my iron lung”).

This was a miniaturized detonation of an old song, whereas Kid A, years later, was an orchestrated dismantling of their discography thus far. The latter move opened a pathway to true reinvention every time they released something new. Radiohead will always be among my most cherished bands, helping to stave off my personal demons—and The Bends was the beginning of that relationship. My lizard brain thanks you. FL